- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- The Enigma That was Souza

- Progressive Art Group Show: The Moderns

- The Souza Magic

- M.F. Husain: Other Identities

- From All, One; And From One, All

- Tyeb Mehta

- Akbar Padamsee: The Shastra of Art

- Sensuous Preoccupations of V.S. Gaitonde

- Manishi Dey: The Elusive Bohemian

- Krishen Khanna: The Fauvist Progressive

- Ram Kumar: Artistic Intensity of an Ascetic

- The Unspoken Histories and Fragment: Bal Chhabda

- P. A. G. and the Role of the Critics

- Group 1890: An Antidote for the Progressives?

- The Subversive Modernist: K.K.Hebbar

- Challenging Conventional Perceptions of African Art

- 40 Striking Indian Sculptures at Peabody Essex Museum

- Tibetan Narrative Paintings at Rubin Museum

- Two New Galleries for the Art of Asia opens at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

- Raphael, Botticelli and Titian at the National Gallery of Australia

- The Economics of Patronization

- And Then There Was Zhang and Qi

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Random Strokes

- Yinka Shonibare: Lavishly Clothing the Somber History

- A Majestic “Africa”: El Anatsui's Wall Hangings

- The Idea of Art, Participation and Change in Pistoletto’s Work

- On Wings of Sculpted Fantasies

- The Odysseus Journey into Time in the Form of Art

- On Confirming the Aesthetic of Spectacle: Vidya Kamat at the Guild Mumbai

- Dhiraj Choudhury: Artist in Platinum Mode

- Emerging from the Womb of Consciousness

- Gary Hume - The Indifferent Owl at the White Cube, London

- Daum Nancy: A Brief History

- Experimenting with New Spatial Concepts – The Serpentine Gallery Pavilion Project

- A Rare Joie De Vivre!

- Art Events Kolkata-December 2011– January 2012

- Art Bengaluru

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Delhi Dias

- Musings from Chennai

- Preview, February, 2012- March, 2012

- In the News-January 2012

ART news & views

A Majestic “Africa”: El Anatsui's Wall Hangings

Issue No: 25 Month: 2 Year: 2012

by Sunanda K Sanyal

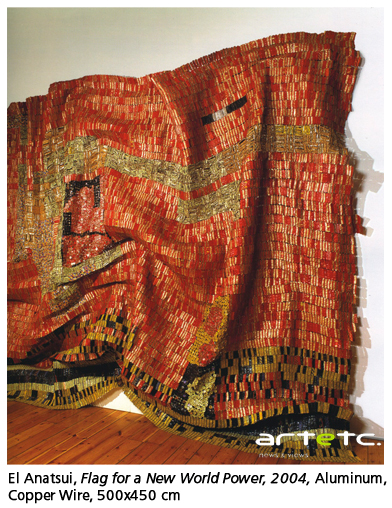

Displacement of objecthood has been one of the primary attributes of much of modern art in the latter half of the twentieth century. From the emergence of environments, installation and happenings in the 1960s, to earth art, conceptual art, and performance art of the subsequent decades, to digital art and new media of the recent years, the centrality of a tangible object rendered in a specific medium has been left behind as an exhausted modernist practice. The kind of meditative engagement required of such art has been rejected in favor of fragmented, dislocated experiences, where various mediating agencies have an active role in shaping the aesthetic of a work. Parallel to such radical shifts in art making, the identity politics of contemporary artists have also changed noticeably. The notion of the so-called national art scenes has gradually eroded into an internationalist discourse, which privileges hybrid identities of globally connected transnational artists who live, work and show at multiple international locations. And yet, the making of objects is far from obsolete, as is the creative enterprises of artists who, while well exposed in the international arena, are engaged in a relatively localized investigation of global identity. El Anatsui (b. 1944) is such an artist.

Displacement of objecthood has been one of the primary attributes of much of modern art in the latter half of the twentieth century. From the emergence of environments, installation and happenings in the 1960s, to earth art, conceptual art, and performance art of the subsequent decades, to digital art and new media of the recent years, the centrality of a tangible object rendered in a specific medium has been left behind as an exhausted modernist practice. The kind of meditative engagement required of such art has been rejected in favor of fragmented, dislocated experiences, where various mediating agencies have an active role in shaping the aesthetic of a work. Parallel to such radical shifts in art making, the identity politics of contemporary artists have also changed noticeably. The notion of the so-called national art scenes has gradually eroded into an internationalist discourse, which privileges hybrid identities of globally connected transnational artists who live, work and show at multiple international locations. And yet, the making of objects is far from obsolete, as is the creative enterprises of artists who, while well exposed in the international arena, are engaged in a relatively localized investigation of global identity. El Anatsui (b. 1944) is such an artist.

Born and raised in the Ewe culture of eastern Ghana, Anatsui has lived in Nigeria since 1975. He teaches at the art department of the University of Nsukka in southeastern Nigeria, the homeland of the Igbo. While he is widely traveled and recognized for his highly innovative work, Anatsui has declined opportunities to migrate to Europe or the United States. Instead, as a Ghanaian by birth, he has taken advantage of his immigrant status in a neighboring West African country – a culture in many ways very different from his own-- to continually reinvent endless resources for his creative research of the nuances of a fractured African identity in a globalizing world. Whereas the question of medium in the history of modern art has been primarily tied to formal, stylistic, technical and aesthetic factors, its relevance for Anatsui is deeply rooted in the cultural discourses of Ghana, Nigeria, and other West African nations and their diverse arrays of ethnicity. His versatile experiments of over four decades with clay and wood, for instance, testify to his inquisitive approach to these traditional West African mediums. In the current culture of globalism, where cross-cultural borrowings are informed by intercontinental dialogs, Anatsui's work might seem limited within the rhetorical framework of a stereotypical “Africa”. Such a myopic view, however, changes as one looks more closely at his creative strategies, such as his use of motifs from the Igbo body painting traditions of uli and nsibidi. In Anatsui's wood sculptures, these motifs from his adopted culture are either burnt into the wood surface as scar-like marks, or inscribed with a chain-saw. The results are complex personal narratives that override cultural nostalgia to forge a contemporary pictorial language out of traditional imagery. Ultimately, they neither speak for any specific African culture, nor do they attempt to legitimize an authentic Africa nurtured by the rest of the world. Rather, they offer a glimpse of the global vision of an artist who looks through a kaleidoscopic lens of cultural experience in contemporary Africa.

It is during the last decade that Anatsui has turned to an entirely new strategy of appropriation, producing objects that are as spectacular as they are art-critically significant. Diligently flattening hundreds of thousands of aluminum bottle caps of locally consumed liquors in Nigeria and painstakingly linking them with copper wire, he has made colorful, enormous, tapestry-like wall hangings that have marked a major turning point in his experiment with the relationship between medium and subject. Bricolage is a well-known African strategy of embracing modernity. Household cooking stoves made of hubs of automobile wheels and wicker lamps crafted out of discarded cans or light bulbs are abundant in any African marketplace; and Anatsui's work definitely addresses such practice. Yet his objects have no utility. Thus, to a mind unaccustomed to the creative enterprise of an African artist, they are likely to seem gimmicky – invested merely in the craft of their making– in their dazzling use of the detritus of modern life. It is only when one pays attention to the role of cultural memory and cross-cultural dialog across African cultures that one appreciates their creative strength. The immediate references here are two specific types of Ghanaian textile.

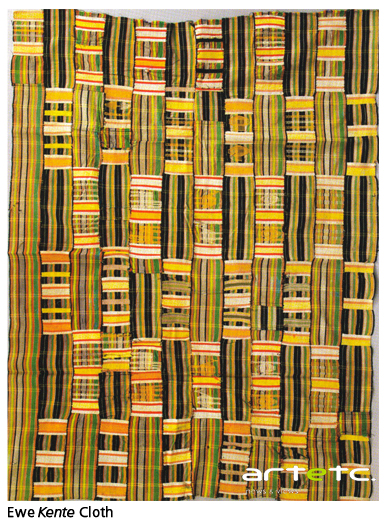

Anyone even cursorily familiar with Ghanaian culture knows the immense relevance of kente cloth in the construction of cultural identities in Ghana. Woven in colorful strips and stitched laterally to form a large square piece, kente is worn by men like a toga and by women in two or three pieces. What is more, as a royal cloth of the famed Akan kingdoms centered in Kumasi, it is widely used in religious rituals and funerals. Each of its patterns and color combinations has a distinct name and symbolism. The potential of this powerful pre-colonial signifier to articulate a new nationalist pride was fully exploited by Kwame Nkrumah, the first President of independent Ghana, who frequently wore kente in his public appearances. While the kente of Eweland in eastern Ghana, Anatui's birthplace, is different in color and style from the Akan cloth, it is equally important as a historically loaded cultural artifact. The other cloth that Anatsui's work alludes to is adinkra, a textile thinner and lighter than kente. Dyed in black and block-printed with specific patterns, it is used primarily on mourning occasions.

Anyone even cursorily familiar with Ghanaian culture knows the immense relevance of kente cloth in the construction of cultural identities in Ghana. Woven in colorful strips and stitched laterally to form a large square piece, kente is worn by men like a toga and by women in two or three pieces. What is more, as a royal cloth of the famed Akan kingdoms centered in Kumasi, it is widely used in religious rituals and funerals. Each of its patterns and color combinations has a distinct name and symbolism. The potential of this powerful pre-colonial signifier to articulate a new nationalist pride was fully exploited by Kwame Nkrumah, the first President of independent Ghana, who frequently wore kente in his public appearances. While the kente of Eweland in eastern Ghana, Anatui's birthplace, is different in color and style from the Akan cloth, it is equally important as a historically loaded cultural artifact. The other cloth that Anatsui's work alludes to is adinkra, a textile thinner and lighter than kente. Dyed in black and block-printed with specific patterns, it is used primarily on mourning occasions.

Seen from a distance, Anatsui's wall hangings indeed demonstrate the flexibility, flow, and shimmering surface of textile, their patterns often reminiscent of kente or adinkra. Like textile, the folds and contours are formed differently each time they are installed. Yet they are far from metal replicas of kente or adinkra cloth, as none of them precisely emulates any patterns from either fabric. Instead, what from afar looks like spectacular waves of shimmering colors and complicated textures turn out, on closer inspection, to be a dense blanket made of flattened metal, with pieces of the same brand, texture and color meticulously grouped together to provide the unity of visual effect over specific areas of the surface. And herein is the irony of these wall pieces: mere garbage of modern life found in one West African country is transformed to recall one of the most revered markers of cultural authenticity (kente or adinkra) of another. To Anatsui, discarded bottle caps symbolize mass migration and consumption in a globalizing Africa; as such, they are surrogates for the consumers themselves. Rigorously flattened, and with the links of copper wire clearly visible, the quotidian objects with their familiar brand logos (carrying the baggage of a capitalist market culture with them) constitute a dynamic medium for articulating the constructed nature of African cultural identity. In other words, using the Ghanaian textiles as points of reference, the objects offer themselves as mnemonic devices; markers that on the one hand acknowledge the human desire for cultural authenticity, while on the other hand subvert it by baring the fact that identity, like art, is tentatively made up of disparate elements, both local and global. This cross-cultural insight, where the materials employed are both palpably present, yet rise above their sheer materiality, prevents the body of work from being simply obsessive craftwork.

So how does one categorize Anatsui's objects? Where do they belong in the pantheon of painting and sculpture? As Robert Storr cautions, citing hasty analogies from modern western art might be tragically misleading1. The aggressive role of colors on the surfaces, for example, unequivocally breaks new grounds in abstraction; yet they are the readymade colors of the manufactured bottle caps, which have been methodically arranged, not painted, by the artist. Likewise, the gestural effect produced by the folds under specific lighting conditions is not made up of the artist's marks recorded on the surface in the conventional sense. Furthermore, because the readymade components used to construct the objects collectively negate their own presence when seen from a distance, this loss of literalness, even if momentary, sets them apart from minimalist painting or sculpture. Could we, then, call them pictorial sculptures, as Storr tentatively suggests? Perhaps.

So how does one categorize Anatsui's objects? Where do they belong in the pantheon of painting and sculpture? As Robert Storr cautions, citing hasty analogies from modern western art might be tragically misleading1. The aggressive role of colors on the surfaces, for example, unequivocally breaks new grounds in abstraction; yet they are the readymade colors of the manufactured bottle caps, which have been methodically arranged, not painted, by the artist. Likewise, the gestural effect produced by the folds under specific lighting conditions is not made up of the artist's marks recorded on the surface in the conventional sense. Furthermore, because the readymade components used to construct the objects collectively negate their own presence when seen from a distance, this loss of literalness, even if momentary, sets them apart from minimalist painting or sculpture. Could we, then, call them pictorial sculptures, as Storr tentatively suggests? Perhaps.

The more important question, however, is whether such a categorization is necessary at all. In one's anxiety to ponder such a question, doesn't one fall prey to the old modernist quibble over the specificity and sanctity of medium? Rather, the imposing objecthood of the objects, contradicted by their liminal status between mediums, is precisely what seems to be the source of their power. Scavenging modern detritus once led to the use of found objects in sculptural constructions in America and Europe; and they deliberately appeared aggressive and raw to function effectively in the process of signification. In this case, that legacy of found objects finds a new identity; garbage is made to look beautiful, yet accomplishes an even more complicated task of underscoring the different but equally legitimate position that El Anatsui occupies in the discourse of contemporary art. Call them pictorial sculpture, objectified painting, metal tapestries, wall hangings, objects, or simply “things”, if you will; but in all their ambiguity, they make notable contributions to the dialog between two- and three-dimensionality, between picture and object, which began decades ago. What is more, they forcefully argue the global vision of an African artist, whose cross-cultural borrowings within Africa are capable of addressing discourses of art and identity beyond that continent.

Reference

1. Storr, Robert, "The Shifting Shapes of Things to Come". El Anatsui: When I Last Wrote to You About Africa. New York: Museum of African Art, 2011: 51-62.