- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- The Enigma That was Souza

- Progressive Art Group Show: The Moderns

- The Souza Magic

- M.F. Husain: Other Identities

- From All, One; And From One, All

- Tyeb Mehta

- Akbar Padamsee: The Shastra of Art

- Sensuous Preoccupations of V.S. Gaitonde

- Manishi Dey: The Elusive Bohemian

- Krishen Khanna: The Fauvist Progressive

- Ram Kumar: Artistic Intensity of an Ascetic

- The Unspoken Histories and Fragment: Bal Chhabda

- P. A. G. and the Role of the Critics

- Group 1890: An Antidote for the Progressives?

- The Subversive Modernist: K.K.Hebbar

- Challenging Conventional Perceptions of African Art

- 40 Striking Indian Sculptures at Peabody Essex Museum

- Tibetan Narrative Paintings at Rubin Museum

- Two New Galleries for the Art of Asia opens at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

- Raphael, Botticelli and Titian at the National Gallery of Australia

- The Economics of Patronization

- And Then There Was Zhang and Qi

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Random Strokes

- Yinka Shonibare: Lavishly Clothing the Somber History

- A Majestic “Africa”: El Anatsui's Wall Hangings

- The Idea of Art, Participation and Change in Pistoletto’s Work

- On Wings of Sculpted Fantasies

- The Odysseus Journey into Time in the Form of Art

- On Confirming the Aesthetic of Spectacle: Vidya Kamat at the Guild Mumbai

- Dhiraj Choudhury: Artist in Platinum Mode

- Emerging from the Womb of Consciousness

- Gary Hume - The Indifferent Owl at the White Cube, London

- Daum Nancy: A Brief History

- Experimenting with New Spatial Concepts – The Serpentine Gallery Pavilion Project

- A Rare Joie De Vivre!

- Art Events Kolkata-December 2011– January 2012

- Art Bengaluru

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Delhi Dias

- Musings from Chennai

- Preview, February, 2012- March, 2012

- In the News-January 2012

ART news & views

The Idea of Art, Participation and Change in Pistoletto’s Work

Issue No: 25 Month: 2 Year: 2012

by Leandre D'Souza and Claudio Maffioletti

Michelangelo Pistoletto is one of the most influential living Italian artists and a central figure of the Arte Povera movement. A term coined in 1967 by critic and curator Germano Celant Arte Povera alludes to “poor research, intent upon the identification of the individual in his actions [and] in his behaviour, thus eliminating all separation between these two levels of existence”. This approach is opposed to a rich attitude “connected to the enormous instrumental and informational possibilities that the system offers”, which compels artists to produce “fine commercial merchandise”1 .

A prominent feature of Pistoletto’s artistic research is the dissolution of the individual self into the community he belongs to. This is particularly evident in his series Mirrors Paintings (Quadri Specchianti) and his Minus Objects (Oggetti in Meno), and is framed into a specific period and place: the city of Turin, the breeding ground for the Italian “economic miracle” of the ‘50s which degenerated into social and political crisis during the second half of the ’60s, and shockingly climaxed into terroristic violence in 1975.

The Mirror Paintings (Quadri Specchianti)

Influenced by both the dolorous figures of Francis Bacon and the evanescent textures of Jean Fautrier’s portraits, Pistoletto’s early self-portraits concentrate on the anonymity of the individual self and on the sense of incompleteness which permeates the space around the subject. At one point, the paint is replaced by stainless steel and the background becomes completely reflective, thus bringing the context inside the artwork itself, incorporating the features of the contiguous space and the bodies of standing viewers. Initially characterized by the presence of isolated and monochromatic figures, the Mirror Paintings evolve to host colorful groups of people and couples. Thus the work forever captures and appropriates real space within the representational one. As a mirror reflects anything put in front of it, it also encapsulates and frames the notion of possibility, and coaxes the viewer to transform himself/herself into a transient participant, a transitory actor. “My […] works are a testimony of my need to live and act according to […] the non-repeatability of every present instant, every place and therefore every action”2. The Mirror Paintings became quickly successful, and New York-based Italian gallerist Leo Castelli solicited Pistoletto to produce more works and to start a new career in the US as part of “his” group of artists. But Pistoletto refused.

Minus Objects (Oggetti in Meno)

With it, he refused to acknowledge an idea of art as a stable system governed by market conditions of artistic production and fruition. He preferred to assert “the need to operate independently and to imagine […] a community free from hierarchies and centralizing entities.”3

Since then, a new research started: the series Oggetti in Meno provided the framework and setting for poetry recitals, film viewings, discussions organized in Pistoletto’s studio and also during performances by the theatrical group Lo Zoo.

Struttura per Parlare in Piedi (Structure to speak while standing, 1965-66) combines welded and painted iron pipe offering support for people to lean on while conversing. The pipe forms a stage and invites people to gather around and chat. Mappamondo (world map, 1966-68) is a giant ball made of newspapers taken into the streets for a walk titled Scultura da Passeggio (Walking Sculpture). In 1965, he carved from one piece of wood, a frame popularly known as Quadro da Pranzo (Lunch Painting), which forms two right-angled seats and a table. The frame extends itself enough to allow participants to actually have lunch while they sit within the image.

Scultura Lignea (Wooden Sculpture, 1965-66) juxtaposes dichotomous materials – wood and plexiglass – one worn and the other brand new. An antique, densely chafed wooden sculpture of the Madonna is placed inside a shiny, orange Plexiglas container which covers only her lower half. The virginal, historical figure protruding from the plastic constructs a dialogue on what art means and what art can do. It tries to make the viewer aware of his/her own present positioning which is as important as the past that has been carefully preserved.

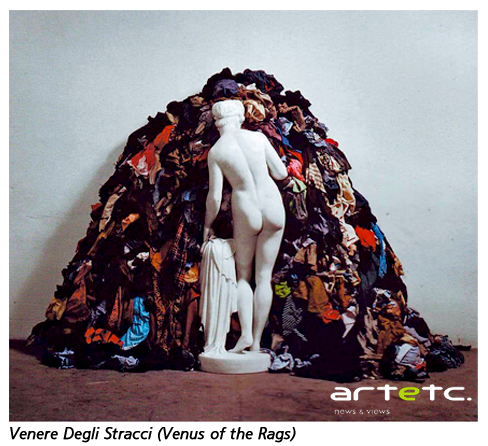

Venere Degli Stracci (Venus of the rags, 1967) has a marble statue of the nude Venus posing in front of a pile of rags. Venus is overwhelmed by refuse – cloth that carries no meaning but in its entirety, communicates a need when amassed together and placed in front of an iconic classical sculpture. Past and future cross over in the present moment.

Venere Degli Stracci (Venus of the rags, 1967) has a marble statue of the nude Venus posing in front of a pile of rags. Venus is overwhelmed by refuse – cloth that carries no meaning but in its entirety, communicates a need when amassed together and placed in front of an iconic classical sculpture. Past and future cross over in the present moment.

Besides the playfulness of these works, Pistoletto calls his audience to act. In their incongruity, illogical sequence and fragmented nature, the works present themselves as subtractions from infinite possibilities, hence the title of the series. They also introduce a shift in the perception of the role of the artist, no longer an author privately creating artworks according to a particular sense and style, but rather an agent initiating a process and an exchange with other beings. As Pistoletto stated referring to his experience with Lo Zoo “we no longer work for viewers; we ourselves are actors and viewers, makers and consumers. Among those of us who are able to work together there is a direct, clear, perceptive and instantaneous relationship…. When you see, hear and smell a piece we play out together […] what you think you understand will be just the skin, the envelope, but you will never know what happened until you become actors and viewers on this side of the bars”.4

Engaging with Pistoletto’s works is like falling into the wonderland of a crazed ventriloquist who mesmerizes his viewer both physically and metaphysically. What role we decide to enact in this improvisatory spectrum of activities, what we will give or take is entirely dependent on us. As painter, performer, poet, he merges multifarious art forms and disciplines, and through this binding tries to efface the line separating the exhibition space to the outside world. By altering the inside space into a maze of experimentation, he tries to connect his work with life and its different possibilities, be they social, political, historical, cultural or scientific.5

In his mirror works, we see ourselves – fragile just like the stainless steel sheet that forces us to look closely. With his Minus Objects we face a series of works each with its own identity, existing like unconnected events – a conundrum, pieced together by the viewer’s social activation.

With these works Pistoletto brings together a cross-disciplinary spectrum, which takes art to the public, encouraging participation and action. Without the audience the works would not exist. He alluringly ropes them into a bizarre pandemonium, a return to childhood or a loosening of societal chains. Like a lightening flash, he winds the viewer’s ‘liberation mechanism’ enticing the ‘caged’ animal to free itself.

Pistoletto investigates processes that concentrate on human experience. Through infusions and transmutations of matter, he conjures up works that magically open, inviting perceptual interactions with metaphysical elements – energy, magnetism, gravity. By formulating new ways to perceive material and to interact with the natural world, the artist awakens the audience, becoming the medium through which ordinary objects encourage critical thinking and question the individual’s perception of self and self in relation to others.

Unlike the avant-gardes, Dada, the Situationists and Fluxus, however, Pistoletto’s work does not intend to bring art into life, but rather to investigate the tension between the two, recognizing the barrier between the artistic and the existential dimension. As Pistoletto himself puts it, “Art is like scissors; there are two paradigms: on one side there’s orthodoxy, on the other side, heterodoxy. The first one is art for its own sake. The second one is a type of art which is not afraid of opening up and interacting with the world. I’m developing these two paradigms because I see them as complementary”.6

Reference

1. G.Celant, Arte Povera: Appunti per una guerriglia’, in Flash Art, n. 5, Nov/Dec, pg. 3, 1967

2. Michelangelo Pistoletto, Un artista in meno, Hopefulmonster, Torino 1989, p. 12

3. G. Guercio, Una comunità del non-tutto, in Michelangelo Pistoletto, Da uno a molti – 1956-1974, Exhibition Catalogue, MAXXI, Rome 2011.

4. Michelangelo Pistoletto, “Lo Zoo,” inTeatro, no. 1, Milan 1969, 16

5. Gareth Harris, “The rich legacy of arte povera,” Art Basel Miami Beach daily edition, from www.theartnewspaper.com, 1 Dec 2010

6. G. Politi, Inside and Outside the Mirror, interview with Michelangelo Pistoletto, Flash Art n.271 March – April 2010