- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

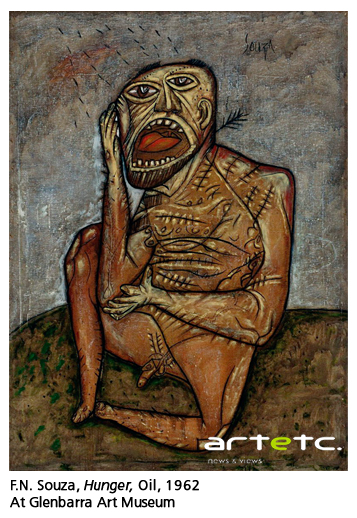

- The Enigma That was Souza

- Progressive Art Group Show: The Moderns

- The Souza Magic

- M.F. Husain: Other Identities

- From All, One; And From One, All

- Tyeb Mehta

- Akbar Padamsee: The Shastra of Art

- Sensuous Preoccupations of V.S. Gaitonde

- Manishi Dey: The Elusive Bohemian

- Krishen Khanna: The Fauvist Progressive

- Ram Kumar: Artistic Intensity of an Ascetic

- The Unspoken Histories and Fragment: Bal Chhabda

- P. A. G. and the Role of the Critics

- Group 1890: An Antidote for the Progressives?

- The Subversive Modernist: K.K.Hebbar

- Challenging Conventional Perceptions of African Art

- 40 Striking Indian Sculptures at Peabody Essex Museum

- Tibetan Narrative Paintings at Rubin Museum

- Two New Galleries for the Art of Asia opens at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

- Raphael, Botticelli and Titian at the National Gallery of Australia

- The Economics of Patronization

- And Then There Was Zhang and Qi

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Random Strokes

- Yinka Shonibare: Lavishly Clothing the Somber History

- A Majestic “Africa”: El Anatsui's Wall Hangings

- The Idea of Art, Participation and Change in Pistoletto’s Work

- On Wings of Sculpted Fantasies

- The Odysseus Journey into Time in the Form of Art

- On Confirming the Aesthetic of Spectacle: Vidya Kamat at the Guild Mumbai

- Dhiraj Choudhury: Artist in Platinum Mode

- Emerging from the Womb of Consciousness

- Gary Hume - The Indifferent Owl at the White Cube, London

- Daum Nancy: A Brief History

- Experimenting with New Spatial Concepts – The Serpentine Gallery Pavilion Project

- A Rare Joie De Vivre!

- Art Events Kolkata-December 2011– January 2012

- Art Bengaluru

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Delhi Dias

- Musings from Chennai

- Preview, February, 2012- March, 2012

- In the News-January 2012

ART news & views

The Economics of Patronization

Issue No: 25 Month: 2 Year: 2012

Art Market

Market Monitor

by Art Bug

If you are an art enthusiast you might know the link between W. Langhammer, Rudy Von Leyden, Emanuel Schlesinger, Kito de Boer, Charles Herwitz and S.H Raza, F. N. Souza, M. F Husain, Tyeb Mehta, V. S Gaitonde. The Bombay Progressive Artists Group brought these two different sects of people together.

While the second list are the names of the most prominent figures of this school of contemporary Indian art, the first is the list of names of those without whom the second list would probably never have been known to the world. Langhammer, Leyden and especially Schlesinger had been the most ardent patrons of the group of young artists who formed the Bombay Progressive Artists Group in 1947. It was under their influence that the likes of Husain, Raza and Souza came in close contact with various European expressions of art—both in terms technique as well as thought.

Kito de Boer and Charles Herwitz came into the scene later, but not as late when these contemporary masters of Indian art had started burning the auction floors as they are doing now.

As Raza had remembered, “Professor Langhammer took to me very kindly and not only gave his studio for me to work where he stayed but also helped me with his views on the kind of work I was doing then. He used to put in front of me paintings by Raphael, El Greco, Monet and Cezanne, paintings of the Persian, Rajput and Mughal miniatures and he would say, ‘Look at these paintings and tell me what is happening there.’ It was a tough job but it was an eminent awareness of form which started developing in me which I started to follow in time to come.”

But how and why did the patrons get so involved with the Progressives?

As the story goes, the likes of Schlesinger got associated with the likes of Raza and Souza even before they had actually formed the Group. They had, in short, the 'vision'. For example Schlesinger, a former Austrian Jew who had fled Germany, arrived in India in 1940. A pharmacist by profession, he established the Indo-Pharma Company and was one of the main drivers along with Holck-Larsen of Larsen and Toubro of the corporate culture of buying art in India. Schlesinger, whom Husain described as ‘a father figure’ would not only commission them to paint but would also have them reproduced in the calendar of his company.

Frankly speaking, an examination of the canvases of Raza, Souza and Husain in their salad days were quite different from what they started producing later. Raza, for example, was still far from his trademark geometric canvases representing his inner thoughts—an example of which made him the highest priced Indian artist at an international auction to date. In short, the Progressives were still to develop their own signature styles, but their patrons had already, way back in the late forties and early fifties, identified their potentials and being exposed to the then-contemporary trends in European and American art, actively guided them in their forms and styles.

At the same time, they were also gathering the works of these artists. And at that point of time, they were gathering them for what can best be said as ‘peanuts’ in terms of price. A thousand Indian rupees, at that time was huge for strugglers like Husain, but the price these canvases are capable of fetching now are astonishing.

The point of this whole discussion thus far is simple—the Progressives, despite their artistic and to some extent business acumen—had also been the result of the ‘vision’ of their patrons, who of course supported them but also in one sense invested in what would be good business ventures in the future. And it is showing.

In 2010, even after the great surge of 2008-09 in the revival of Indian contemporary paintings on international auction floors, especially at a time of worldwide economic depression, Indian contemporaries like Raza, Souza, Gaitonde, Husain and Mehta held forth.

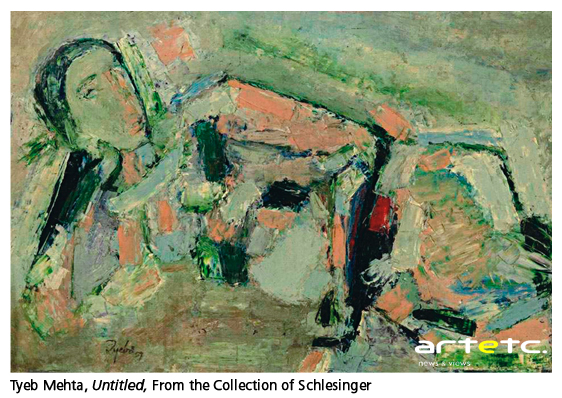

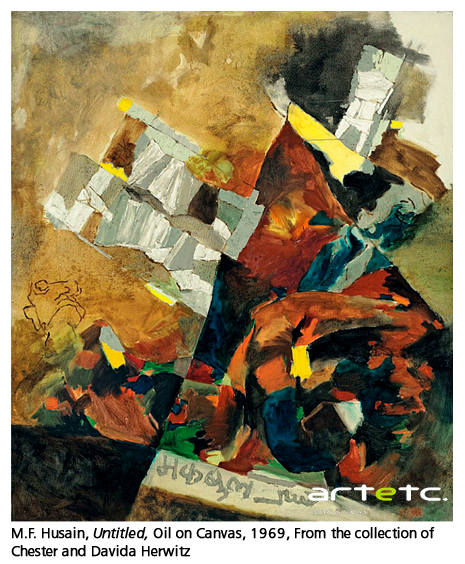

For example, Emmanuel Schlesinger who lived in Bombay from 1939 till his death in 1968 was a patron and major influence over the Progressives. His collection was offered at the Sotheby's Indian and South East Asian Art held on 24 March 2010. Among the many artists he knew and worked with was Tyeb Mehta whose Untitled, estimated at $100/150,000 was the highlight of the collection on sale. The said work eventually sold for $566,000, almost five times the higher estimate. The highlight of the Sotheby’s sale however was a 1955 Untitled by Husain which achieved the highest price of the day when it fetched $1,058,500, over five times the estimate. In a rare instance of auction floor success, Sotheby’s was able to sale the whole of The Emanuel Schlesinger Collection at an astonishing $ 921,650 against an estimate of $237/352,000.

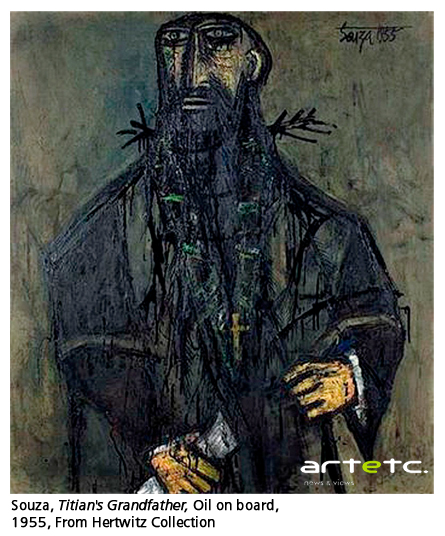

Mere figures are not the point here. The global recession and the speculative nature of the art market (especially the contemporary Indian art market) which had artificially jacked up the prices for many works during 2008-09, touted to be the best years of Indian art till now, had forced the auction houses in 2010 to revise their pre-sale estimates to a more moderate level. Even on those terms, a pre-sale estimate of $237/352,000 for a private collection was not quite humble, especially considering the fact that Schlesinger had, after his death, offered to give away his collection to the Prince of Wales Museum which was rejected on grounds of the works being ‘imitative’. Yet, the highest estimate was overturned by almost three times the price. That only goes on to establish the vision of Schlesinger as a collector.

Mere figures are not the point here. The global recession and the speculative nature of the art market (especially the contemporary Indian art market) which had artificially jacked up the prices for many works during 2008-09, touted to be the best years of Indian art till now, had forced the auction houses in 2010 to revise their pre-sale estimates to a more moderate level. Even on those terms, a pre-sale estimate of $237/352,000 for a private collection was not quite humble, especially considering the fact that Schlesinger had, after his death, offered to give away his collection to the Prince of Wales Museum which was rejected on grounds of the works being ‘imitative’. Yet, the highest estimate was overturned by almost three times the price. That only goes on to establish the vision of Schlesinger as a collector.

The story actually had started as early as 1995. Holly Brackenbury, deputy director of Sotheby’s for Islamic and Indian Art, in an interview to Livemint.com commented, "Sotheby’s held the first-ever auction of modern Indian art in 1995. It was a groundbreaking sale of the Herwitz Collection of Indian art in New York for a total of $856,000. Those sales really put Indian art on the international map." Brackenburry went on to add that, "The interest of bluechip collectors such as Charles Saatchi and Frank Cohen, who are the tastemakers for the art market, was an important factor" in the continuing interest in Indian Contemporary Artists.

This in one stroke shows the vision of collectors like Charles Herwitz .

And it is not just about seasoned European and American collectors. As Anindita Ghose wrote in her article 'A Decade in Indian Art' (Livemint.com), "... this was the decade when the creature called the Indian art collector came into being. Up until this decade, serious collectors of Indian art such as Emmanuel Schlesinger and Charles Herwitz had been European or American." But now, there's a Harsh Goenka and a Anupam Poddar, whose names are uttered in the same breath.

But what exactly prompts collectors of Progressives to acquire such artworks? In 2010, Kito De Boer wrote a small article for the Economic Times on January 24, where the middle-east director of Mackinsey & Company tried to explain the passion which extols him to collect contemporary Indian art. He wrote, “We collect Indian art from the early Bengal period to the late 20th century, tracing the arc of India's history—from the colonial period through the modern independent era. This gives our collection artistic and historic breadth.. We purchased our first paintings on impulse. These were an emotional response, reflecting our excitement at the vibrancy and energy of India's culture. Since then, collecting India's art has become an obsession. It has come to shape our lives.

Today our collection has over 700 works of Indian art. Far too many to display! The moment you run out of wall space and yet continue to acquire, is the time to admit that obsession has become addiction. …Every day we sit in the company of some of India's greatest figures: Gaitonde, Souza, Husain, Chittaprosad, Pyne, Broota, Raza and many more. Every day they whisper to us. They reveal the genius that is India. Surrounded by our collection we are wrapped in the energy of the finest souls of a great civilisation and that is a privilege beyond economic logic.”

A moving article no doubt, which tries to establish the fact that collecting is a privilege beyond ‘economic logic’ but the operative sentiment that hides behind the fine print is – “Far too many to display! The moment you run out of wall space and yet continue to acquire, is the time to admit that obsession has become addiction.” In the winter of 2006, John Elliot, writing on the market of Indian Contemporary Art in The Royal Academy of Arts reported De Boer's sentiment at that point of time. "De Boer believes that in the contemporary art market ‘there has been a considerable amount of manipulation by dealers’. Some younger artists are cashing in on the boom with quick compositions, often dictated by the market." De Boer, it seems still believes in the same sentiments and holds on to his collection for an opportune moment. This observation may be significant but when it comes to Progressives, it is actually the other way round. The stature of these artists contribute to the functioning of the market to a large extent. For example, Sprinkling Horses by M. F Husain sold for $1.14 million at an auction last year after his death. This has been one of the highest prices fetched by a Husain painting and the Wall Street Journal reported on September 14, 2011, that it is “a positive sign for the Indian art market."

The estimate for 'Sprinkling Horses,' was not made public and it was one of 13 paintings by Husain that were presented at Christie’s auction of South Asian modern and contemporary art in New York. All were sold, for a total of $4.2 million. Among his other paintings that were sold was Yatra (1955). It sold for over $920,00, more than twice the average sales estimate. What is significant is that all of his other works either beat or met estimates.

The report goes on to add, “Christie’s is the first of three auctions of Indian art in quick succession offering a wide selection of works by Mr. Husain. These are the first major sales to take place since his death, an important market test for his artistic production. The results at Christie’s raise expectations for the upcoming auctions at Sotheby’s and Saffronart."

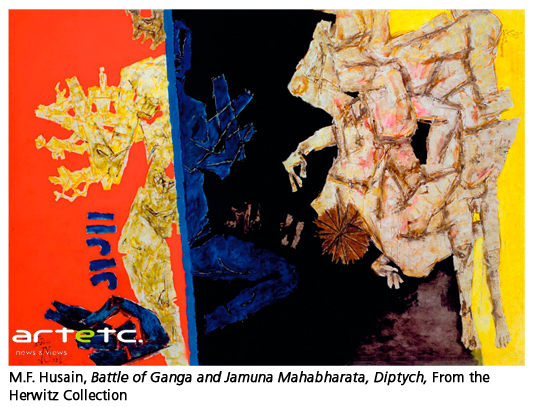

Husain's Shafdar Hashmi was sold for $1.1 million in 2008 at Emami Chisel Art – at the time the highest sum ever paid for a work of modern Indian art. More recently, in 2008, his Battle of Ganga and Jamuna: Mahabharata, a diptych sold for $1.6 million.

Husain's Shafdar Hashmi was sold for $1.1 million in 2008 at Emami Chisel Art – at the time the highest sum ever paid for a work of modern Indian art. More recently, in 2008, his Battle of Ganga and Jamuna: Mahabharata, a diptych sold for $1.6 million.

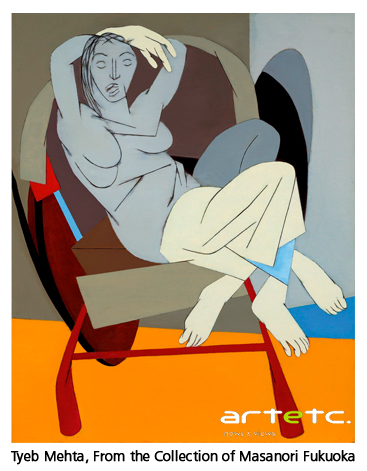

If Husain breaks his own records time and again, so do the other Progressives. Husain still remains behind S.H. Raza and Tyeb Mehta. Raza’s “Saurashtra,” sold for $3.5 million in 2010— and this record for the highest priced Indian canvas holds even after two years. On the other hand, Tyeb Mehta, although far less prolific has periodically broken the one-million-dollar mark. His diptych Bulls, which sold for $2.8 million in March 2011, was seen as a sign that the Indian art market was on the way to recovery from the economic downturn. At the Christie’s auction where Husain's Sprinkling Horses crossed the million dollar mark, Mehta’s Untitled (Man vs. Horse), and oil on canvas, sold for $600,000. This again was higher than estimated.

This goes on to illustrate the ‘vision’ of the patrons that we have been discussing. When to hold on and when to let go. The Schlesinger collection came on auction almost forty years later and reaped more than satisfactory results. As a matter of fact, investing in art is also a matter of risk, where the gestation period may be huge, as also the brand build-up of the artist concerned.

And the markets of the Progressives are increasing by the day too. Several prestigious museums worldwide display Indian art now. The trend is largely driven by huge curiosity among attentive art admirers to explore India’s amazing transformation from a agrarian economy to an economic superpower with complex socio-political connotations as seen through the eyes of leading artists. And this transitory aspect is best portrayed by the Bombay Progressives, who had started before India gaining Independence and has seen her grow with them. Masanori Fukuoka, an eminent collector, built the Glenbarra Art Museum in Japan to display his collection of Indian contemporary art. The museum has a rich collection featuring masters and contemporaries like Akbar Padamsee, Arpita Singh, F.N. Souza, Ganesh Pyne, Jogen Chowdhury, J. Swaminathan, M.F. Husain, Nasreen Mohamedi, Ram Kumar, Tyeb Mehta, Ved Nayar, Kartick Pyne, V.S. Gaitonde, Atul Dodiya, Krishen Khanna, Laxma Goud, Manjit Bawa, Prabhakar Kolte, and Prabhakar Barwe. A look at the list of names will clearly show that in a prestigious museum like Glenbarra, the Bombay Progressives clearly hold sway. And in regard to his collection, Fukuoka had once remarked, "Above all there is a sense of creative adventure that reaches out to something beyond the image, through the image - be it figurative or abstract... This, I feel, is what captivated me - the glimpse of a window in the image, opening to a space beyond." It almost reflects the sentiments of De Boer and is a clear proof how the Progressives still hold sway in the field of contemporary Indian art. It is also proof of the 'vision' of the first five patrons of the Progressives.

And the markets of the Progressives are increasing by the day too. Several prestigious museums worldwide display Indian art now. The trend is largely driven by huge curiosity among attentive art admirers to explore India’s amazing transformation from a agrarian economy to an economic superpower with complex socio-political connotations as seen through the eyes of leading artists. And this transitory aspect is best portrayed by the Bombay Progressives, who had started before India gaining Independence and has seen her grow with them. Masanori Fukuoka, an eminent collector, built the Glenbarra Art Museum in Japan to display his collection of Indian contemporary art. The museum has a rich collection featuring masters and contemporaries like Akbar Padamsee, Arpita Singh, F.N. Souza, Ganesh Pyne, Jogen Chowdhury, J. Swaminathan, M.F. Husain, Nasreen Mohamedi, Ram Kumar, Tyeb Mehta, Ved Nayar, Kartick Pyne, V.S. Gaitonde, Atul Dodiya, Krishen Khanna, Laxma Goud, Manjit Bawa, Prabhakar Kolte, and Prabhakar Barwe. A look at the list of names will clearly show that in a prestigious museum like Glenbarra, the Bombay Progressives clearly hold sway. And in regard to his collection, Fukuoka had once remarked, "Above all there is a sense of creative adventure that reaches out to something beyond the image, through the image - be it figurative or abstract... This, I feel, is what captivated me - the glimpse of a window in the image, opening to a space beyond." It almost reflects the sentiments of De Boer and is a clear proof how the Progressives still hold sway in the field of contemporary Indian art. It is also proof of the 'vision' of the first five patrons of the Progressives.