- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- The Enigma That was Souza

- Progressive Art Group Show: The Moderns

- The Souza Magic

- M.F. Husain: Other Identities

- From All, One; And From One, All

- Tyeb Mehta

- Akbar Padamsee: The Shastra of Art

- Sensuous Preoccupations of V.S. Gaitonde

- Manishi Dey: The Elusive Bohemian

- Krishen Khanna: The Fauvist Progressive

- Ram Kumar: Artistic Intensity of an Ascetic

- The Unspoken Histories and Fragment: Bal Chhabda

- P. A. G. and the Role of the Critics

- Group 1890: An Antidote for the Progressives?

- The Subversive Modernist: K.K.Hebbar

- Challenging Conventional Perceptions of African Art

- 40 Striking Indian Sculptures at Peabody Essex Museum

- Tibetan Narrative Paintings at Rubin Museum

- Two New Galleries for the Art of Asia opens at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

- Raphael, Botticelli and Titian at the National Gallery of Australia

- The Economics of Patronization

- And Then There Was Zhang and Qi

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Random Strokes

- Yinka Shonibare: Lavishly Clothing the Somber History

- A Majestic “Africa”: El Anatsui's Wall Hangings

- The Idea of Art, Participation and Change in Pistoletto’s Work

- On Wings of Sculpted Fantasies

- The Odysseus Journey into Time in the Form of Art

- On Confirming the Aesthetic of Spectacle: Vidya Kamat at the Guild Mumbai

- Dhiraj Choudhury: Artist in Platinum Mode

- Emerging from the Womb of Consciousness

- Gary Hume - The Indifferent Owl at the White Cube, London

- Daum Nancy: A Brief History

- Experimenting with New Spatial Concepts – The Serpentine Gallery Pavilion Project

- A Rare Joie De Vivre!

- Art Events Kolkata-December 2011– January 2012

- Art Bengaluru

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Delhi Dias

- Musings from Chennai

- Preview, February, 2012- March, 2012

- In the News-January 2012

ART news & views

Manishi Dey: The Elusive Bohemian

Issue No: 25 Month: 2 Year: 2012

by Satyasri Ukil

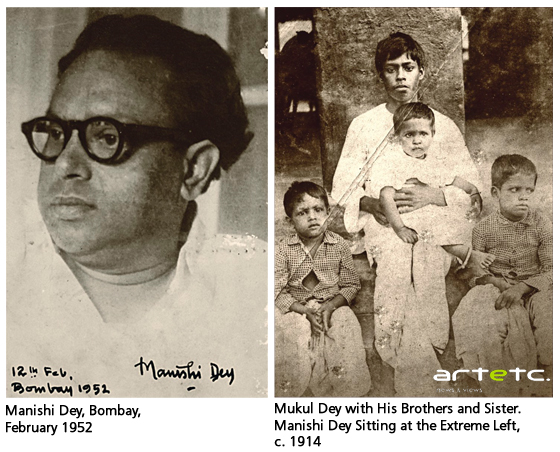

My earliest recollection of Manishi Dey’s painting is an exquisite water-color of a blue kingfisher, which once hung at a corner of my grandfather’s studio at Santiniketan. The old man often contemplated upon it for a longtime and would whisper softly that Manishi had a very sensitive brush. Those were the days of mid-1960s. I knew that Manishi was my grandfather’s younger brother. Unfortunately, none of his brothers or sisters left any reminiscences about Manishi Dey who was undoubtedly one most gifted artist in their own generation. Here a sort of a profile of the artist is pieced together from old photographs, multiple correspondence and news clippings of Manishi, which are preserved in Mukul Dey Archives collection. In the outset I must also mention that though I have been invited to profile Manishi Dey as a member of Progressive Artists Group of Bombay, essentially we are here to deal with an artist who remained a wanderer throughout his life. A wanderer, who shifted not only his geographical locations frequently, but changed his visual idioms as easily as often.

Manishi Dey (1909—1966), originally named Bijoy Chandra, was the fifth child (third son) of Purnashashi Devi and Kula Chandra Dey. Part of his early childhood was spent in various rural locations in Midnapur in Bengal and Singbhum, then in Bihar, where his father was posted as a police officer. It is possible that as a young boy Manishi was much influenced by fine artistic sense that prevailed in the family through Purnashashi Devi. She was not only an expert in Kantha embroidery, but a fine slate-carver as well.1 It is extremely interesting to note that all the siblings had fine sense of drawing and draftsman like precision in their artistic efforts later in life. Manishi’s eldest brother Mukul Dey was already regularly exhibiting at Indian Society of Oriental Art since its sixth annual exhibition in February, 1913.2 His sisters, Annapurna and Rani (later well known as Rani Chanda), were accomplished in various arts and crafts. Manishi’s youngest brother Suhas Dey was a very sensitive artist in his own right. Over and above, there was a direct influence of the illustrious Tagores of Jorasanko on this family, which was responsible for a general cultural uplift.

In late-1917, after his father’s untimely death, Manishi was sent to Santiniketan school of Rabindranath Tagore3 where he may have studied for a period of about four years. In 1918-19, as Nandalal Bose joined Kala-Bhavan, Manishi got an opportunity to study under him, though, for a very short period of time. About his early schooling at Santiniketan a reviewer in the Illustrated Weekly of India writes: “His early days at school in Santiniketan were too fretful to be preparatory. Conventions cramped him, made him mutinous. It might have ended in a waste of potential power, and bitter frustration. But luck favoured the youngster. He came into contact with Abanindranath Tagore and became a pupil of the great master.”4

Years of apprenticeship under Abanindranath Tagore were most fruitful for Dey. It was really under Abanindranath that he blossomed into a creative artist. For “in India’s art history Abanindranath’s place is unique. Not only has he been unsurpassed as painter, not only was he the moving spirit of the renaissance in Indian art, he was a great teacher as well, a very human teacher who took infinite pains with his pupils. He did not impose on them his own ideas and idiom. He let each develop on an individual line. His influence was limited to bringing out the best in them all.”5

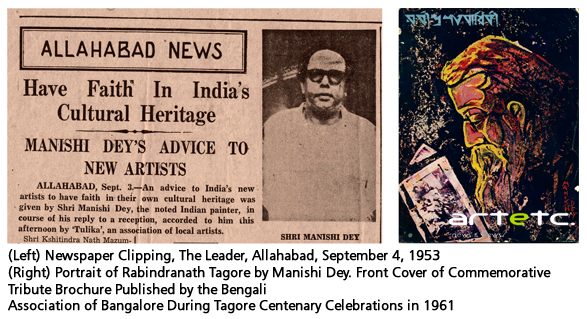

Since 1928 Manishi Dey had been exhibiting his works regularly throughout India, and in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). In fact, he showed his works at many such Indian small towns where many of today’s artists would never dream of taking their art to. He started exhibiting from Nagpur (1928) and went on to show at Madras (1929), Bangalore (1930), Ceylon (1930), Bombay (1932), Shrinagar (1932), Arah (1934), Benares (1934), Nainital (1936), Bombay (1937), Pune (1939), Kolhapur (1940), Baroda (1942), Gwalior (1944), Delhi (1947), Bombay (1950), Allahabad (1953), Bangalore (1957), Ootacamund (1959), Madras (1960) and Trivandrum (1961).6

The year 1949 was a landmark in Dey’s career. He painted a series of twenty-two moving images of non-Muslim refugees who migrated into independent India from newly created Pakistan. Their agony and pain, death destruction and disease, their hunger and fear were captured in nearly monochrome bold brush strokes and low-key chiaroscuro. The paintings in this series were eloquent with mute suffering of the victims, and resulting tragedy due of our leaders’ ambition leading to a political farce of most hideous nature. It is very much possible that Manishi’s close interaction with the members of the Progressive Artists Group of Bombay during late 1940s had resulted in this striking break from the visual idioms popularized by neo-Bengal school. The entire series was collected by Sindhi merchant Pratap Dayaldas.7

Around 1949—50 Dey had close interactions with Delhi artists. One of his intimate friends, Sailoz Mukherjea was there, as well as Biswanath Mukherji, D. Badri and a young art student Shantanu Ukil. Sailoz was teaching then at Delhi Polytechnic during daytime and at Sarada Ukil School of Art in the evenings. Both were extremely fond of their drinks and had a number of spirited adventures culminating in proletariat dinners at a cheap eating-house run by refugee Punjabis just at the periphery of Connaught Circus—Delhi was a different place sixty years ago; else Manishi Dey and his friend Sailoz Mukherjea would have been taken into custody a number of times!8 About this time Dr. M. S. Randhawa acquired a fine collection of Dey’s works for the permanent gallery of AIFACS in New Delhi.9

As with his life, Manishi experimented endlessly with medium and various painting surfaces. Some precious information could be gleaned from Shantanu Ukil’s reminiscence:

“[Manishi Dey] had his own vision to look at life and depict life. He could create a strange atmosphere in his paintings following Indian-style wash technique, using advantage of surface texture and spatula. I saw his painting for the first time in the annual exhibitions of AIFACS. It was titled The Heads. I still remember that picture. Three or four heads of Santals, just like bronze sculpture pieces, he scraped with a blade—much soothing to eye. And I remember [his] four feet by eight feet Ras-Leela, painted on Muga silk, leaving the texture of raw Muga silk blank. This painting was collected by Seth Jugal Kishore Birla. During those days he paid two thousand rupees for the work… [Manishi Dey] presented me one of his small pictures done on a plank of sandalwood and finished with stipples.”10

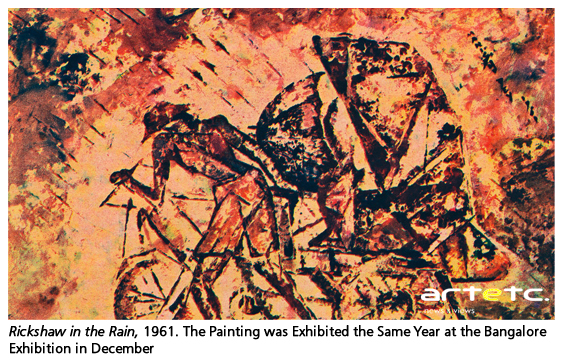

During early 1960s Manishi Dey held at least two major exhibitions at his Brigade Road studio in Bangalore.11 Detailed catalogues were made, and the artist received very favourable notice again in the Illustrated weekly of India. Almost at the sudden end of his career cut short by his untimely death, Manishi Dey received glowing tribute from the pen of Bangalore writer / scholar V. Sitaramiah:

“Manishi Dey has been in Bangalore for seven years now and has exhibited his pictures three times there: once, long ago, in 1930; the second time, in 1957. And recently, in his studio on Brigade Road, he put on show a selection representative of his most recent work. He has now changed his technique radically. One found in these exhibits a freshness and vitality which left his earlier studies far behind. To produce the new effects with line, form, plane and paint, he has changed the softer wash styles and brush techniques and today gives us bolder, ridged and relief modes of presentation. Considering the time and attention bestowed on them, the effect is most striking; and there is a greater imaginative fertility. One would say that Manishi Dey was entering his red-and-orange period…Curves are less in evidence, while angles and other geometrical forms are more freely used. This represents a modernism without abstruseness and tears; free from willfulness and fads; and certainly with no like-me-and-understand-me-if-you-care-or-dare attitude. There is no sophistication or deliberate primitiveness; no straining after “purity”.”12

In touching eloquence Sitaramiah concludes his review, which in retrospect sounds almost like an epitaph:

“Through three decades of painting, searching tirelessly for modes and values, and presenting his vision of life in terms of pictorial, Manishi Dey has gained assurance and power and feels that he is near the end of his search…Supported by the blessings of his gurus and his own indomitable genius, it should be possible for him to withstand every shock of fortune and win.”13

On January 31, 1966 Manishi Dey passed away in Calcutta at the height of his promising artistic career.

References

1. Mukul Dey, Amar Katha, Visva-Bharati 1995, p. 1

2. Ref. original catalogue of 1913 ISOA exhibition in Mukul Dey Archives collection.

3. See Mukul Chandra Dey, Japan Theke Jorasanko: Chithi O Dinalipi (1916—1917), ed. Satyasri ukil, New Age Publishers, Kolkata 2005.

4. See ‘Refugee Nightmare’, review of Manishi Dey’s Refugee Series in the Illustrated Weekly of India, early 1950s. As the copy in Mukul Dey Archives collection is badly damaged, it was not possible to mention the exact date of publication.

5. ibid.

6. Ref. original catalogue of Manishi Dey’s exhibition at his Bangalore studio, December 1961. The catalogue is extremely important as it lists in detail the artist’s past exhibitions and paintings in collection. Mukul Dey Archives collection.

7. In this connection it is important to note Gandhi’s conversation to Pratap Dayaldas on or before May 7, 1947 published in ‘Harijan’ of May 25, 1937. About impact of Hindu-Muslim riots in pre / post-partition India on PAG’s works see Ratan Parimoo and Nalini Bhagwat, Progressive Artists Group of Bombay: An Overview, artetc. news & views, January 2012, p. 6.

8. See reminiscences of Shantanu Ukil in Bengali literary journal ‘Naborupe Subarnorekha’, Magh, 1400 Bangabda, pp. 17—20.

9. B. P. Pal, Association of Dr. M. S, Randhawa with All India Fine Arts and Crafts Society, Roopa-Lekha, vol. 1 & 2, p. 11.

10. Reminiscences of Shantanu Ukil as mentioned above.

11. The studio was located at 133—C, Brigade Road, Bangalore.

12. V. Sitaramiah. New Work by Manishi Dey, The Illustrated Weekly of India, July 8, 1962.

13. ibid.