- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- The Enigma That was Souza

- Progressive Art Group Show: The Moderns

- The Souza Magic

- M.F. Husain: Other Identities

- From All, One; And From One, All

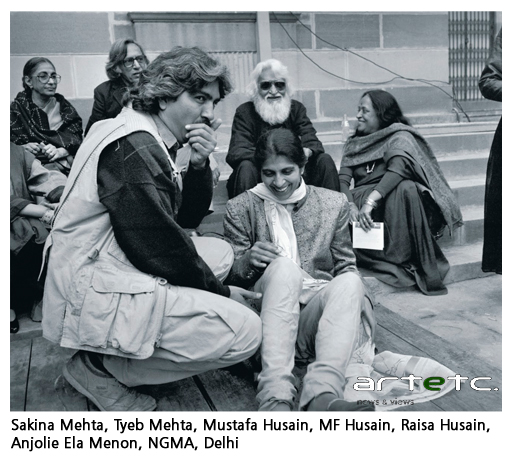

- Tyeb Mehta

- Akbar Padamsee: The Shastra of Art

- Sensuous Preoccupations of V.S. Gaitonde

- Manishi Dey: The Elusive Bohemian

- Krishen Khanna: The Fauvist Progressive

- Ram Kumar: Artistic Intensity of an Ascetic

- The Unspoken Histories and Fragment: Bal Chhabda

- P. A. G. and the Role of the Critics

- Group 1890: An Antidote for the Progressives?

- The Subversive Modernist: K.K.Hebbar

- Challenging Conventional Perceptions of African Art

- 40 Striking Indian Sculptures at Peabody Essex Museum

- Tibetan Narrative Paintings at Rubin Museum

- Two New Galleries for the Art of Asia opens at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

- Raphael, Botticelli and Titian at the National Gallery of Australia

- The Economics of Patronization

- And Then There Was Zhang and Qi

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Random Strokes

- Yinka Shonibare: Lavishly Clothing the Somber History

- A Majestic “Africa”: El Anatsui's Wall Hangings

- The Idea of Art, Participation and Change in Pistoletto’s Work

- On Wings of Sculpted Fantasies

- The Odysseus Journey into Time in the Form of Art

- On Confirming the Aesthetic of Spectacle: Vidya Kamat at the Guild Mumbai

- Dhiraj Choudhury: Artist in Platinum Mode

- Emerging from the Womb of Consciousness

- Gary Hume - The Indifferent Owl at the White Cube, London

- Daum Nancy: A Brief History

- Experimenting with New Spatial Concepts – The Serpentine Gallery Pavilion Project

- A Rare Joie De Vivre!

- Art Events Kolkata-December 2011– January 2012

- Art Bengaluru

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Delhi Dias

- Musings from Chennai

- Preview, February, 2012- March, 2012

- In the News-January 2012

ART news & views

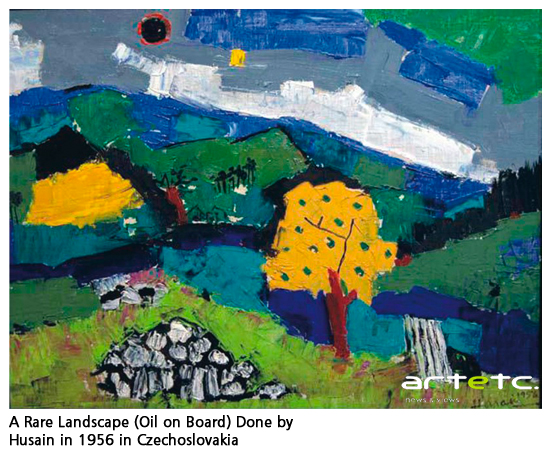

M.F. Husain: Other Identities

Issue No: 25 Month: 2 Year: 2012

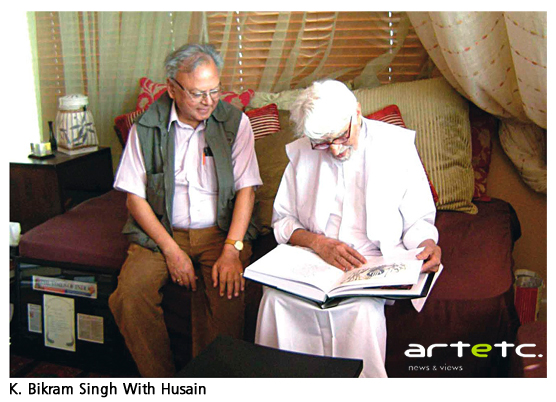

by K. Bikram Singh

Gunter Grass in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech had declared in anguish, “I come from the land of book burning.” Perhaps, his reference was to the experience of Nazi Germany though the metastasis of this cancer continued to erupt even in post–Nazi Germany. Maqbool Fida Husain on his deathbed in a London hospital could have also lamented, “I come from the land where paintings are burnt” but he did not. Technicalities of citizenship apart, Husain remained an Indian till his last breath and never complained about the fate that his country had meted out to him.

Gunter Grass in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech had declared in anguish, “I come from the land of book burning.” Perhaps, his reference was to the experience of Nazi Germany though the metastasis of this cancer continued to erupt even in post–Nazi Germany. Maqbool Fida Husain on his deathbed in a London hospital could have also lamented, “I come from the land where paintings are burnt” but he did not. Technicalities of citizenship apart, Husain remained an Indian till his last breath and never complained about the fate that his country had meted out to him.

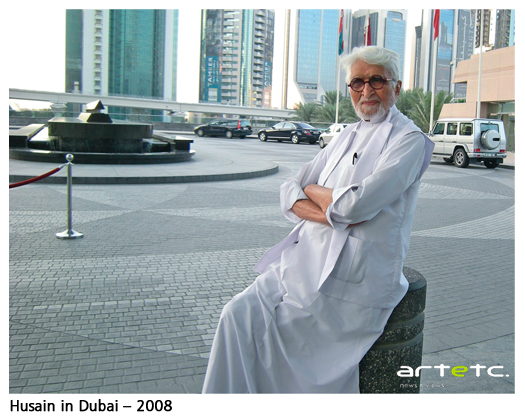

I last spoke to Husain in March 2011 over the phone. He was then in Dubai preparing to go to London. I had teased him, “Now that you are no longer an Indian citizen I hope you can come to India as a Qatar tourist!” He laughed and then became a little sad and emotional, “Marne se pehle ek baar apne watan ki mitti chhoone zaroor aaunga... Before I die, I shall definitely come once to touch the soil of my beloved country.”

This was not to be. When Husain died on 9th June 2011, neither in the country of his birth nor in his adopted country, nor in Dubai where he had set up a second home but in London, the era of liberalism in the visual arts of India came to an end. I say visual arts and not literature because it is far more difficult to destroy all copies of a book than to burn a single painting. That these art vandals have been encouraged by the fate of Husain, is clear from the recent attack on Balbir Krishan’s paintings displayed in a gallery of Lalit Kala Akademi in Delhi. The emboldened attitude of the art vandals remains an unpleasant phenomenon without discounting the possibility that for some artists inviting attacks has become a sort of shortcut to instant publicity. But let me not get political just yet as my brief is to write on my personal relationship with Husain. So let me begin from the beginning.

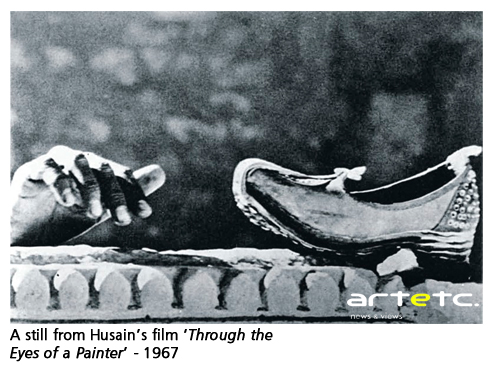

From 1963 to early 1971 I was posted in Mumbai, then called Bombay, with the Western Railways. I was living in Budhwar Park on Wodehouse Road, the other end of which directly led to Jehangir Art Gallery. By the late 1960s my interest in serious cinema and art had considerably grown and Jehangir Art Gallery had become one of my regular haunts. M.F. Husain with his tall frame, loping walk and flowing beard was already a very visual presence on the art scene of Bombay. His Zameen had won the National Award of Lalit Kala Akademi in 1955. The President had honoured him with Padma Shri in 1966. He had directed his first documentary, Through the Eyes of a Painter for the Films Division in 1967 that had won the Golden Bear Award at the Berlin Film Festival. The horse had already become a recurring motif in his paintings that were being lapped up by the elite. In fact, he was fond of saying, “I make films and sell horses.”

From 1963 to early 1971 I was posted in Mumbai, then called Bombay, with the Western Railways. I was living in Budhwar Park on Wodehouse Road, the other end of which directly led to Jehangir Art Gallery. By the late 1960s my interest in serious cinema and art had considerably grown and Jehangir Art Gallery had become one of my regular haunts. M.F. Husain with his tall frame, loping walk and flowing beard was already a very visual presence on the art scene of Bombay. His Zameen had won the National Award of Lalit Kala Akademi in 1955. The President had honoured him with Padma Shri in 1966. He had directed his first documentary, Through the Eyes of a Painter for the Films Division in 1967 that had won the Golden Bear Award at the Berlin Film Festival. The horse had already become a recurring motif in his paintings that were being lapped up by the elite. In fact, he was fond of saying, “I make films and sell horses.”

I think I first met Husain in 1969. Gallery Chemould of Kekoo Gandhy had organized the first retrospective of Husain at Jehangir Art Gallery. The retrospective was simply called 21 Years of Painting. I do not recall the paintings that were shown in this retrospective but I do remember sharing a table with Husain in the Samovar Café located in the Jehangir Art Gallery. Samovar was popular for serving interesting snack meals that tasted even better because this café was patronized by some very pretty girls. If my memory serves me right, one of these was Shobha Rajayadhyaksh who later became a celebrity columnist as Shobhaa De.

We mostly talked about his film Through the Eyes of a Painter that after the success at Berlin, had won the National Film Award in 1968. And yes, he did talk about Indira Gandhi whom he had come to know while Jawaharlal Nehru was still the Prime-Minister. His open admiration for Indira Gandhi has stayed with me perhaps because of the Emergency that she declared in 1975 and which Husain had celebrated in three paintings. These are no longer in public domain. Several decades later in late 2005 during the course of researching a book on Husain, when I asked him about his Emergency paintings, he was evasive. But he had no hesitation in saying that had Indira Gandhi been there she would have put a stop to the assaults that he was facing from the Hindutva forces and their accomplices. I could not have agreed with him more. With all her faults Indira Gandhi was a genuinely secular person and did not stand any nonsense on this issue.

We mostly talked about his film Through the Eyes of a Painter that after the success at Berlin, had won the National Film Award in 1968. And yes, he did talk about Indira Gandhi whom he had come to know while Jawaharlal Nehru was still the Prime-Minister. His open admiration for Indira Gandhi has stayed with me perhaps because of the Emergency that she declared in 1975 and which Husain had celebrated in three paintings. These are no longer in public domain. Several decades later in late 2005 during the course of researching a book on Husain, when I asked him about his Emergency paintings, he was evasive. But he had no hesitation in saying that had Indira Gandhi been there she would have put a stop to the assaults that he was facing from the Hindutva forces and their accomplices. I could not have agreed with him more. With all her faults Indira Gandhi was a genuinely secular person and did not stand any nonsense on this issue.

In March 1971 I moved over to Delhi. Years passed and like any other career civil servant I kept on moving from one job to another. Finally, in April 1983 I took voluntary retirement from government service to become a full time filmmaker and a part time writer on art. I was then working as Director (Film Policy) in the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting and my interest in Cinema had by then grown into an obsession. At that time, Triveni Kala Sangam and Dhoomimal Art Gallery were the main centres of art in Delhi which I used to regularly visit.

In the meantime Husain had become a brand in the world of art, a darling of the media and a favoured artist of the political establishment. Except for a brief interregnum of Janta rule, Husain’s favourite politician Indira Gandhi was still ruling over the country. Husain was in the stratosphere. I did run into him once in a while at the Triveni Kala Sangam and the India International Centre but I was acutely aware that Husain had become inaccessible for the likes of me.

During the 1980s, the International Film Festival of India (IFFI) used to be held in Delhi. The Festival had an important section for Indian films called the Indian Panorama. The feature films and documentaries selected for this section got an opportunity of not only being shown at the IFFI but to also participated in several film festivals all over the world. Besides, the Panorama Feature Films received a preferred screening on Doordarshan and an enhanced telecast fee. There was, therefore, an intense competition among the serious filmmakers to get their films into the Panorama.

In 1985, Husain was appointed as the Chairman of the Selection Panel for Feature Films for the Indian Panorama to be shown in January 1986 IFFI. I was one of the panel members. The panel was required to select 21 feature films out of more than 80 films that were offered for the selection. By then Indira Gandhi was gone and her son Rajiv Gandhi had become the Prime Minister. Pupul Jayakar who was the Cultural Advisor to Indira Gandhi had now become the Cultural Advisor to Rajiv Gandhi. She had a finger in everything that even remotely concerned culture.

Husain had no qualifications to be the Chairman of the Panorama Selection Panel. He had made only one documentary and no feature films. But in fairness to Husain I must add that the government has never considered cinema as a serious art form. Therefore unlike the Juries for selection of paintings or books anybody with common sense is considered qualified to judge films. And after all Husain was not only a star celebrity but also close to the powers that be. Husain came to the panel meeting on the first day and then disappeared for the next two weeks. The members requested Chidananda Dasgupta, who was also in the panel, to informally work as the Chairman. Over the next two weeks or so, the panel reached unanimity on twenty films to be selected but there were sharp differences on the last film. I was arguing for the first film of a Bengali director and after discussion several other members were inclined to support me.

One of the entries for the selection was Mani Kaul’s Mati Manas, a feature length documentary on traditional potters. There was no provision then in the rules to include feature length documentaries within the category of feature films in the Indian Panorama. It was, therefore, unanimously rejected even though it was visually a stunning film.

On the last day of the panel meeting Husain suddenly reappeared and suggested that we should include Mani Kaul’s film. I protested that it was a documentary and its inclusion would deprive a young filmmaker of an important chance of showcasing his film at International Film Festivals. At this point Chidananda Dasgupta intervened and pleaded that the panel should include Mani Kaul’s Mati Manas in deference to the wishes of the Chairman – even though the Chairman had not seen most of the other films. Thus I was overruled. Justice and fair play were sacrificed at the altar of deference!

I knew that both Husain and Mani Kaul were close to Pupul Jayakar, then czarina of Indian culture. Had she something to do with this sudden interest of Husain in Mani Kaul’s film? I cannot say but I was deeply upset by the thoughtlessness of Husain. Next evening, Husain hosted a dinner for the panel members at the Jangpura flat of his son Shamshad where he used to stay when in Delhi. Good food, good liquor, warmth and charm, Husain was the perfect host. I was still simmering. At one point I took the liberty of bluntly telling Husain how unfair he had been in imposing Mani Kaul’s film and even added that it was this kind of who-knows-whom that made a mockery of our search for excellence in life and art. Always a gentleman Husain took my outburst without showing any offence.

Husain had come down a few notches in my eyes. But I also realized that like all of us he too had several identities. In fact, being highly gifted Husain had more than his share of identities, split as these were between his commitment to himself, his deep-rooted sense of personal freedom, his celebration of the syncretic culture of India and his humanism. However, after this encounter I did not try to contact or meet Husain for several years though I continued to follow his work.

In 1996, I decided to make a documentary on his son Shamshad for Doordarshan as a part of a series called A Painter’s Portrait. I thought a comment from M.F. Husain would be relevant and interesting. He was then living in Bombay. He readily agreed to my request and came to Delhi for the interview. Quite contrary to his reputation he appeared at Shamshad’s flat on the appointed time. Shamshad had by then moved to a new address near Gole Market. Perhaps, some understanding of a filmmaker’s compulsions had rubbed on Husain in addition to his love for his son. He knew that a filmmaker has to always carry a team and he can ill afford a wasted day.

One of the questions that I had asked him on camera was, “How was Shamshad as a young boy?” Shamshad had already told me that as a school boy he was more interested in street fights than boring pursuits like painting. Husain replied to my question in Urdu, “They to bade shaitan lekin kyunki hamari darhi lambi thi isliye hamara zara lihaaz karte the… He was very naughty but since I had a long beard he was rather respectful to me.”

This experience of talking to Husain about his children made me aware for the first time how deeply he loved his family. But unlike most other people for Husain this love for the family was a starting point of his love for the ordinary human being and for all things human. Besides, his love was undemanding, made even lighter by his sense of humour. It is this light and fun-filled love that permeates a large body of Husain’s work.

This is one of the pathways in Husain’s deeply forested mind that led him to Ramayana. After all what is myth if not a mediation between the ordinary, the fantastic and the eternal, full of love, humour and terror. It is another matter that sometimes some things that we create out of love for our home or homeland can be twisted to accuse us of spoiling our own nest. Husain’s Ramayana paintings were made out of love, respect and a sense of fun that we have all experienced while watching the Ramlila in our villages or small towns. That these became the spark for igniting the conflagration that pushed Husain into exile and that reduced the so called secular government to a mere spectator had nothing to do with Husain’s paintings. It had to do with the deliberate communalization of political discourse in our country that had started immediately after the fall of the Janta government in 1977 and the formation of a political party with an open Hindutva ideology.

I was to meet Husain more intimately and get to know him and his work more closely, a few years later between 2005 and 2008 when I was writing a book on his work. By then, attacks on him had already gained momentum. That, however, is another story. For the present I can only say that modernity has taken away from us the option of worshipping perfect gods. We can only admire imperfect heroes. For me Maqbool Fida Husain was one of them.