- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- The Enigma That was Souza

- Progressive Art Group Show: The Moderns

- The Souza Magic

- M.F. Husain: Other Identities

- From All, One; And From One, All

- Tyeb Mehta

- Akbar Padamsee: The Shastra of Art

- Sensuous Preoccupations of V.S. Gaitonde

- Manishi Dey: The Elusive Bohemian

- Krishen Khanna: The Fauvist Progressive

- Ram Kumar: Artistic Intensity of an Ascetic

- The Unspoken Histories and Fragment: Bal Chhabda

- P. A. G. and the Role of the Critics

- Group 1890: An Antidote for the Progressives?

- The Subversive Modernist: K.K.Hebbar

- Challenging Conventional Perceptions of African Art

- 40 Striking Indian Sculptures at Peabody Essex Museum

- Tibetan Narrative Paintings at Rubin Museum

- Two New Galleries for the Art of Asia opens at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

- Raphael, Botticelli and Titian at the National Gallery of Australia

- The Economics of Patronization

- And Then There Was Zhang and Qi

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Random Strokes

- Yinka Shonibare: Lavishly Clothing the Somber History

- A Majestic “Africa”: El Anatsui's Wall Hangings

- The Idea of Art, Participation and Change in Pistoletto’s Work

- On Wings of Sculpted Fantasies

- The Odysseus Journey into Time in the Form of Art

- On Confirming the Aesthetic of Spectacle: Vidya Kamat at the Guild Mumbai

- Dhiraj Choudhury: Artist in Platinum Mode

- Emerging from the Womb of Consciousness

- Gary Hume - The Indifferent Owl at the White Cube, London

- Daum Nancy: A Brief History

- Experimenting with New Spatial Concepts – The Serpentine Gallery Pavilion Project

- A Rare Joie De Vivre!

- Art Events Kolkata-December 2011– January 2012

- Art Bengaluru

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Delhi Dias

- Musings from Chennai

- Preview, February, 2012- March, 2012

- In the News-January 2012

ART news & views

Gary Hume - The Indifferent Owl at the White Cube, London

Issue No: 25 Month: 2 Year: 2012

by Preeti Kathuria

Almost four years back I saw Gary Hume's astonishing Door Paintings at the Modern Art Oxford and the playful abstraction of those large-scale, glossy, painted institutional-doors is still fresh in my mind. Doors tend to create distance and separation among spaces but Hume's door-paintings hung on the walls dissolved that distance; they came across as a multitude of inviting facades, where each set of doors had a distinctive pictorial logic and configuration. A strategic coherence of the doors as an object not only camouflaged the gallery walls but also accentuated the visitor's experience of scale and space. An exhibition of Hume's new paintings and sculptures recently opened at the White Cube, London and the show seemed like a seamless extension to Hume's artistic practise.

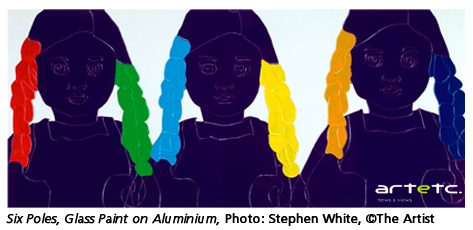

By making room for multiple ways of interpreting each work, the show opened up various perspectives that the exhibition invited the visitor to explore and consume. The exhibition's title makes a reference to the Owl a mystical yet wise and insightful creature; who agreeably shares these characteristics with the attributes of this exhibition. The Indifferent Owl, was a tondo painted in subtle hues of browns and blues amidst a group of paintings of flowers and plants that suggested Hume's fascination for the spectacle offered by nature. His Paradise Paintings depicting stylized flora and fauna, seem to de-contextualize the visitor from the white-cube confines of the gallery. The vibrant red rose in the Pink Rent, the pearl-white sparrow against a yellow background in The Mother and the young school girls in 'Six Poles' all throb with a notoriously obscured youthful impulse of subjectivity. A starkly gazing, minimalistic portrait of the late pop-icon Michael Jackson shows tension and encounter addressing the human condition and temporality. One is inclined to draw a radical continuity in the simplified depictions of a complex grammar. As Hegel appropriately points out: 'Painting… opens the way for the first time to the principle of finite and inherently infinite subjectivity, the principle of our own life and existence, and in paintings we see what is effective and active in ourselves'. Hume also exhibited, for the first time, a group of new sculptures carved from white limestone, but somehow his paintings expend greater energy, reach out faster, diminish distances and build more dialogues with the visitors. 'Neither literal nor illusionistic,' writes Jennifer Higgie, co-editor of the Frieze Magazine, in her catalogue essay, Hume's paintings 'draw you into the depths of something you might have initially assumed was all surface.'

By making room for multiple ways of interpreting each work, the show opened up various perspectives that the exhibition invited the visitor to explore and consume. The exhibition's title makes a reference to the Owl a mystical yet wise and insightful creature; who agreeably shares these characteristics with the attributes of this exhibition. The Indifferent Owl, was a tondo painted in subtle hues of browns and blues amidst a group of paintings of flowers and plants that suggested Hume's fascination for the spectacle offered by nature. His Paradise Paintings depicting stylized flora and fauna, seem to de-contextualize the visitor from the white-cube confines of the gallery. The vibrant red rose in the Pink Rent, the pearl-white sparrow against a yellow background in The Mother and the young school girls in 'Six Poles' all throb with a notoriously obscured youthful impulse of subjectivity. A starkly gazing, minimalistic portrait of the late pop-icon Michael Jackson shows tension and encounter addressing the human condition and temporality. One is inclined to draw a radical continuity in the simplified depictions of a complex grammar. As Hegel appropriately points out: 'Painting… opens the way for the first time to the principle of finite and inherently infinite subjectivity, the principle of our own life and existence, and in paintings we see what is effective and active in ourselves'. Hume also exhibited, for the first time, a group of new sculptures carved from white limestone, but somehow his paintings expend greater energy, reach out faster, diminish distances and build more dialogues with the visitors. 'Neither literal nor illusionistic,' writes Jennifer Higgie, co-editor of the Frieze Magazine, in her catalogue essay, Hume's paintings 'draw you into the depths of something you might have initially assumed was all surface.'

Illuminating glosses of paint on aluminium are Hume's primary tools to unfold his painterly narratives. Hume's admirable intention to paint intimate manifestations of nature or even objects, take on a more formidable challenge due to the materials employed by him. The bold, print-like quality of the works, make them appear uncomplicated and utterly whimsical. The works, collectively communicate the eloquent indifference in our lives where one exists in solitary, self-contained contours and ridges yet projects a decorative, gleamy exterior. It is worthwhile to see how these polarities get substantiated and materialised in the flatness of Hume's paintings. The process of creation and reception of art hardly ever gets linearly streamlined but this show is curiously exceptional for its highly communicable and engaging works.