- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- The Enigma That was Souza

- Progressive Art Group Show: The Moderns

- The Souza Magic

- M.F. Husain: Other Identities

- From All, One; And From One, All

- Tyeb Mehta

- Akbar Padamsee: The Shastra of Art

- Sensuous Preoccupations of V.S. Gaitonde

- Manishi Dey: The Elusive Bohemian

- Krishen Khanna: The Fauvist Progressive

- Ram Kumar: Artistic Intensity of an Ascetic

- The Unspoken Histories and Fragment: Bal Chhabda

- P. A. G. and the Role of the Critics

- Group 1890: An Antidote for the Progressives?

- The Subversive Modernist: K.K.Hebbar

- Challenging Conventional Perceptions of African Art

- 40 Striking Indian Sculptures at Peabody Essex Museum

- Tibetan Narrative Paintings at Rubin Museum

- Two New Galleries for the Art of Asia opens at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

- Raphael, Botticelli and Titian at the National Gallery of Australia

- The Economics of Patronization

- And Then There Was Zhang and Qi

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Random Strokes

- Yinka Shonibare: Lavishly Clothing the Somber History

- A Majestic “Africa”: El Anatsui's Wall Hangings

- The Idea of Art, Participation and Change in Pistoletto’s Work

- On Wings of Sculpted Fantasies

- The Odysseus Journey into Time in the Form of Art

- On Confirming the Aesthetic of Spectacle: Vidya Kamat at the Guild Mumbai

- Dhiraj Choudhury: Artist in Platinum Mode

- Emerging from the Womb of Consciousness

- Gary Hume - The Indifferent Owl at the White Cube, London

- Daum Nancy: A Brief History

- Experimenting with New Spatial Concepts – The Serpentine Gallery Pavilion Project

- A Rare Joie De Vivre!

- Art Events Kolkata-December 2011– January 2012

- Art Bengaluru

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Delhi Dias

- Musings from Chennai

- Preview, February, 2012- March, 2012

- In the News-January 2012

ART news & views

P. A. G. and the Role of the Critics

Issue No: 25 Month: 2 Year: 2012

by Vrushali Dhage

Defining the role of a critic, as a viewer, observer or as an individual, responsible for passing judgements based on works of art, is an issue which certainly moves beyond objectivity and becomes a terrain with no specific demarcations as limiting fences. Further the critical text produced, too, becomes a work open for multiple interpretations; locating it in the critic’s reference to – the artistic and aesthetic concerns, its sites of origin, its objectives, spaces of publication, its audience and also moving beyond into a much broader network of social and political concerns, both historically and within the contemporary times. The text then could range from being a rigid one-time judgement to a constant dialectic thought, open for interpretation and revision; as a simple response to a work of art, to a continuous tracing and analysis of an artist’s creative trajectory, both at a professional and personal level; a vox populi based on general notions of acceptance, to a personal dispassionate critical one; a simple descriptive literature, as opposed to a judgement seeking to mobilise.

A cursory view across the mass of critical texts produced in reference to the PAG (Progressive Artists’ Group) as a singular entity and also the independent individual artists evidently highlights radically polar opinions and statements. These range from declaring their works as degraded art, to art that has a non-sedentary progressive offering, moving from beautiful, pretty pictures to those adopting a modernist stance by portraying the present in a bold manner. Within the multiplicity of such voices, one needs to move beyond counting the number of supporters and opponents, and needs to take cognisance of their critical statements, as these statements not only enlist various opinions of various artists and critics but also portray a first hand picture of the then existing art scenario, which was in a state of constant flux.

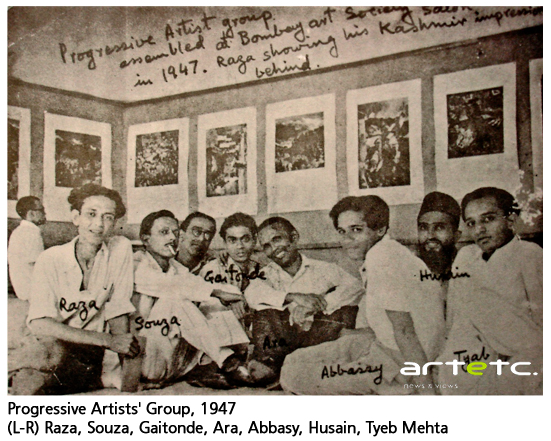

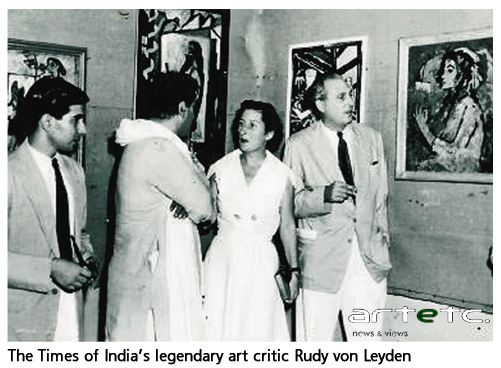

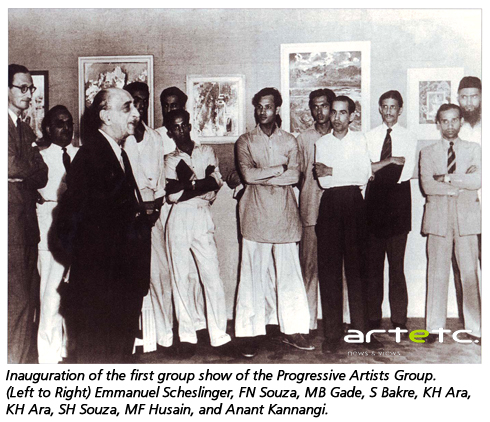

While speaking about the contribution of critics to the PAG, three individuals of surmounting importance are, Rudolf von Leyden, Walter Langhammer and Emmanuel Schlesinger. The three were war émigrés from Europe, who immigrated to India after the rise of Nazism in Europe. They played a dominant role in the field of Indian art, primarily in Mumbai (then Bombay). Langhammer was an art teacher from Austria, on the insistence of his Indian student, Shirin Vimadalal, in 1938 Langhammer came to India with his wife, Kathe. Through Vimadalal he joined the Times of India as the director of its art department. Langhammer along with Kathe ran a salon at his Nepean Sea Road residence, inviting artists to have discussions and also work at their convenience. Being a practitioner Langhammer painted and exhibited at the Bombay Art Society. Emmanuel Schlesinger came to India in early 40’s. A pharmacist by profession, he established Indo-Pharma Company in India. An avid collector of art, Schlesinger had left behind a large number of paintings when leaving Germany. In India Schlesinger bought works of young, emerging artists. Rudolf von Leyden, Rudi, as was usually addressed, came to India in 1933, when all communist deputies were detained in Germany, following the burning of the Reichstag. A geologist by training, in India he worked as a Publicity Manager for Volkart Brothers. He was also an art critic, a cartoonist, a photographer and a painter (often worked in water-colours). Later he was to become the official art critic for the Times of India and also contributed cartoons to the Illustrated Weekly of India, under the pseudonym, Denley.

While speaking about the contribution of critics to the PAG, three individuals of surmounting importance are, Rudolf von Leyden, Walter Langhammer and Emmanuel Schlesinger. The three were war émigrés from Europe, who immigrated to India after the rise of Nazism in Europe. They played a dominant role in the field of Indian art, primarily in Mumbai (then Bombay). Langhammer was an art teacher from Austria, on the insistence of his Indian student, Shirin Vimadalal, in 1938 Langhammer came to India with his wife, Kathe. Through Vimadalal he joined the Times of India as the director of its art department. Langhammer along with Kathe ran a salon at his Nepean Sea Road residence, inviting artists to have discussions and also work at their convenience. Being a practitioner Langhammer painted and exhibited at the Bombay Art Society. Emmanuel Schlesinger came to India in early 40’s. A pharmacist by profession, he established Indo-Pharma Company in India. An avid collector of art, Schlesinger had left behind a large number of paintings when leaving Germany. In India Schlesinger bought works of young, emerging artists. Rudolf von Leyden, Rudi, as was usually addressed, came to India in 1933, when all communist deputies were detained in Germany, following the burning of the Reichstag. A geologist by training, in India he worked as a Publicity Manager for Volkart Brothers. He was also an art critic, a cartoonist, a photographer and a painter (often worked in water-colours). Later he was to become the official art critic for the Times of India and also contributed cartoons to the Illustrated Weekly of India, under the pseudonym, Denley.

One can categorise the contributions of the three émigrés in a nearly distinct manner. Langhammer, as a practicing artist, who was well versed with the prevailing European styles, introduced the artists of the PAG to the same, styles which were radically different from that of Academic Realism that was taught at the Sir. J. J. School of Arts. Schlesinger, an art collector, primarily provided financial aid by creating working opportunities for the artists and also by collecting works of young promising artists. Schlesinger had a strong understanding of art and a keen deciphering eye. Leyden played a large role not only as a critic to the works of art but also to the conditions under which art was made. Backed with a thorough knowledge of art – both Indian and Western, his insight towards Indian contemporary art and his essays on the same, advocate the urgent need for an energetic force (through new blood) of modernism to alter the then existing course of art in the country. Like Leyden, Langhammer and Schlesinger too had strong views and opinions about the contemporary practices and analysed the works of the artists in their individual ways.

The salon at Langhammer’s was not just a physical space where artists could work but became a space of intellectual ferment. As Raza recalls, Langhammer would place in front of them works of Raphael, El Greco, Monet and Cezanne and even Persian, Rajput and Mughal miniatures, thereby expanding their horizons of exposure to various styles of art, which led to an awareness of form and an emergence of an attitude which was increasingly eclectic and less imitative. Watching Langhammer creating quick, bold impastos, in an expressionist manner of Kokoschka, impressed Raza and Ara immensely. An influence of Langhammer’s rapid and spontaneous handling of broad brush strokes was seen in Raza’s, Bori-Bunder (1947), such that one sees an evident departure from the old realist style. Langhammer a keen observer of the individual styles of the artists, he provided them with multiple visual possibilities which could be employed by them while executing their works. Ara for instance, who lacked rudimentary training and a singular style of working was encouraged by Langhammer and Charles Gerrard, Director of Sir J. J. School of Art, to execute his works in a uninhibited manner – free approach to all subjects, manner and styles. As Gerrard stated, “Ara’s work is the best when it cannot be classified, where it is just ‘Ara’.” Leyden was credited in “spotting” the talent of these two artists.

The salon at Langhammer’s was not just a physical space where artists could work but became a space of intellectual ferment. As Raza recalls, Langhammer would place in front of them works of Raphael, El Greco, Monet and Cezanne and even Persian, Rajput and Mughal miniatures, thereby expanding their horizons of exposure to various styles of art, which led to an awareness of form and an emergence of an attitude which was increasingly eclectic and less imitative. Watching Langhammer creating quick, bold impastos, in an expressionist manner of Kokoschka, impressed Raza and Ara immensely. An influence of Langhammer’s rapid and spontaneous handling of broad brush strokes was seen in Raza’s, Bori-Bunder (1947), such that one sees an evident departure from the old realist style. Langhammer a keen observer of the individual styles of the artists, he provided them with multiple visual possibilities which could be employed by them while executing their works. Ara for instance, who lacked rudimentary training and a singular style of working was encouraged by Langhammer and Charles Gerrard, Director of Sir J. J. School of Art, to execute his works in a uninhibited manner – free approach to all subjects, manner and styles. As Gerrard stated, “Ara’s work is the best when it cannot be classified, where it is just ‘Ara’.” Leyden was credited in “spotting” the talent of these two artists.

Schlesinger unlike Leyden or Langhammer was not a practitioner but a connoisseur of art. A matter of interest is the rapport he shared with artist on a personal basis. Having a good understanding of the financially hard-pressed conditions of the artists, Schlesinger tried to provide monetary help by even commissioning young artists to paint which would then be produced in the calendar of his company. Holck Larsen of Larsen and Tubro and Wayne Hartwell, Cultural officer of United States Information Service, who provided Bakre with a working space, were art collectors too, but it was Schlesinger who went beyond being a buyer of the final completed work, as he was an observer and discussant of their artistic processes too.

The role of Leyden, with respect to the PAG was much more diverse as he was instrumental in cultivating an attitude, an awareness of the need of the time for renewed ideas and working methods, of stressing on the urgency to move beyond the limited nationalistic constraints to broadened spheres, a role of art, an artist, a critic and recipients of criticism in the (then) contemporary society, thereby guiding the nation towards modernism, which aimed at de-shackling the present from the grip of sedated traditionalism towards dynamic internationalism.

Leyden’s mistrust in nationalistic sentiments and his notions of a constructive nation were expressed in his write-up, What Free India Means to Me, Independence Supplement, The Times of India, August 1949, and Artists In The New Republic, Republic Day Supplement, Times of India, 26 January, 1950, in which he defines the role of a contemporary artist, not as an isolated practitioner but an individual aware of his / her times,"the artist distils the spirit of his day..." (See What Free India Means to Me, Independence Supplement, The Times of India, August 1949).

Stressing on the needs of modernism, he encouraged the departure from the redundant colonial modes like naturalism. This tug in the web at a point, produced ripples elsewhere, nearly prophesying the emergence of a highly charged group; Souza while formulating the manifesto of the PAG galvanised similar opinions. The group with their anti-imperialist outlook aimed at bridging the artists and common people, similar to the manifesto of Die-Bruke, German Expressionist Group. Further according to Leyden this “distinct group”, with the struggle to move beyond the Victorian modes and with some of their deserved works rejected from the annual salons (e.g. Independence Day Parade by Ara), had enough reason to rebel. In the first official meeting of the PAG, held on 15th Dec 1947, the critic, Rashid Husain, spoke strongly against the old orthodox critics, further, in a highly caustic manner Souza ridiculed the redundancy of such bodies and declared that the artists had now chosen to work with absolute freedom.

Leyden describes that each of the artist had developed an individual style. Ara’s works had a sense of spontaneity and intuition and brilliant pictorial imaginations, which Leyden compared to Peter Brueghel. Gade’s

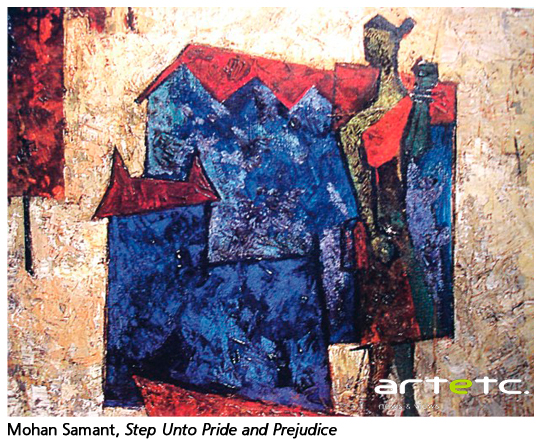

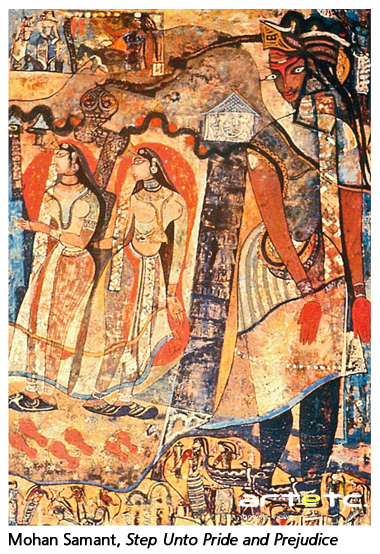

Leyden describes that each of the artist had developed an individual style. Ara’s works had a sense of spontaneity and intuition and brilliant pictorial imaginations, which Leyden compared to Peter Brueghel. Gade’s  landscape and compositions had a strong Cezannia tilt. To Raza’s fluid water-colour landscapes had a near Cubist composition. Bakre unlike commercial artists working on ‘life-like’ sculptures was working to find expression through formal values. Husain emphasised on colour while his forms remained deliberately vague and undefined. In case of Souza, Leyden states that the importance was given more to the subject-matter, and his experimental approach relied heavily on his volatile temperament. The brute force of a nude image, his themes addressing the predicament of man – of religion and sex seemed blasphemous to the viewers, who were accustomed to works done in Victorian modes. As a result their first group show in 1949, was met with heavy criticism, with only few critics corroborating their voice. Leyden in his review mentioned about the “progressive offerings of these artists”, who had moved beyond beautiful-looking paintings to the expressions of the strivings of their generation. Mulk Raj Anand, who opened the show, commended the six Progressives as the “Heralds of a new dawn in the world of India Art.” (Sunday Standard, July 10, 1949). Critic Jagmohan from Sunday Standard too commended their works. Contrary to these laudatory notes Simon Pereira, of Sunday Standard, condemned the show as “a collection of monstrosities by daubers who cannot paint a tree to look like a tree…an insult to intelligence…The fault I believe, is not so much with the artists as with the so called critics whose words these well-meaning young men foolishly take as gospels.” This was aimed directly at Langhammer, Schlesinger and Leyden. This statement gives an idea as to how the three were thought to be the individuals responsible for sowing the thoughts of modernism in the artists. At the same time it is important to note that Leyden even when appreciating their styles, which were an outcome of their eclectic attitude, was always critical of pale imitation of western modes. His criticism towards some of the latter works of the PAG members, like for Raza of slipping down his own set standards, or of Souza lacking self-discipline, makes it clear that Leyden’s support to the PAG was not of blind advocacy, but of continuous unbiased evaluation. His intentions were evidently that of being highly critical such that his text would neither become a pseudo promotive note nor a mere caption line to the work. In his reviews on D. C. Karanjgaokar, V. N. Mali, M. T. Bhopale, P. T. Reddy, Mohan Samant,

landscape and compositions had a strong Cezannia tilt. To Raza’s fluid water-colour landscapes had a near Cubist composition. Bakre unlike commercial artists working on ‘life-like’ sculptures was working to find expression through formal values. Husain emphasised on colour while his forms remained deliberately vague and undefined. In case of Souza, Leyden states that the importance was given more to the subject-matter, and his experimental approach relied heavily on his volatile temperament. The brute force of a nude image, his themes addressing the predicament of man – of religion and sex seemed blasphemous to the viewers, who were accustomed to works done in Victorian modes. As a result their first group show in 1949, was met with heavy criticism, with only few critics corroborating their voice. Leyden in his review mentioned about the “progressive offerings of these artists”, who had moved beyond beautiful-looking paintings to the expressions of the strivings of their generation. Mulk Raj Anand, who opened the show, commended the six Progressives as the “Heralds of a new dawn in the world of India Art.” (Sunday Standard, July 10, 1949). Critic Jagmohan from Sunday Standard too commended their works. Contrary to these laudatory notes Simon Pereira, of Sunday Standard, condemned the show as “a collection of monstrosities by daubers who cannot paint a tree to look like a tree…an insult to intelligence…The fault I believe, is not so much with the artists as with the so called critics whose words these well-meaning young men foolishly take as gospels.” This was aimed directly at Langhammer, Schlesinger and Leyden. This statement gives an idea as to how the three were thought to be the individuals responsible for sowing the thoughts of modernism in the artists. At the same time it is important to note that Leyden even when appreciating their styles, which were an outcome of their eclectic attitude, was always critical of pale imitation of western modes. His criticism towards some of the latter works of the PAG members, like for Raza of slipping down his own set standards, or of Souza lacking self-discipline, makes it clear that Leyden’s support to the PAG was not of blind advocacy, but of continuous unbiased evaluation. His intentions were evidently that of being highly critical such that his text would neither become a pseudo promotive note nor a mere caption line to the work. In his reviews on D. C. Karanjgaokar, V. N. Mali, M. T. Bhopale, P. T. Reddy, Mohan Samant, on Haldankars, also on Shankar Palsikar who was rooted in the Indian aesthetic canons Leyden alters his parameters of judgement. Along with his thoughtful analysis of works of art Leyden also paid due attention to the exhibiting space, be it bad lights or viewing distance Leyden considered all these aspects too. He was pleased when the Bombay Art Society’s annual exhibition took place at the C. J. Hall in 1944 and in Jehangir Art Gallery in 1952 as it gave the display a professional touch.

on Haldankars, also on Shankar Palsikar who was rooted in the Indian aesthetic canons Leyden alters his parameters of judgement. Along with his thoughtful analysis of works of art Leyden also paid due attention to the exhibiting space, be it bad lights or viewing distance Leyden considered all these aspects too. He was pleased when the Bombay Art Society’s annual exhibition took place at the C. J. Hall in 1944 and in Jehangir Art Gallery in 1952 as it gave the display a professional touch.

Leyden’s other serious concern as a critic, along with those dealing with practitioners of art, were that of cultivating the taste of the public and of art collectors. Conceived in this way Leyden’s statements / judgements and criticism then shifts to broader history of consumption and making of art; taking into consideration not just the artists, but also the institutions such as salons, the academies, state cultural policies, art education, private exhibitions, galleries, museums, collectors, publications, thereby placing it in a larger cultural, political and social sphere.

Reference

1. Nalini Bhagwat, Development of Contemporary Art in Western India, Ph. D. Thesis submitted to M. S. University, Baroda, 1983.

2. Yashodhara Dalmia, The Making of Modern Indian Art The Progressives, New Delhi, 2001

3. Ratan Parimoo, Publications, Magazines, Journals, Polemics, Supportive Critical Writings from Charles Fabri to Geeta Kapur, in Fifty Years of Indian Art, Conference Proceedings, Mohile Parikh Centre for the Visual Arts, Mumbai, 1998

4. Newspaper references, Archives, Department of Art History and Aesthetics, Faculty of Fine Arts, M. S. U., Baroda