- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- The Enigma That was Souza

- Progressive Art Group Show: The Moderns

- The Souza Magic

- M.F. Husain: Other Identities

- From All, One; And From One, All

- Tyeb Mehta

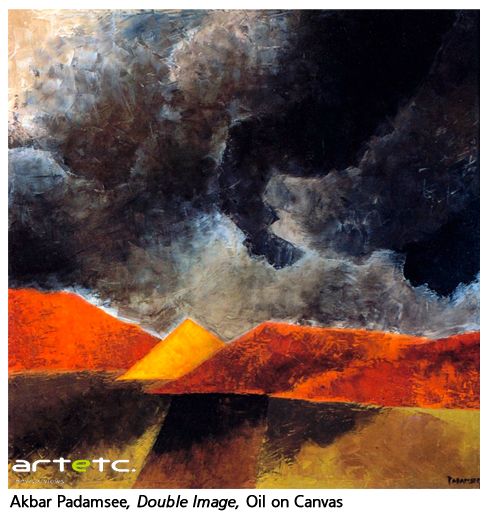

- Akbar Padamsee: The Shastra of Art

- Sensuous Preoccupations of V.S. Gaitonde

- Manishi Dey: The Elusive Bohemian

- Krishen Khanna: The Fauvist Progressive

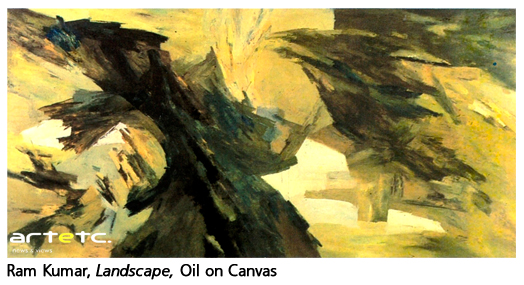

- Ram Kumar: Artistic Intensity of an Ascetic

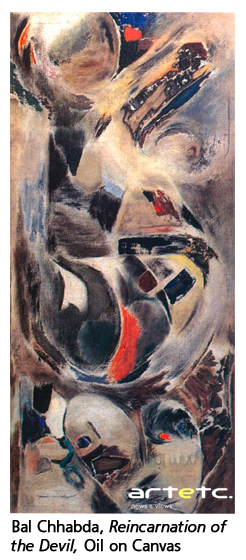

- The Unspoken Histories and Fragment: Bal Chhabda

- P. A. G. and the Role of the Critics

- Group 1890: An Antidote for the Progressives?

- The Subversive Modernist: K.K.Hebbar

- Challenging Conventional Perceptions of African Art

- 40 Striking Indian Sculptures at Peabody Essex Museum

- Tibetan Narrative Paintings at Rubin Museum

- Two New Galleries for the Art of Asia opens at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

- Raphael, Botticelli and Titian at the National Gallery of Australia

- The Economics of Patronization

- And Then There Was Zhang and Qi

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Random Strokes

- Yinka Shonibare: Lavishly Clothing the Somber History

- A Majestic “Africa”: El Anatsui's Wall Hangings

- The Idea of Art, Participation and Change in Pistoletto’s Work

- On Wings of Sculpted Fantasies

- The Odysseus Journey into Time in the Form of Art

- On Confirming the Aesthetic of Spectacle: Vidya Kamat at the Guild Mumbai

- Dhiraj Choudhury: Artist in Platinum Mode

- Emerging from the Womb of Consciousness

- Gary Hume - The Indifferent Owl at the White Cube, London

- Daum Nancy: A Brief History

- Experimenting with New Spatial Concepts – The Serpentine Gallery Pavilion Project

- A Rare Joie De Vivre!

- Art Events Kolkata-December 2011– January 2012

- Art Bengaluru

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Delhi Dias

- Musings from Chennai

- Preview, February, 2012- March, 2012

- In the News-January 2012

ART news & views

Progressive Art Group Show: The Moderns

Issue No: 25 Month: 2 Year: 2012

Revisited

by Nanak Ganguly

Art historically Progressive Art Group has always remained as a bridge between avant garde and the emergent radical Indian Contemporary art of the fifties and sixties. The Group with Mulk Raj Anand as its resident spokesman has always been hailed as progenitor of Modern Art in India. Despite its vast contribution in the making of a language that marks the emergence of an Indian Modern in the sixties always remained a source of inspiration for later generation of artists. This revisit has been an overview of the repertoire especially their devoid of any meta-commentary till date on the basis of his public exhibitions and catalogues available and searching of a cue for such art-historical and critical meander of members' oeuvre especially on the inaugural show at NGMA, Bombay titled The Moderns curated by Yashodhara Dalmia in 1996.

Art historically Progressive Art Group has always remained as a bridge between avant garde and the emergent radical Indian Contemporary art of the fifties and sixties. The Group with Mulk Raj Anand as its resident spokesman has always been hailed as progenitor of Modern Art in India. Despite its vast contribution in the making of a language that marks the emergence of an Indian Modern in the sixties always remained a source of inspiration for later generation of artists. This revisit has been an overview of the repertoire especially their devoid of any meta-commentary till date on the basis of his public exhibitions and catalogues available and searching of a cue for such art-historical and critical meander of members' oeuvre especially on the inaugural show at NGMA, Bombay titled The Moderns curated by Yashodhara Dalmia in 1996.

The dialogue is a continuous process: it has little to do with past concepts of edification but emerges as a vital process, a landscape where we become familiar with the changes influencing our lives. Thus signals out how an eclectic range of imagery of a group of artists based in Bombay from the changing world of postcolonial India became instrumental in evolving a visual language of collage and citation, which in turn, acted as a vehicle of cultural force, creating and negotiating as the sacred, the erotic, the political, the modern and beyond. The very idea of historicizing which carried with it some peculiarly European assumptions of disenchanted space, secular time and human sovereignty now challenges the notion of our presence in the waiting rooms of metanarratives.

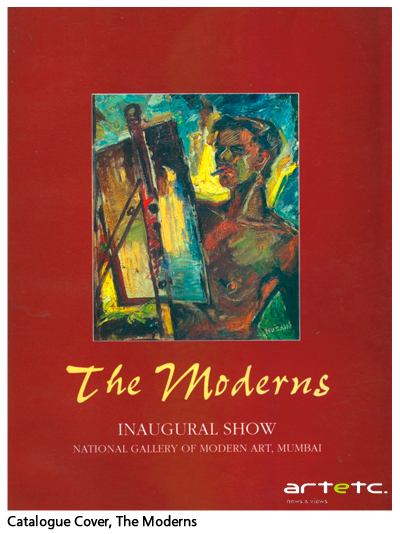

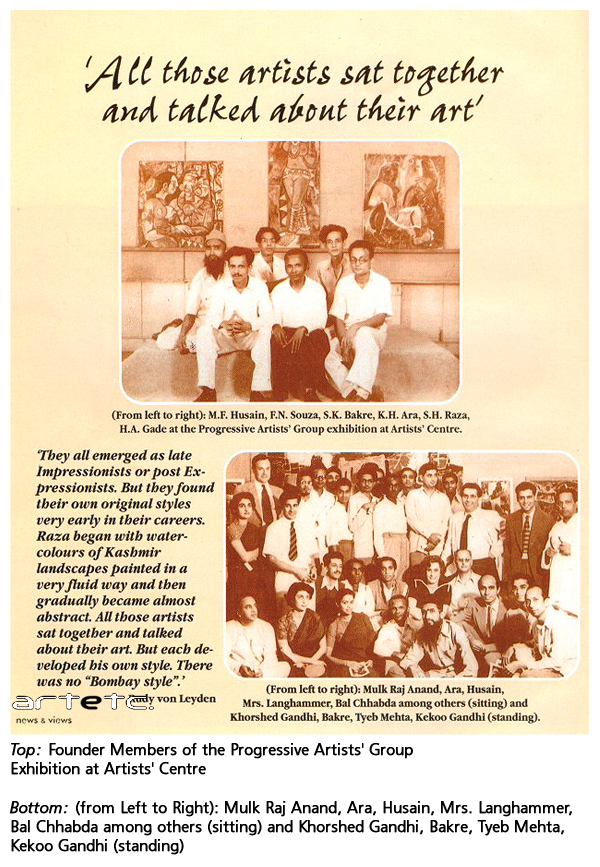

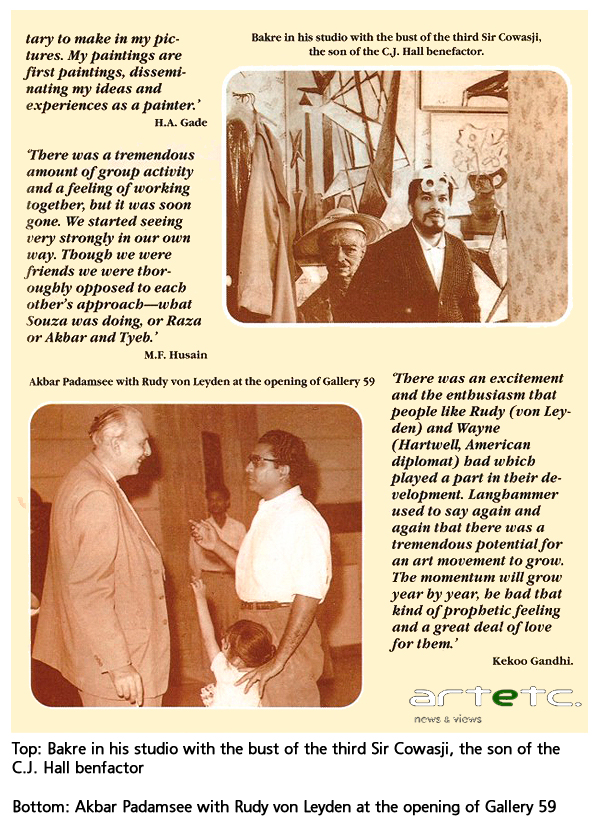

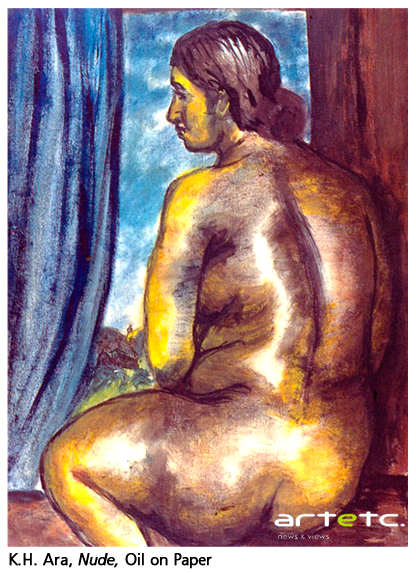

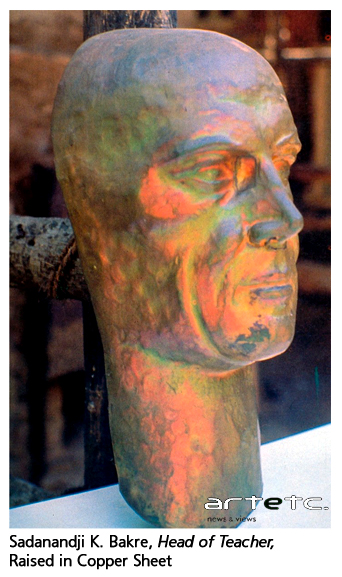

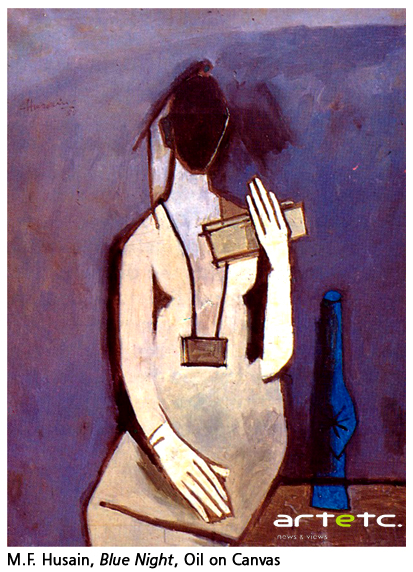

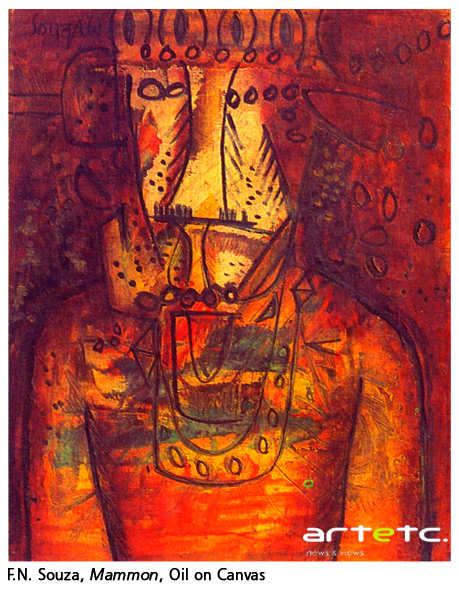

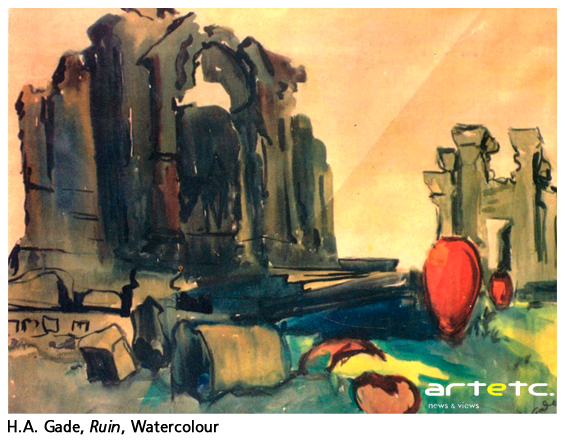

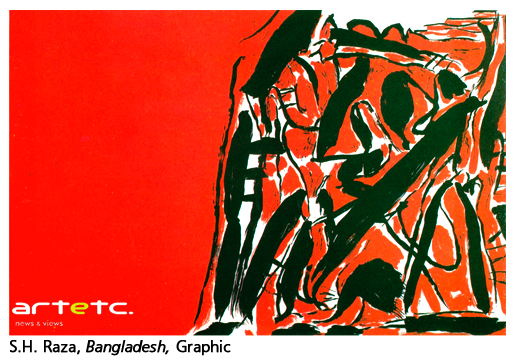

The C.J. Hall in south Bombay was the site of young pugilists to work out in the evenings. The crowds roar and applause a k.o with ferocity but that was the eighties. Till the fifties, the C. J. hall donated by philanthropist Sir Cowasji Jehangir where the National Gallery of Modern Art stands today was used for concerts, political meetings and sparse art activities and even weddings till the city fathers decided with determination and strong will protested against its further deterioration and decided to set up the Bombay chapter of National Gallery of Modern Art with objective of representing the evolution of the changing forms, acquiring and preserving works of art , organizing special exhibitions and developing an education and documentation centre , a reference library and for art education programmes. It opened with the show titled The Moderns: The Progressive Artists Group and its Associates curated by Yashodhara Dalmia. The group PAG consisted of M.F. Husain, F.N.Souza. S.K.Bakre. K.H.Ara, S.H.Raza, H.A.Gade and people like Ramkumar, V.S.Gaitonde, Bal Chhabda, Krishen Khanna, Akbar Padamsee, Tyeb Mehta were associated them later as a part of the extended circle. 'They all emerged as late impressionists or post expressionists. But they found their own styles very early in their careers. Raza began with water-colours of Kashmir landscapes painted in a very fluid way and then gradually became almost abstract. All those artists sat together and talked about their art. But each developed his own style. There was no 'Bombay style'- Rudy von Leyden.

The C.J. Hall in south Bombay was the site of young pugilists to work out in the evenings. The crowds roar and applause a k.o with ferocity but that was the eighties. Till the fifties, the C. J. hall donated by philanthropist Sir Cowasji Jehangir where the National Gallery of Modern Art stands today was used for concerts, political meetings and sparse art activities and even weddings till the city fathers decided with determination and strong will protested against its further deterioration and decided to set up the Bombay chapter of National Gallery of Modern Art with objective of representing the evolution of the changing forms, acquiring and preserving works of art , organizing special exhibitions and developing an education and documentation centre , a reference library and for art education programmes. It opened with the show titled The Moderns: The Progressive Artists Group and its Associates curated by Yashodhara Dalmia. The group PAG consisted of M.F. Husain, F.N.Souza. S.K.Bakre. K.H.Ara, S.H.Raza, H.A.Gade and people like Ramkumar, V.S.Gaitonde, Bal Chhabda, Krishen Khanna, Akbar Padamsee, Tyeb Mehta were associated them later as a part of the extended circle. 'They all emerged as late impressionists or post expressionists. But they found their own styles very early in their careers. Raza began with water-colours of Kashmir landscapes painted in a very fluid way and then gradually became almost abstract. All those artists sat together and talked about their art. But each developed his own style. There was no 'Bombay style'- Rudy von Leyden.

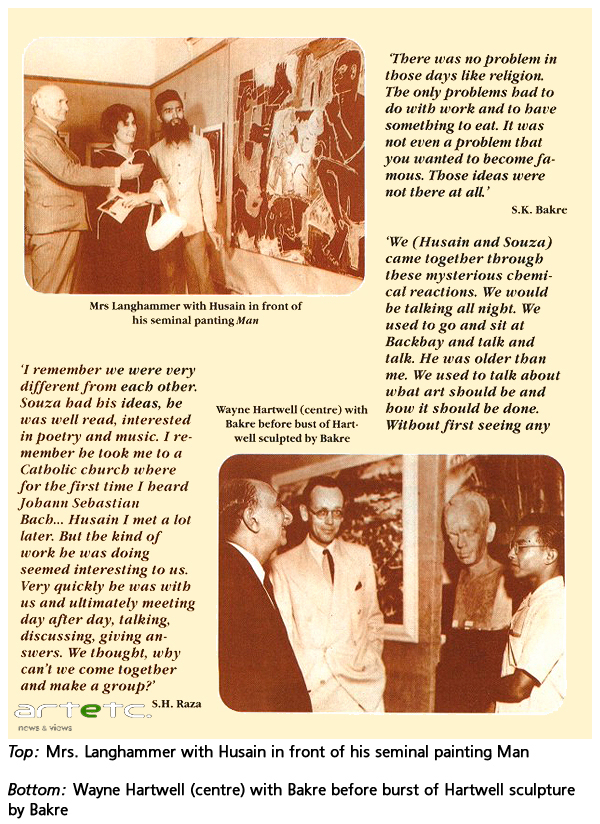

The rich and complex environment of the pre modern greatly eased the advent of modernism, but it also drew on another epochal development that pertained it to mature into a movement more substantial than a mere distraction of bored aesthetes. Climates, even emotional climates, change that our early modernists had its distinct history like all histories both internal and external. Today's art historians must move warily here while they revisit, for the laws of uneven development within and among societies defeat virtually every generalization. There was an excitement and the enthusiasm that people Rudy von Leyden and Wayne Hartwell, American diplomat had which played a part in their development. “Langhammer used to say again and again that there was a tremendous potential for an art movement to grow. The momentum will grow year by year, he had that kind of prophetic feeling and a great deal of love for them “- Kekoo Gandhy. As early as 1945, Kekoo Gandhy provided changing space for the paintings in the Chemould framing shop which was later to become an art gallery. S.K.Bakre reminisces in the catalogue- “There was no problem in those days like religion. The only problems had to do with work and to have something to eat. It was not even a problem that you wanted to become famous. Those ideas were not there at all.”

The rich and complex environment of the pre modern greatly eased the advent of modernism, but it also drew on another epochal development that pertained it to mature into a movement more substantial than a mere distraction of bored aesthetes. Climates, even emotional climates, change that our early modernists had its distinct history like all histories both internal and external. Today's art historians must move warily here while they revisit, for the laws of uneven development within and among societies defeat virtually every generalization. There was an excitement and the enthusiasm that people Rudy von Leyden and Wayne Hartwell, American diplomat had which played a part in their development. “Langhammer used to say again and again that there was a tremendous potential for an art movement to grow. The momentum will grow year by year, he had that kind of prophetic feeling and a great deal of love for them “- Kekoo Gandhy. As early as 1945, Kekoo Gandhy provided changing space for the paintings in the Chemould framing shop which was later to become an art gallery. S.K.Bakre reminisces in the catalogue- “There was no problem in those days like religion. The only problems had to do with work and to have something to eat. It was not even a problem that you wanted to become famous. Those ideas were not there at all.”

“The presence of certain Europeans at this juncture proved to be crucial for bringing about an art consciousness”, writes Dalmia. Walter Langhammer, the art director of the Times of India had left Vienna with his wife after the Nazi invasion and reached India in1938. Rudy von Leyden, the art critic of the times of India, who had arrived from Germany in the early thirties, provided constructive criticism in those times. He was known to cycle down to the press after the opening of a show so that he could write the review on the same day. Leyden said, “Till that time a staff reporter used to be sent to cover art shows and he would make a routine report saying so and painted a cow in the garden or whatever I think the review and the talk about art, the war effort, the one- man shows all came together and stimulated a new atmosphere.” A shifting weave of memory takes place, gaze that is intimate and penetrating. Texture is an important attribute in these works of ten artists that is achieved through intricate dividing and layering of the ground. The patterning of separate areas sets off these spaces giving each its own depth and providing body to the visual text. The images and sculptures stem from their environment. These come to them in the way of revelation- the specific context in which one would limit and define their significance. Considered or hieratic, all these six artists along with its associates almost arresting each has its own story to tell; one face seems shadowed with reverie animated with varied layers of slips and glazes. “I remember we were very different from each other. Souza had his ideas, he was well read, interested in poetry and music. I remember he took me to a Catholic Church where for the first time I heard Johann Sebastian Bach… Husain I met a lot later. But the kind of work he was doing seemed interesting to us. Very quickly he was with us and ultimately meeting day after day, talking, discussing, giving answers. We thought why can't we come together and make a group?”- (S. H. Raza). The ensemble and paintings of the members have an opulent materiality even today that convinces sheerly based on its energy and subtle text and has the wheels of memory to make fitful revolutions. The narratives are inescapable, constantly intersecting our lives and minds, and produce powerful effects on the viewers. We share with them their view of a fluid, impermanent reality and this time besmeared with expressionistic brushwork and inscriptions in bronze and others that is much freer and bears a strong personal identity.

“The presence of certain Europeans at this juncture proved to be crucial for bringing about an art consciousness”, writes Dalmia. Walter Langhammer, the art director of the Times of India had left Vienna with his wife after the Nazi invasion and reached India in1938. Rudy von Leyden, the art critic of the times of India, who had arrived from Germany in the early thirties, provided constructive criticism in those times. He was known to cycle down to the press after the opening of a show so that he could write the review on the same day. Leyden said, “Till that time a staff reporter used to be sent to cover art shows and he would make a routine report saying so and painted a cow in the garden or whatever I think the review and the talk about art, the war effort, the one- man shows all came together and stimulated a new atmosphere.” A shifting weave of memory takes place, gaze that is intimate and penetrating. Texture is an important attribute in these works of ten artists that is achieved through intricate dividing and layering of the ground. The patterning of separate areas sets off these spaces giving each its own depth and providing body to the visual text. The images and sculptures stem from their environment. These come to them in the way of revelation- the specific context in which one would limit and define their significance. Considered or hieratic, all these six artists along with its associates almost arresting each has its own story to tell; one face seems shadowed with reverie animated with varied layers of slips and glazes. “I remember we were very different from each other. Souza had his ideas, he was well read, interested in poetry and music. I remember he took me to a Catholic Church where for the first time I heard Johann Sebastian Bach… Husain I met a lot later. But the kind of work he was doing seemed interesting to us. Very quickly he was with us and ultimately meeting day after day, talking, discussing, giving answers. We thought why can't we come together and make a group?”- (S. H. Raza). The ensemble and paintings of the members have an opulent materiality even today that convinces sheerly based on its energy and subtle text and has the wheels of memory to make fitful revolutions. The narratives are inescapable, constantly intersecting our lives and minds, and produce powerful effects on the viewers. We share with them their view of a fluid, impermanent reality and this time besmeared with expressionistic brushwork and inscriptions in bronze and others that is much freer and bears a strong personal identity.

To talk about specific genres, we somewhat stumble upon some other kind of difficulty here for any foreclosure to it has already proven disastrous and an incomplete study. In the fractured times after independence, an entire generation of feisty, anxious and aspirational artists came into their own in a heroic attempt to find a voice. How do we account for the uncritical rather intent reading of these works into categories as belated, ahistorical and unoriginal- are we in urgent need of a critical apparatus, one capable of reinventing the possibility of a meaningful engagement with the ambivalent works of this complex generation- post independence, postcolonial. “I have come to believe that pictorial truth is a self-contained phenomenon within the limits of the medium and visual imagery is only a means to arrive at this truth. Therefore, I have no story to tell. No literary message to give, no social commentary to make in my pictures. My paintings, disseminating my ideas and experiences as a painter”- (H. A. Gade). It is hardly surprising that the character of our art practice during the first 100 years of art colleges' existence was largely shaped by the conventions of English art. Even the periods of pronounced nationalist fervour, particularly the late 19th and early 20th century and again in the immediate post-independence era of the 1940's and fifties may have quelled , but did not diminish the strangle-hold which the British academic tradition continued to exert and the anxiety to look up to the West, especially in art colleges, well into the 1960's the nature of Indian response to European modernism are pronounced just because early modernism was brought here by artists who had gained their experience of it through London and France, and only to a lesser extent through New York. It existed, however skeptically, as part of an internationally fluid scheme of ideas and interventions. Having wavered in their affiliation and with the emergence of International Abstraction in the fifties and sixties the relationship was changed but surprisingly, not severed. Although the momentum for this new art derived from New York, it was the experience of it gained through London and Paris proved significant to some of us. But at the same time, the absence of a predominant international art centre and the criticism for being an appendage of the West coincided with the growth of a regional impetus in contemporary art, which altered, as a matter of course, the relationship between the two worlds. In the field of art criticism, in reaction against the glut of turgid subjective and poetic analysis of content, critics for example, Clement Greenberg, whose formalist approach dominated art criticism during the sixties, dismissed all such analysis as irrelevant. His influence was pronounced in our art writings of that period. In the name of objectivity, they insisted on dealing exclusively with the formal components of art. Inquiry into issues external to art was condemned. But in the following decade, the formalist approach lost its sway over to art discourse. Critics in increasing numbers and with growing confidence have been investigating extra-aesthetic feelings and thoughts in here in the physical properties of works of art. Though, everyone is aware of the intentional fallacy, that an artist's intention is not necessarily conveyed by his or her works, critics are also looking into artist's own statements for suggestions. This idea that these artists were thrown into the middle of whole process of art making is a revolutionary idea- a critique of modernism. “There was a tremendous amount of group activity and a feeling of working together, but it was soon gone. We started seeing very strongly in our own way. Though we were friends we were thoroughly opposed to each other's approach- what Souza was doing , or Raza or Akbar and Tyeb”- (M.F.Husain). The artists claimed they were inventing modernism for India. They do not begin at the beginning or end at the end. Instead of drawing out the character on providing a catalogue on abstraction this essay mainly makes a selective attempt to re-embrace some of these artists that helped in producing a corpus of radical language in Indian Modern Art.

To talk about specific genres, we somewhat stumble upon some other kind of difficulty here for any foreclosure to it has already proven disastrous and an incomplete study. In the fractured times after independence, an entire generation of feisty, anxious and aspirational artists came into their own in a heroic attempt to find a voice. How do we account for the uncritical rather intent reading of these works into categories as belated, ahistorical and unoriginal- are we in urgent need of a critical apparatus, one capable of reinventing the possibility of a meaningful engagement with the ambivalent works of this complex generation- post independence, postcolonial. “I have come to believe that pictorial truth is a self-contained phenomenon within the limits of the medium and visual imagery is only a means to arrive at this truth. Therefore, I have no story to tell. No literary message to give, no social commentary to make in my pictures. My paintings, disseminating my ideas and experiences as a painter”- (H. A. Gade). It is hardly surprising that the character of our art practice during the first 100 years of art colleges' existence was largely shaped by the conventions of English art. Even the periods of pronounced nationalist fervour, particularly the late 19th and early 20th century and again in the immediate post-independence era of the 1940's and fifties may have quelled , but did not diminish the strangle-hold which the British academic tradition continued to exert and the anxiety to look up to the West, especially in art colleges, well into the 1960's the nature of Indian response to European modernism are pronounced just because early modernism was brought here by artists who had gained their experience of it through London and France, and only to a lesser extent through New York. It existed, however skeptically, as part of an internationally fluid scheme of ideas and interventions. Having wavered in their affiliation and with the emergence of International Abstraction in the fifties and sixties the relationship was changed but surprisingly, not severed. Although the momentum for this new art derived from New York, it was the experience of it gained through London and Paris proved significant to some of us. But at the same time, the absence of a predominant international art centre and the criticism for being an appendage of the West coincided with the growth of a regional impetus in contemporary art, which altered, as a matter of course, the relationship between the two worlds. In the field of art criticism, in reaction against the glut of turgid subjective and poetic analysis of content, critics for example, Clement Greenberg, whose formalist approach dominated art criticism during the sixties, dismissed all such analysis as irrelevant. His influence was pronounced in our art writings of that period. In the name of objectivity, they insisted on dealing exclusively with the formal components of art. Inquiry into issues external to art was condemned. But in the following decade, the formalist approach lost its sway over to art discourse. Critics in increasing numbers and with growing confidence have been investigating extra-aesthetic feelings and thoughts in here in the physical properties of works of art. Though, everyone is aware of the intentional fallacy, that an artist's intention is not necessarily conveyed by his or her works, critics are also looking into artist's own statements for suggestions. This idea that these artists were thrown into the middle of whole process of art making is a revolutionary idea- a critique of modernism. “There was a tremendous amount of group activity and a feeling of working together, but it was soon gone. We started seeing very strongly in our own way. Though we were friends we were thoroughly opposed to each other's approach- what Souza was doing , or Raza or Akbar and Tyeb”- (M.F.Husain). The artists claimed they were inventing modernism for India. They do not begin at the beginning or end at the end. Instead of drawing out the character on providing a catalogue on abstraction this essay mainly makes a selective attempt to re-embrace some of these artists that helped in producing a corpus of radical language in Indian Modern Art.

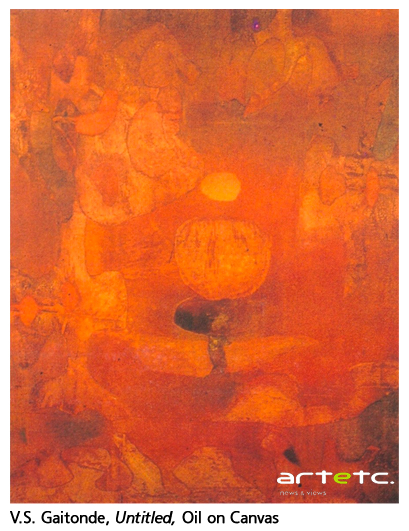

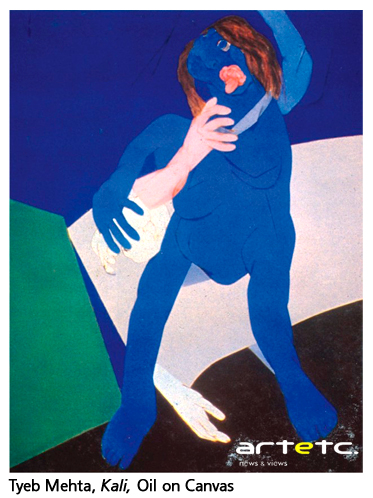

Let us now look at the body of work by two distinguished members of Progressive Artists Group (PAG) formed in the year India gained Independence. The artists lived in small congested spaces and traveled long distances to meet at Chetana restaurant or the Bombay Art Society or by the sea at Marine Drive and at Rampart Row. “The real common denominator for us was significant form. We were expressing ourselves differently, we had different visions during the early days but what was common was a search for significant. Each in his own way, according to his own vision” (-S.H. Raza). In V. S. Gaitonde's (1924- 2001 ) work, who joined the group few years later; meditative silence that culminates from lush amalgamations of restless lines that seduce atmospheric fields, and framing edges to define a somewhat unreal space that is temporarily free from inane strictures. In her essay on the Group PAG for the show at NGMA in 1996 that marked the opening of its Bombay chapter, Yashodhara Dalmia writes 'a strong abstractionist, V.S. Gaitonde transformed early landscape painting into works of great lyric transcendence'. Tyeb Mehta, who was a close of his observes, “There was something about Gaitonde's work- of course he was very much influenced by Klee- it was very imaginative and poetic. He did figurative work earlier but soon turned to abstraction. He was very close to Palsikar and Mohan Samant- technically, not image wise. They created their own colour by rubbing cowrie shell on colour into another and create unbelievable texture and colour nuances. This was a technique developed by Palsikar”. Gaitonde's colour surfaces are translucent creating almost an underwater ambience with beams of light penetrating the depths. Even the red of his work gets transmuted into light leading to an almost spiritual sublimation. The linear elements run back and forth between these two masses, and occasionally establish distant satellite areas at the end of their sweep. Despite his direct address and immediacy of marking however Gaitonde's work creates a meditative, and sometimes luscious, atmospheric depth that draws the viewer in. Here, accumulating, linear density is reminiscent of the anxious scrawls that seem to be both forming and yet so tormenting and eating away the drawings churn with the rain, stream and speed whose forms are emerging and dissolving in mist and light and dynamism that constitute an internal landscape. The search is spontaneous and a bodying forth of feeling delivering the pleasures of traditional gestural abstraction in a personal or expressive idiom, which is particularly his genius. The vernacular alphabets, the thin lines not too long and calculated to record any single, sweeping movement of the artist's arm, replace spontaneity with the conscious manipulation of its evidence.

Let us now look at the body of work by two distinguished members of Progressive Artists Group (PAG) formed in the year India gained Independence. The artists lived in small congested spaces and traveled long distances to meet at Chetana restaurant or the Bombay Art Society or by the sea at Marine Drive and at Rampart Row. “The real common denominator for us was significant form. We were expressing ourselves differently, we had different visions during the early days but what was common was a search for significant. Each in his own way, according to his own vision” (-S.H. Raza). In V. S. Gaitonde's (1924- 2001 ) work, who joined the group few years later; meditative silence that culminates from lush amalgamations of restless lines that seduce atmospheric fields, and framing edges to define a somewhat unreal space that is temporarily free from inane strictures. In her essay on the Group PAG for the show at NGMA in 1996 that marked the opening of its Bombay chapter, Yashodhara Dalmia writes 'a strong abstractionist, V.S. Gaitonde transformed early landscape painting into works of great lyric transcendence'. Tyeb Mehta, who was a close of his observes, “There was something about Gaitonde's work- of course he was very much influenced by Klee- it was very imaginative and poetic. He did figurative work earlier but soon turned to abstraction. He was very close to Palsikar and Mohan Samant- technically, not image wise. They created their own colour by rubbing cowrie shell on colour into another and create unbelievable texture and colour nuances. This was a technique developed by Palsikar”. Gaitonde's colour surfaces are translucent creating almost an underwater ambience with beams of light penetrating the depths. Even the red of his work gets transmuted into light leading to an almost spiritual sublimation. The linear elements run back and forth between these two masses, and occasionally establish distant satellite areas at the end of their sweep. Despite his direct address and immediacy of marking however Gaitonde's work creates a meditative, and sometimes luscious, atmospheric depth that draws the viewer in. Here, accumulating, linear density is reminiscent of the anxious scrawls that seem to be both forming and yet so tormenting and eating away the drawings churn with the rain, stream and speed whose forms are emerging and dissolving in mist and light and dynamism that constitute an internal landscape. The search is spontaneous and a bodying forth of feeling delivering the pleasures of traditional gestural abstraction in a personal or expressive idiom, which is particularly his genius. The vernacular alphabets, the thin lines not too long and calculated to record any single, sweeping movement of the artist's arm, replace spontaneity with the conscious manipulation of its evidence.

S. H Raza (born 1924) aims at pure plastic order, form order and concerns the theme of nature. As a counterpoint to the figurists who began as a landscape artist and progressively turned more and more towards abstract. Both have converged into a single point and become inseparable; the point, the bindu- symbolizes the seed, bearing the potential of all life, in a sense to express this concept, Raza resorts to the principles which govern his abstraction. The marks of edge, tradition and handling become part of the living image. So do the measures taken to retard, decay and fend off damage; his abstraction implores us to look at the rest of painting as if it were abstract.

Now the novelty of these exciting and powerful artists of PAG born precisely of this articulation which considers them together, and the triple practice conjugating questions of various orders, a treat to watch them work in this perspective gives a specific turn to the problematic in so far as it is indissociable from those beyond art. The images or the visual texts that mediate through our own experience we jealously guard and with skills we guard our symptoms. They are something we wish to give for they speak our desire. But the same desire may find other forms of representation and interrogates painterly values at the same time. The beauty and idea of these works hold us in extreme promises to challenge representation as “formidable tool of domination” but to a redefinition of a visual text because it's high time to realize we will no more be restricted by debased modernism and redefine the definition, of realism, abstraction and cultural representation as Dalmia sums up her catalogue essay beautifully. “As the narrative of the Progressive Artists unfolds, there is a dawning realization that to progress is to constantly struggle and having achieved the form to search once again for renewal.”