- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- The Enigma That was Souza

- Progressive Art Group Show: The Moderns

- The Souza Magic

- M.F. Husain: Other Identities

- From All, One; And From One, All

- Tyeb Mehta

- Akbar Padamsee: The Shastra of Art

- Sensuous Preoccupations of V.S. Gaitonde

- Manishi Dey: The Elusive Bohemian

- Krishen Khanna: The Fauvist Progressive

- Ram Kumar: Artistic Intensity of an Ascetic

- The Unspoken Histories and Fragment: Bal Chhabda

- P. A. G. and the Role of the Critics

- Group 1890: An Antidote for the Progressives?

- The Subversive Modernist: K.K.Hebbar

- Challenging Conventional Perceptions of African Art

- 40 Striking Indian Sculptures at Peabody Essex Museum

- Tibetan Narrative Paintings at Rubin Museum

- Two New Galleries for the Art of Asia opens at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

- Raphael, Botticelli and Titian at the National Gallery of Australia

- The Economics of Patronization

- And Then There Was Zhang and Qi

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Random Strokes

- Yinka Shonibare: Lavishly Clothing the Somber History

- A Majestic “Africa”: El Anatsui's Wall Hangings

- The Idea of Art, Participation and Change in Pistoletto’s Work

- On Wings of Sculpted Fantasies

- The Odysseus Journey into Time in the Form of Art

- On Confirming the Aesthetic of Spectacle: Vidya Kamat at the Guild Mumbai

- Dhiraj Choudhury: Artist in Platinum Mode

- Emerging from the Womb of Consciousness

- Gary Hume - The Indifferent Owl at the White Cube, London

- Daum Nancy: A Brief History

- Experimenting with New Spatial Concepts – The Serpentine Gallery Pavilion Project

- A Rare Joie De Vivre!

- Art Events Kolkata-December 2011– January 2012

- Art Bengaluru

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Delhi Dias

- Musings from Chennai

- Preview, February, 2012- March, 2012

- In the News-January 2012

ART news & views

The Subversive Modernist: K.K.Hebbar

Issue No: 25 Month: 2 Year: 2012

by H.A. Anil Kumar

Though K. K. Hebbar was not represented in the modern Indian art historical context, he was revered in Karnataka. He was not seen in the same light as his contemporaries for many reasons: Hebbar was contextualized as a regional figure and often never mentioned. A ‘monolithic history’ of modernism was written by tracking the trajectories of avant- garde artist movements, manifestos and path breakers. Many artists were thus overlooked and grouped together to represent a period in art history. Hebbar was reluctant to be a part of the historical Progressive Artists Group. He was not seen as radical or political, but was clubbed along with other contemporaries of the Progressive Artists Group in the milieu of Mumbai. Yet, his work fits into the manifesto of the Progressive agenda of ‘aesthetic order, plastic coordination and colour combination’.

Though K. K. Hebbar was not represented in the modern Indian art historical context, he was revered in Karnataka. He was not seen in the same light as his contemporaries for many reasons: Hebbar was contextualized as a regional figure and often never mentioned. A ‘monolithic history’ of modernism was written by tracking the trajectories of avant- garde artist movements, manifestos and path breakers. Many artists were thus overlooked and grouped together to represent a period in art history. Hebbar was reluctant to be a part of the historical Progressive Artists Group. He was not seen as radical or political, but was clubbed along with other contemporaries of the Progressive Artists Group in the milieu of Mumbai. Yet, his work fits into the manifesto of the Progressive agenda of ‘aesthetic order, plastic coordination and colour combination’.

–Suresh Jayaram (in his lecture The Reluctant Modernist: K.K.Hebbar 1911-1996) at 1Shanthiroad, in view of the first retrospective of K.K.Hebbar that was held at the NGMA Bengaluru between August 21-October 20, 2011.

(I)

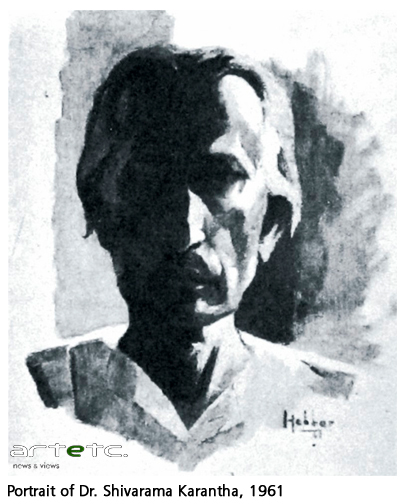

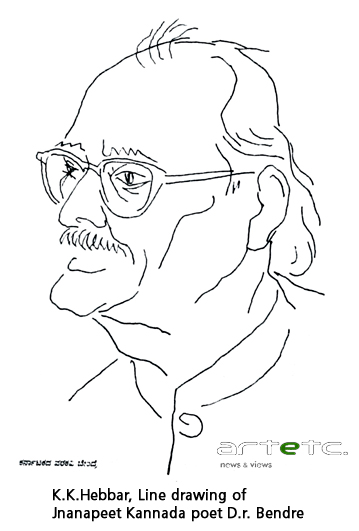

When he wrote a letter to Seshagiri Rao (6-9-1978),1 the Kannada writer who was editing a volume celebrating the 77th birthday of the Jnanapeet awardee Dr. Shivarama Karantha, Hebbar had attested a drawing alongside, instead of an article, with a verbal justification to prove that he was a man of lines, not words. Hebbar’s dilemma between words and images—interrelated through ‘lines’ for which he is so famously known for, finds exemplary representation in the writings ‘by’ and ‘about’ him, in a language other English (necessarily Kannada). In other words, what comes through literary representations and communication about Hebbar in Kannada is a lost premise to those who have already judicially categorized him--as Suresh points out--based on the available sources about him in Indian English. Before continuing with this dimension that makes Hebbar the artist he is, a closer look at this letter and the related matter is of utmost importance.

When he wrote a letter to Seshagiri Rao (6-9-1978),1 the Kannada writer who was editing a volume celebrating the 77th birthday of the Jnanapeet awardee Dr. Shivarama Karantha, Hebbar had attested a drawing alongside, instead of an article, with a verbal justification to prove that he was a man of lines, not words. Hebbar’s dilemma between words and images—interrelated through ‘lines’ for which he is so famously known for, finds exemplary representation in the writings ‘by’ and ‘about’ him, in a language other English (necessarily Kannada). In other words, what comes through literary representations and communication about Hebbar in Kannada is a lost premise to those who have already judicially categorized him--as Suresh points out--based on the available sources about him in Indian English. Before continuing with this dimension that makes Hebbar the artist he is, a closer look at this letter and the related matter is of utmost importance.

In this particular letter consisting of about ten sentences, the artist spends almost half of it to appreciate the contribution of Karantha’s book Kalaajagattu2 on visual pedagogy through Kannada language. In the rest of the text, he (Hebbar) expresses his inability and inexperience to write in Kannada (his mother tongue) in particular! On a larger and general note, it is to be observed that arguably whenever Indian artists have insisted upon the unnecessary burden of verbalizing their art, it is about the regional Indian languages that they are referring to, from within which they would have had evolved, with an ounce of pronounced silence about the advantages that English hold together for them.

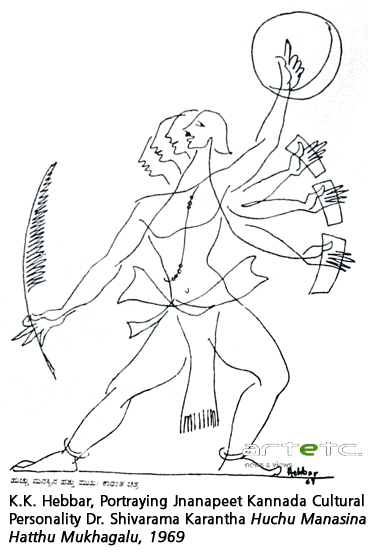

Also Hebbar notes that since writing is not his media of expression he urges the editor to instead print the drawing he has created, depicting the multi-facetedness of Karantha, the litterateur who was a painter, art critic, art historian among doing many other things. In other words, Hebbar, through this letter, declines an opportunity to get influenced from a model set by his friend who had shown the path to cross over between two disciplines—the visual and the verbal. Lines, for Hebbar, were analogous to what all those creative fields that Karantha indulged in.

Also Hebbar notes that since writing is not his media of expression he urges the editor to instead print the drawing he has created, depicting the multi-facetedness of Karantha, the litterateur who was a painter, art critic, art historian among doing many other things. In other words, Hebbar, through this letter, declines an opportunity to get influenced from a model set by his friend who had shown the path to cross over between two disciplines—the visual and the verbal. Lines, for Hebbar, were analogous to what all those creative fields that Karantha indulged in.

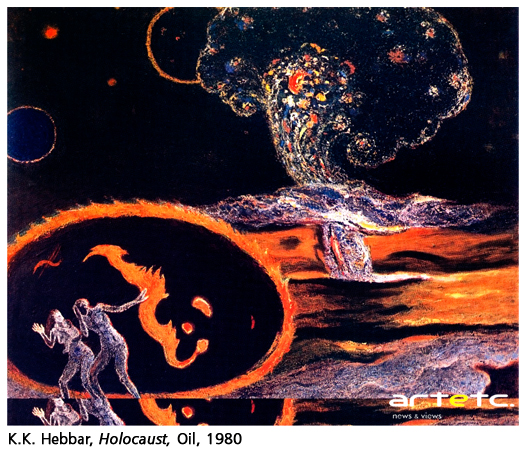

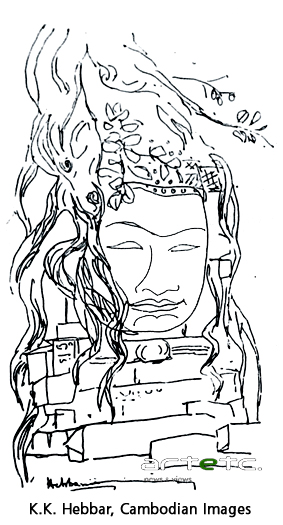

Here is a strong indication that though, as Suresh Jayaram argues, Hebbar’s recognition as a (Karnataka) State champion was more genuine than his position within a ‘national art premise’, his association with the ‘dancing and singing’ lines, his speeches, writings (in English) and his attitude towards Kannada presents not a straightforward but a sophisticated mind of an artist, which is yet unavailable to the English-speaking nationalistic discourse of Indian visual art, by and large. Institutionalizing Hebbar through an official museum for him by the State, and a wide recognition of his ‘performative’ lines as against his painterliness3 justifies the fact that Hebbar’s ability for linear representation, over his painterliness, is the offshoot of the reluctant writer within him. In a way, his friendship and analogies with writers like Shivarama Karantha, Vyasaraya Ballala and Yashavantha Chittala finds no parallel with other co-artists. The best of Hebbar’s representations, within the linearity, was what he was trying to translate into coloured lines, which seemed like coloured strokes and lines of shorter lengths, fragmentary views (like in his painting Goa) of kaleidoscopic formats. In other words, in the late 70s onwards his paintings were transliteration of what linearity meant to him in colours. Hence his paintings created after 1970s in particular, is in agreement of two aspects that are of utmost importance to Indian modernism in visual culture:

That his split-identity as a nationalist artist and a regional artist, that are at loggerheads with each other, are analogous to his ‘transformed linearity through painterly renderings’;4 and

The ambiguity that is assigned to his talent as a ‘linear artist’ as against his painterly works—are both products of the political ambiguity of the new nation during the days when he was emerging as a redemptive Modernist. Hebbar’s very insistence of being possessed with unique linear ability was (i) an attempt to endorse his paintings as coloured lines, (ii) to appropriate lines from its subversive characteristics status; and also (iii) to indicate the negotiative ability of the country, recently de-colonized, coming to terms with its new found independence and finally, (iv) the addressal of the question as to what to do with the new found political as well as aesthetic freedom.5 The Moderates in Congress, the middle class of India, the art movies and the line drawings of Hebbar share a lot of similarities of low mimesis, in the light of extremist urban, bourgeoisie, large scaled and loud imageries that many of his contemporaries produced.

In an earlier letter written three years before (30.11.1975),6 in response to Martha Aston, the tone is that of a ‘reserved’ Hebbar. Martha, who would have by then criticized Shivarama Karantha’s experiments in Yakshagana on the grounds of being anti-tradition, had later written to Hebbar enquiring as to whether she could meet him--the friend of Karantha, in the light of this criticism. Hebbar invites her saying that ‘everybody’s opinion is to his/her own self’. However, the tone of the letter proves that Marta’s fear of being admonished by the artist is true. The artist’s creative dilemma between words and lines not only exemplifies the ‘reluctant Modernist’ within him but also as a ‘subversive Modernist’. His line drawings and verbal withdrawal seem to be a reactionary gesture towards what was happening to t he lives, works, recognition and popularity of his close contemporaries like M.F. Husain, Ara, Raza and Souza. On the other hand, the visual language at the turn of the independence, owing to the new market forces in the new metropolis like Bombay, still held the linearity and lines as subversive to the painterliness. And it is no mere coincidence that the palette of Hebbar’s urban contemporary Modernists were vivid and brighter in relation (and comparison) to the pre-independent Bengal Renaissance artworks.

he lives, works, recognition and popularity of his close contemporaries like M.F. Husain, Ara, Raza and Souza. On the other hand, the visual language at the turn of the independence, owing to the new market forces in the new metropolis like Bombay, still held the linearity and lines as subversive to the painterliness. And it is no mere coincidence that the palette of Hebbar’s urban contemporary Modernists were vivid and brighter in relation (and comparison) to the pre-independent Bengal Renaissance artworks.

(II)

Almost half a century before the first letter (by Hebbar), K. Venkatappa, another artist hailing from Karnataka, had painted Mad After Veena (1920s) as a visual response to the letter that he received from his guru Abhanindranath Tagore, who admonished him for deviating away (into music) from what he had trained himself to be—a painter. Both the artists (K.K. Hebbar-1911-1996; and K. Venkatappa-1887-1965), with a difference of about two and a half decade in between, throughout and thoroughly argued for a sanctity of a certain pure visual language (as against and separate from the verbal) both before and after Indian political independence. Both (Hebbar and K.V) hailed from the same State, moved away from the place of both their ‘origin’ and ‘authority’ and both were hailed as State heroes as if to compensate a loss of a pan-Indian recognition for them!

It is not a mere coincidence that both of them (and only these two) have been officially museumised by the Government of Karnataka, that too in the same building! The administrative apparatus seem to have rendered a poetic justice to these two who pioneered in a marginal field within what is being defined as Kannada culture, which was/is otherwise by and large a verbal/oral-centric culture. Often the authority endorses what it seems to marginalize, as if by default and there lies the pleasure and prejudice of democracy! Hebbar, the subversive Modernist empowered lines and linearity to do more than and play many roles that other privileged media were supposed to do in general. Even when he painted, he was painting coloured lines! This he did because he saw these ‘acting and singing’ lines to be a spontaneous ammunition available for him against the aggression of the extremists, nationalists and the regional culturalists—all at the same.

(III)

(III)

There is no proof as to whether Venkatappa did write back to his guru’s grunting reply letter to the former’s painting-as-response, i.e. Mad After Veena. Hebbar’s drawing of Karantha’s multifacetedness was subsequently published in the compilation. Venkatappa’s diaries, like Hebbar’s letters and lectures (delivered on the subject ‘art education’ at Sir J.J.School of Arts-1957, a series of two lectures on visual arts at Mysore University—1969)7 clearly indicates these artists’ desire to demark spoken and written words as independent and different from visual arts and Hebbar’s faith in expressions beyond and away from any interactive ability inherent within them becomes obvious.

Ironically Hebbar, like K.Venkatappa, had no artist friends in Karnataka, while their acquaintance and admirers (respectively) with creative persons outside visual arts were in plenty. Both of them have not been placed into a mutual comparative premise by any theoretic discourse either in English or Kannada, until Karnataka Government’s authoritarian gesture to museumise both within a single museum premise. Hence their museums seem more like a collection rather than a museum, for the lack of any kind of information about them even to this day.8 The lack of a genuine discourse about these two artists seem to be a kind of poetic-justice and revenge to their apathy towards verbalization. Born in Karnataka, educated in CTI (Mysore), Dandavathimat’s ‘Nutan Kala Shale’ and then at J.J.School of Arts (both in Mumbai), settled in Mumbai for the best part of his professional life, Hebbar’s late emotional return to Karnataka was like the proverbial ‘return of the prodigal son’.

While Venkatappa’s diaries are to be found in the Vidhana Soudha archive, a kilometer behind the Venkatappa museum consisting of both his and Hebbar’s works, Hebbar’s letters and sample diary entries are to be found in the unknown and (if acknowledged) forgotten descriptive biographical book about him (in Kannada) by Ku.Shi.Haridasa Bhatta (1988, Regional Resources Centre for Folk Performing Arts, M.G.M.College, Udupi). Despite being associated with the Progressive Art Group of Mumbai, Hebbar did not initiate such and similar a movement to occur in the State from wherein he hails, while posthumously a museum and the first Retrospective has been conferred upon by the very State that he did not belong to wholeheartedly. It was left to R.M. Hadapad, the pioneer of modernist visual schooling in Karnataka (through his “We Four” artist group in 1968 and Ken School of Art, Bengaluru-1965) to initiate such a progressive movement down South. Hebbar contested the notion of belongingness, nationhood and this has been that strange premise of Diaspora which he championed. This, he did not only through his dancing and singing lines, but also through his autobiographical behaviour.

(IV)

(IV)

Positioning K.K. Hebbar with K. Venkatappa is in itself an intervention into the art historical operations in India whose focus has been upon groups, as against individuals; has been about those who are proximate to geo-political power structures rather than critical premises, in the absence of the latter as an independant agency, till date. Individualities and individual personalities of reluctant and subversive personalities within artistic groups and movements have always been dealt with harshly, by ignoring and silencing their contribution. If one can fill up the blank whose dots are represented by (i) English as Indian art historical language, (ii) prioritizing group contribution necessarily as against those of individuals, (iii) focus upon where the works end up rather than wherein they originate from; and similar such aspects, A new subversive Modernist Hebbar who was not a reluctant Modernist, would become obvious. The power of political subversion he brought to artistic groups’ representational politics through a bottle neck or single window called as ‘linearity’, that too during an age of political transformation of the biggest democracy of the world power, should in itself not be subverted anymore.

Reference

1.Read: page 166 in the book “Kattingeri Krishna Hebbar—Kale Mathu Baduku”, Ku.Shi.Haridasa Bhatta, published by The Regional Centre for Folk Performing Arts, M.G.M.College, Udupi, Karnataka, 1988.

2.Meaning ‘the world of art’ a la E.H.Gombrich’s ‘The Story of Art’. In fact the title of this art world encyclopedia by Shivarama Karantha is actually ‘Kala Prapancha’ and not ‘Kala Jagattu’, one of the very few books on art in Kannada, referred by art students in Karnataka art schools from past four decades.

3.Rosalyn D’Mello points out at the unevenness in Hebbar’s recent retrospective show at NGMA (New Delhi, which had earlier begun at Bengaluru NGMA a couple of months ago) and draws parallel with similar unevenness within the first retrospective of the same artist held in 1968, which the critic Richard Bartholomew had pointed out. Rosalyn says, “But Hebbar’s work comes across as mediocre, especially the semi-abstract works like ‘Energy’, ‘Jal’, and ‘Cosmos’ which are too literal in their conceptual framework”. Read: “The Curator Must Play Critic” by Rosalyn D’Mello, viewed on 16th December 2011.

4.For an elaboration of how Hebbar’s dual or split-identity contest each other and gave birth to an internal-Diasporic artist, Read: article: “Contesting National and the State: K.K.Hebbar’s Modernist Project” by H.A.Anil Kumar, artetc. news & views, Vol.3, No.6, 2011, Ed: R.Siva Kumar, http://www.artnewsnviews.com/articleid=383.

5.Read: Book: “K.K.Hebbar-Kale Mathu Baduku”, Ibid.

6.Ibid, page 164.

7.Page 186-188, 192-196, Ibid, Ku.Shi.Haridasa Bhatta.

8.Read: Article - “A Collection of Museums and a Museum for Collectors (Museum & Galleries at Chitrakala Parishath, Bangalore)”, June 2011, Vol.3, No.10, H.A.Anil Kumar, artetc. news & views. Also available online http://www.artnewsnviews.com/articleid =529.