- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- The Enigma That was Souza

- Progressive Art Group Show: The Moderns

- The Souza Magic

- M.F. Husain: Other Identities

- From All, One; And From One, All

- Tyeb Mehta

- Akbar Padamsee: The Shastra of Art

- Sensuous Preoccupations of V.S. Gaitonde

- Manishi Dey: The Elusive Bohemian

- Krishen Khanna: The Fauvist Progressive

- Ram Kumar: Artistic Intensity of an Ascetic

- The Unspoken Histories and Fragment: Bal Chhabda

- P. A. G. and the Role of the Critics

- Group 1890: An Antidote for the Progressives?

- The Subversive Modernist: K.K.Hebbar

- Challenging Conventional Perceptions of African Art

- 40 Striking Indian Sculptures at Peabody Essex Museum

- Tibetan Narrative Paintings at Rubin Museum

- Two New Galleries for the Art of Asia opens at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

- Raphael, Botticelli and Titian at the National Gallery of Australia

- The Economics of Patronization

- And Then There Was Zhang and Qi

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Random Strokes

- Yinka Shonibare: Lavishly Clothing the Somber History

- A Majestic “Africa”: El Anatsui's Wall Hangings

- The Idea of Art, Participation and Change in Pistoletto’s Work

- On Wings of Sculpted Fantasies

- The Odysseus Journey into Time in the Form of Art

- On Confirming the Aesthetic of Spectacle: Vidya Kamat at the Guild Mumbai

- Dhiraj Choudhury: Artist in Platinum Mode

- Emerging from the Womb of Consciousness

- Gary Hume - The Indifferent Owl at the White Cube, London

- Daum Nancy: A Brief History

- Experimenting with New Spatial Concepts – The Serpentine Gallery Pavilion Project

- A Rare Joie De Vivre!

- Art Events Kolkata-December 2011– January 2012

- Art Bengaluru

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Delhi Dias

- Musings from Chennai

- Preview, February, 2012- March, 2012

- In the News-January 2012

ART news & views

Ram Kumar: Artistic Intensity of an Ascetic

Issue No: 25 Month: 2 Year: 2012

by Seema Bawa

Ram Kumar is known as much for his reticence as his seminal influence on modern Indian art as the first important abstract painter of significance. Perhaps it is the enigma of his success; a triumph that certainly does not depend on public relation skills, his oratory and publicity stunts which fascinate people, his success is predicated upon the sheer silence that inhabits his canvases that force the viewers to sit up and take notice.

Sometimes his personal and artistic stillness can be disconcerting, but is always arresting. Almost two decades ago, I interviewed him during a Retrospective of his work held at the National Gallery of Modern Art, and again at more recent Retrospective. My memory of Ram Kumar is his hurrying away from the interview as soon as it was decently possible to touch up his older paintings that were showing the signs of age; worrying more about the presentation of his art than the projection of his artistic personality.

At parties and openings, Ram Kumar is the one always listening to stories, anecdotes and jokes, smiling shyly, maybe filing them away in his memory. He tells his stories through bold strokes on canvas: narratives that are not linear, one-dimensional or repetitive. The abstraction is deliberate and measured, not frenetic and wild, yet compelling one to read it, apply ones’ imagination to recreate the story of absent characters it tells. Initially he used his pen to tell these stories, and many of his short stories in Hindi were published and he even had brief stints as a journalist, and as a translator but his always in tandem with painting, finally parting ways with the written in favour of the visual world. Ram Kumar remains one of the best read painters and has a marked preference for art history by Anand Kentish Coomarswamy.

Art is indeed his vocation, for he read Economics at the Masters Level at St. Stephen’s college at Delhi, and received his training in art from Sailoz Mukherjee rather than a professional art institution. He gave up employment at a bank in 1948 to paint and learn about art and its practice through friends and master artists such as Raza in Mumbai and Andre Lhote and Fernand Leger in Paris. European post-war art and poetry of Jacques Dubois and Rouband, Neruda and others left a lasting impact on his consciousness. More than anything it was the pacificist peace movement that attracted him and he joined the French Communist Party and sought inspiration in the Social Realists such as Kathe and Fourgenon.

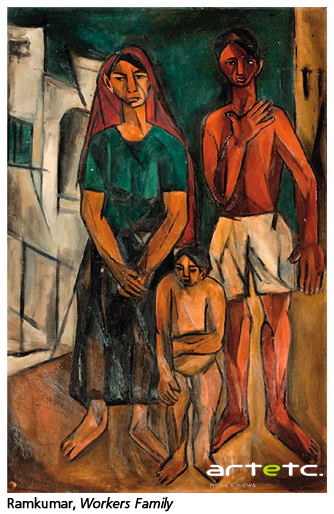

It is no wonder that Ram Kumar’s earliest works in the 1950’s privilege the world of the dispossessed refugees and laboring masses, the empty frontal gaze interrogating the viewer, demanding intervention and seeking solutions. His interaction with the displaced refugees in Karol Bagh in Delhi seeking a new beginning, trying to recover from the angst of separation and dislocation on the one hand and material deprivation on the other can be seen both in his writings and paintings.

The works from this period show the artist’s engagement with the lived world around him, confronting and reflecting the humanity in works such as the Workers Family. The dark planes and the reduced urban landscape in the background are in consonance with the contemporary art trends of the 1950’s. This was the same kind of modernism based on redefining the figure through deconstructing its form and composition that was being explored by many artist colleagues of the age, including Raza, Santosh, Husain and Krishen Khanna. But Kumar’s figures are all alone even in a group, there seems to be what the critics called ‘alienation’ and hopelessness. Of his figurative phase Ram Kumar’s late brother and eminent writer Nirmal Verma commented, “if Ram Kumar’s figures look so bereft, it is because they are bereft of all emotions, entirely de-emotionalized; frozen in their immobility they free us from within…and yet in their spirit and essence they look like some disfigured victims of an accident, an accident of catastrophic proportions about which we know nothing and of which they the victims themselves are unaware.”

The works from this period show the artist’s engagement with the lived world around him, confronting and reflecting the humanity in works such as the Workers Family. The dark planes and the reduced urban landscape in the background are in consonance with the contemporary art trends of the 1950’s. This was the same kind of modernism based on redefining the figure through deconstructing its form and composition that was being explored by many artist colleagues of the age, including Raza, Santosh, Husain and Krishen Khanna. But Kumar’s figures are all alone even in a group, there seems to be what the critics called ‘alienation’ and hopelessness. Of his figurative phase Ram Kumar’s late brother and eminent writer Nirmal Verma commented, “if Ram Kumar’s figures look so bereft, it is because they are bereft of all emotions, entirely de-emotionalized; frozen in their immobility they free us from within…and yet in their spirit and essence they look like some disfigured victims of an accident, an accident of catastrophic proportions about which we know nothing and of which they the victims themselves are unaware.”

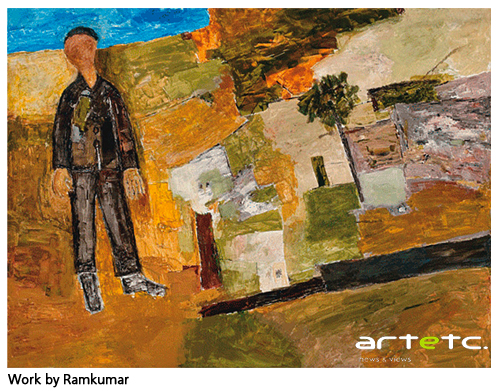

The artist Ram Kumar was one of the first amongst his contemporaries to give up the figurative in favour of the abstract. But for the artist ‘things did not change overnight. There were no major breaks where I said I won’t do it in this or that manner any more. It was more of a gradual evolution.” Even in his figurative as well as his early landscapes, inspired as they were, by Greece and the Himalayas, he played with absence, an absence that was presence-pregnant with meaning and resonating with ideas. Nirmal Verma says “the existential anguish, religious or aesthetic, is borne out of the encounter with-absence. Absence of god in the world or the world in the throes of the absence of meaning. Ram Kumar, as an artist, is not shocked or aggrieved by this absence, for he takes it as something naturally given, not as human deprivation but as a state of being.” He can partake of this absence and it is as if the muse of this absence usurps him during his creative process.

The figurative disappears from the canvas as the artist started exploring the human element through urban landscape of Benaras. He first visited Varanasi in 1960 where he sketched the Ghats of Ganga but without any people. It was as if he wanted to take us to a pristine space where pain and sufferings have a speaking presence. In Indian tradition Kashi, the city itself is the body of god, its topography- sacred and profane, providing the ultimate release and also the supreme bondage, moksha and kama both dwell in Kashi, as do dukha and its sublimation. Within this City of Light, Diana Eck reminds us “in the narrow lanes at the top of these steps moves the unceasing earthly drama of life and death, which Hindus call samsara. But here, from the perspective of the river, there is a vision of transcendence and liberation, which Hindus call moksha.”

Reminiscing about the initial experience of Benares, Ram Kumar says, “Benares is important for me both as an artist and as a human being, the first paintings came at a point when I wanted to develop elements in figurative painting and go beyond it, my first visit to the city invoked an emotional reaction as it had peculiar associations. But such romantic ideas were dispelled when I came face to face with reality. There was so much pain and sorrow of humanity. As an artist it became a challenge to portray this agony and suffering, its intensity required the use of symbolic motifs, so my Benares is of a representative sort.”

The river, ghats and the lanes that make up the physical and imagined religious landscape of the holy city gets translated into outlines set against swathes of coloured planes. In the earlier works there are some zones in white set against a dark reflecting river and a darker land mass with an occasional triangle in a doorway to suggest an icon. In his later series painted in two spates during the mid nineties and in then in 2007, the urban landscape with its structures, perhaps lodges, houses, temples and steps all jumbled together stand out against the blue river and sky. Though empty of human presence they resonate with the collective spiritual experience juxtaposed against the dark stark reality of the omnipresent death rituals. The mood of each painting is distinct; sometimes it is vibrant, at others somber and almost always sublime.

The artist in him continued to return to the mountains, as if reminded of his birthplace Shimla; transcending the internal and material cities to inhabit the natural and the primeval. Like a renunciator he returns to nature; from the nagara to the aranya, from the human, inhabited spaces to the forest to meditation and introspection, where there is the potential of thinking beyond the obvious, to delve into the essence of being. “I have never been and never will be completely abstract,” he emphasizes because for him “abstract is derived from nature. Take a part of a tree or a branch without its surroundings and it turns abstract.”

His visit to Ladakh is recorded in some of the most effective representations of a hostile environment sheltering the world’s most amazing geological formations. These lend themselves seamlessly to Ram Kumar’s austere temperament. The juxtaposition of triangular and horizontal planes in composite colours set against an azure blue sky creates looming stories. The Thar Desert has a similar effect on him and he paints the dry, arid landscape with vigorous strokes and strong colours.

The lack of the human does not mean a refusal to engage with the world. Indeed his abstractions are a sort of a reaction to the human condition in a different way. According to Nirmal Verma, “so if there is anything spiritual in Ram Kumar’s post Varanasi, it lies not in his acceptance of any metaphysical code or some supernatural belief, it lies in the spirit of acceptance itself…for acceptance has been part of his temperament as a man as well as his sensibility as an artist.”

.jpg) Of the post 1969 period, after the first encounter with Varanasi he says “my forms are as obscure as possible, sometimes more suggestive, sometimes less.” There is a lyricism in this absence and reticence that can be seen in his works from the 1980’s where overt referentiality gives way to abstract structures in ochre, yellows, rusts interspersed with deep ultramarine blue. The application of thick colours with palette knife using bold strokes is mesmerizing. The layering of colour speaks of alienation, violence and destruction. Later landscapes have an aura of meditative serenity and calm. The green of forests and the violets of mountains are mixed with the ambiguity of sienna and umbers. They seek creation and regeneration within the notional real topographies. This impetus towards more non representative forms of paintings came when, as he puts it, “he could see no meaning in painting street scenes as streets, trees as trees and rivers as rivers.”

Of the post 1969 period, after the first encounter with Varanasi he says “my forms are as obscure as possible, sometimes more suggestive, sometimes less.” There is a lyricism in this absence and reticence that can be seen in his works from the 1980’s where overt referentiality gives way to abstract structures in ochre, yellows, rusts interspersed with deep ultramarine blue. The application of thick colours with palette knife using bold strokes is mesmerizing. The layering of colour speaks of alienation, violence and destruction. Later landscapes have an aura of meditative serenity and calm. The green of forests and the violets of mountains are mixed with the ambiguity of sienna and umbers. They seek creation and regeneration within the notional real topographies. This impetus towards more non representative forms of paintings came when, as he puts it, “he could see no meaning in painting street scenes as streets, trees as trees and rivers as rivers.”

Referential or otherwise, Ram Kumar’s engagement with art at its most basic level, through colour and texture, through surface and depth, through meaning and its sattva or essence remains true and pure. It speaks of memory, of sacredness, of silence and stillness and yet provokes one to seek its source.

Reference

1. Seema Bawa, ‘In a Language of his Own’ in the Pioneer, November 23, 1993

2. Ram Kumar; A Retrospective, National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi, 1993

3. Ram Kumar, Vadehra Art Gallery, New Delhi 2007

4. Diana l Eck, Banaras: City of Light, Penguin Books, New Delhi, 1983.