- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

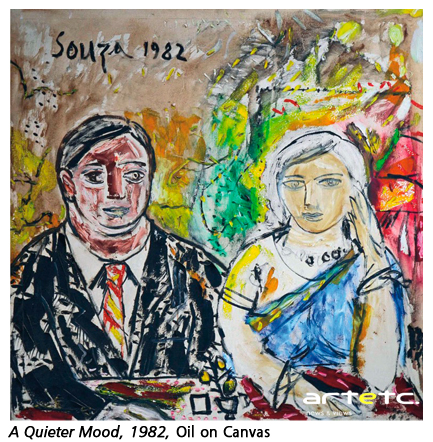

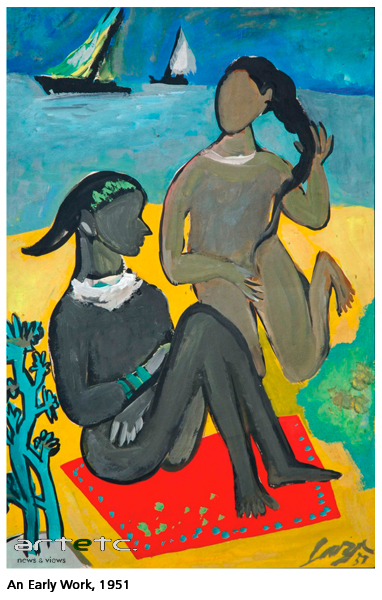

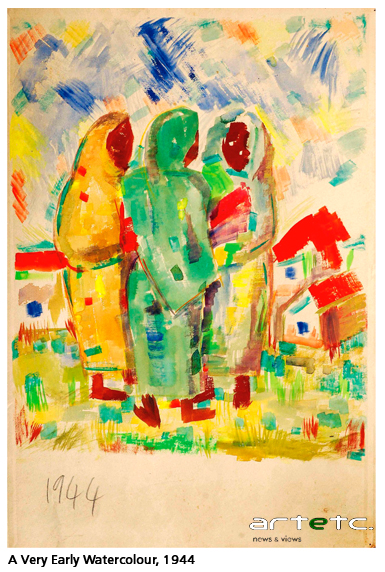

- The Enigma That was Souza

- Progressive Art Group Show: The Moderns

- The Souza Magic

- M.F. Husain: Other Identities

- From All, One; And From One, All

- Tyeb Mehta

- Akbar Padamsee: The Shastra of Art

- Sensuous Preoccupations of V.S. Gaitonde

- Manishi Dey: The Elusive Bohemian

- Krishen Khanna: The Fauvist Progressive

- Ram Kumar: Artistic Intensity of an Ascetic

- The Unspoken Histories and Fragment: Bal Chhabda

- P. A. G. and the Role of the Critics

- Group 1890: An Antidote for the Progressives?

- The Subversive Modernist: K.K.Hebbar

- Challenging Conventional Perceptions of African Art

- 40 Striking Indian Sculptures at Peabody Essex Museum

- Tibetan Narrative Paintings at Rubin Museum

- Two New Galleries for the Art of Asia opens at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

- Raphael, Botticelli and Titian at the National Gallery of Australia

- The Economics of Patronization

- And Then There Was Zhang and Qi

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Random Strokes

- Yinka Shonibare: Lavishly Clothing the Somber History

- A Majestic “Africa”: El Anatsui's Wall Hangings

- The Idea of Art, Participation and Change in Pistoletto’s Work

- On Wings of Sculpted Fantasies

- The Odysseus Journey into Time in the Form of Art

- On Confirming the Aesthetic of Spectacle: Vidya Kamat at the Guild Mumbai

- Dhiraj Choudhury: Artist in Platinum Mode

- Emerging from the Womb of Consciousness

- Gary Hume - The Indifferent Owl at the White Cube, London

- Daum Nancy: A Brief History

- Experimenting with New Spatial Concepts – The Serpentine Gallery Pavilion Project

- A Rare Joie De Vivre!

- Art Events Kolkata-December 2011– January 2012

- Art Bengaluru

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Delhi Dias

- Musings from Chennai

- Preview, February, 2012- March, 2012

- In the News-January 2012

ART news & views

The Enigma That was Souza

Issue No: 25 Month: 2 Year: 2012

Vinod Bhardwaj in Conversation with FN Souza Sometime in 1985

Creative Impulse

Vinod Bhardwaj: What is your opinion about contemporary Indian art?

F. N. Souza: Right now nothing much is happening in the West. In Paris, with the demise of Chagall, even the last remaining living link with modern art has ceased to exist. I believe the artists active on the Indian scene are capable of bringing about a total walk-out by the West. The Western media has its own compulsions. The media there is suffering from feelings of intense rivalry and a sense of being ignored.

V B: Filmmakers such as Satyajit Ray do become the focus of discussion in the Western media. They also manage to elicit enough respect. Why can’t painters get the same status?

F N S: Satyajit Ray poses no threat to Hollywood whereas people like me can prove to be dangerous to the Western art world. At one time my work was exhibited alongside that of leading artists including Picasso and I got very good reviews.

V B: Quite often there is talk of Picasso’s strong influence on your work. How conscious have you been about this influence?

F N S: We cannot help it if Picasso is the grandfather of us all. After all Picasso was born before me. Moreover Picasso himself tended to borrow from non-European art forms, especially the African art. He imbibed all manner of ideas from a diversity of sources. Today, the modern art is dead in Europe. As a matter of fact the highpoint of modern art can now only be seen in India. For a long time the art critics and the artists in India have remained stuck to a narrow vision. The contemporary Indian art has heavy emphasis on a ‘Hindu interpretation’. Communal elements have been at work to create a sort of rivalry among art schools between the western and the Indian styles. This has had no relationship with the aesthetics of art. By its very nature art is all-encompassing and catholic. Indeed in my work I have tended to narrow down the so-called differences between the Indian and the Western styles. God know how many sources have I pressed into service for my art. Recently, at the East-West Encounter forum in Bombay, when Jeram Patel was showing the transparencies of his old pictures, my influence became clearly evident in his work of 1959. At the same forum, Manjit Bawa walked up to me one day to say: “I don’t want to flatter you but the truth is that had you not been here, this sparring between the East and the West would have turned out to be quite insipid.” I believe art is pure entertainment. Its purpose is to excite.

F N S: We cannot help it if Picasso is the grandfather of us all. After all Picasso was born before me. Moreover Picasso himself tended to borrow from non-European art forms, especially the African art. He imbibed all manner of ideas from a diversity of sources. Today, the modern art is dead in Europe. As a matter of fact the highpoint of modern art can now only be seen in India. For a long time the art critics and the artists in India have remained stuck to a narrow vision. The contemporary Indian art has heavy emphasis on a ‘Hindu interpretation’. Communal elements have been at work to create a sort of rivalry among art schools between the western and the Indian styles. This has had no relationship with the aesthetics of art. By its very nature art is all-encompassing and catholic. Indeed in my work I have tended to narrow down the so-called differences between the Indian and the Western styles. God know how many sources have I pressed into service for my art. Recently, at the East-West Encounter forum in Bombay, when Jeram Patel was showing the transparencies of his old pictures, my influence became clearly evident in his work of 1959. At the same forum, Manjit Bawa walked up to me one day to say: “I don’t want to flatter you but the truth is that had you not been here, this sparring between the East and the West would have turned out to be quite insipid.” I believe art is pure entertainment. Its purpose is to excite.

V B: But there is a vast area of art which doesn’t merely excite us or entertain us. Recently I was reading an extract by the famous painter Renoir which said that a painting ought to be comforting and beautiful since there’s no dearth of bad objects in the world. But won’t you like to draw a work on a massive tragedy such as Bhopal?

V B: But there is a vast area of art which doesn’t merely excite us or entertain us. Recently I was reading an extract by the famous painter Renoir which said that a painting ought to be comforting and beautiful since there’s no dearth of bad objects in the world. But won’t you like to draw a work on a massive tragedy such as Bhopal?

F N S: There is no point in getting sentimental about such accidents. This factory mishap has created the need to think at other levels in society. The Americans are now scared as to how safe their own factories are. The Bhopal happening is a technical accident and humanity learns from mistakes.

V B: Paintings such as Guernica have today become a special symbol for the world at large. . .

F N S: Guernica is phoney art. What is there in that painting except for a bullfight? Did Franco or the Nazis give up their atrocities following its creation? This painting was made before the Second World War but it couldn’t mitigate the violence across the world.

V B: Why do you lend so much importance to signatures in your paintings? Is it related to your ego?

F N S: There are many reasons. In the past the artist would be an unknown entity. Today’s society has turned man into an important being. In today’s culture driven by the mass media the artist has to leave his mark on his work. That apart, my signature also becomes an essential part of my painting.

V B: How many paintings do you manage to make in a year?

F N S: There was a time when I would draw two hundred to three hundred. When I showed the transparencies of my one year’s work at the Bombay forum, Bhupen Khakhar told me that after seeing the work he felt he was wasting his time.

V B: Working just a little or working a lot also depends on an artist’s nature. Every artist has his characteristic temperament.

F N S: But why must I take lethargy as a speciality? I am an active artist. Why must I become slow and lazy like Bhupen Khakhar?

V B: You have been quite enthusiastic about the acrylic medium and you even call it the medium of the future.

F N S: In London of the early 1960s, when there was a tendency to popularise the acrylic colours, I was among the few early artists to use the medium. One of Bombay’s young artists Nimisha Sharma has tended to use acrylic in her paintings in an innovative fashion. Her work is non-figurative and on seeing it one realises the potential of acrylic.

V B: You are capable of writing quite well on the subject of art. Why don’t you write a long and serious piece on Indian art for the Western press?

F N S: For that to happen someone has to ask me to write. Writing without being asked to do so would mean the piece would find its way into the wastepaper basket.

V B: Despite your seminal contribution to the development of Indian art, the art institutions in India have ignored you.

F N S: The Lalit Kala Akademi has remained biased towards me. In Bhopal, publicly Swaminathan claims: “O! Souza, we like you a lot.” But my work won’t be acquired by the museum there. Here, the art institutions have remained dominated by the Bengalis and they tend to only promote their own colleagues.

V B: Lately the Baroda school has acquired considerable importance. And these days the narrative art is much under discussion.

F N S: Both in the London Festival catalogue and in her book, Geeta Kapur has placed me at number one. But ultimately she has words of praise only for Bhupen Khakhar, Nalini Malani or Vivan Sundaram. In her list only artists of a certain quality find favour. Those people do not accept me. I can have a full-dress discussion on the issue that Bhupen or Ghulam Sheikh are no artists. They are illustrators.

V B: These days in the West – Especially England – Bhupen Khakhar is a hot topic.

F N S: One major reason behind this is homosexuality. These people also tend to accept their homosexual status. Whatever has happened in Baroda has also been deeply influenced by pop art. I am not prepared to accept kitsch as art. Indeed fine art can never be a popular form. Art itself is incapable of attracting everyone. Popular and kitsch will always exist away from academic art.

V B: But Bhupen Khakhar has given even kitsch a poetic dimension in his art. For instance in one of his paintings even a man eating ‘jalebi’ touches us at many levels.

F N S: Bhupen Khakhar’s art suffers from many faults. His ability to draw is dismal.

V B: In your personal life you have always displayed a special interest in women. You are almost notorious for your interest in women and sex. Does this have an important bearing on your art?

F N S: People tend to display a more than ordinary interest in my personal life. I am staying here at a guesthouse and people are phoning the management to find out which woman is staying with Souza. Who are my visitors and who do I meet. Why can’t people remain busy with themselves?

V B: I have heard that the diary found after the death of German poet Rilke carried the addresses of more than a thousand women.

F N S: Fine. But I’d like to know how many women did Rilke impregnate.

V B: You manage to find your way through Hindi.

F N S: No. I only understand the bazaar Hindi. Just enough to find my way through G. B. Road [Old Delhi’s red-light area].

V B: While well-known British art critics such as John Berger, Lucy Smith and others did write many stray pieces in praise of you, they never mentioned you in their books.

F N S: In the West publishing is a major industry. Those people are quite narrow-minded and do not readily accept a non-European.

V B: Won’t you ever like to return to India to work?

F N S: Towards the end of the 1960s, before I moved to America, I contemplated returning to India. But I think Redmond’s science took me to America. Now it’s been 20 years since I’ve lived in America. We are like straws in the wind. Maybe it was fated to be like this.

V B: Perhaps you believe in your destiny?

F N S: I don’t think in terms of such old-fashioned vocabulary. I only know the language of science. We are all run through a computer program.

The conversation had taken place in 1985.