- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- The Enigma That was Souza

- Progressive Art Group Show: The Moderns

- The Souza Magic

- M.F. Husain: Other Identities

- From All, One; And From One, All

- Tyeb Mehta

- Akbar Padamsee: The Shastra of Art

- Sensuous Preoccupations of V.S. Gaitonde

- Manishi Dey: The Elusive Bohemian

- Krishen Khanna: The Fauvist Progressive

- Ram Kumar: Artistic Intensity of an Ascetic

- The Unspoken Histories and Fragment: Bal Chhabda

- P. A. G. and the Role of the Critics

- Group 1890: An Antidote for the Progressives?

- The Subversive Modernist: K.K.Hebbar

- Challenging Conventional Perceptions of African Art

- 40 Striking Indian Sculptures at Peabody Essex Museum

- Tibetan Narrative Paintings at Rubin Museum

- Two New Galleries for the Art of Asia opens at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

- Raphael, Botticelli and Titian at the National Gallery of Australia

- The Economics of Patronization

- And Then There Was Zhang and Qi

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Random Strokes

- Yinka Shonibare: Lavishly Clothing the Somber History

- A Majestic “Africa”: El Anatsui's Wall Hangings

- The Idea of Art, Participation and Change in Pistoletto’s Work

- On Wings of Sculpted Fantasies

- The Odysseus Journey into Time in the Form of Art

- On Confirming the Aesthetic of Spectacle: Vidya Kamat at the Guild Mumbai

- Dhiraj Choudhury: Artist in Platinum Mode

- Emerging from the Womb of Consciousness

- Gary Hume - The Indifferent Owl at the White Cube, London

- Daum Nancy: A Brief History

- Experimenting with New Spatial Concepts – The Serpentine Gallery Pavilion Project

- A Rare Joie De Vivre!

- Art Events Kolkata-December 2011– January 2012

- Art Bengaluru

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Delhi Dias

- Musings from Chennai

- Preview, February, 2012- March, 2012

- In the News-January 2012

ART news & views

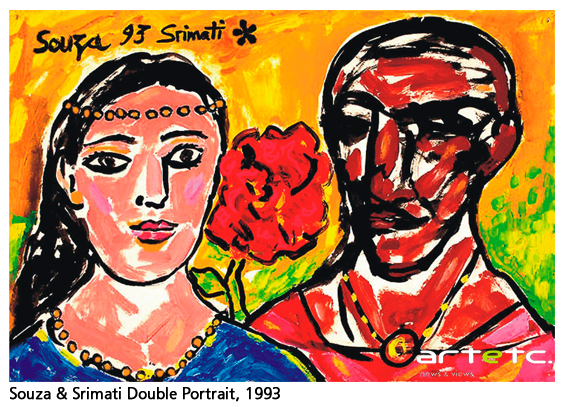

The Souza Magic

Issue No: 25 Month: 2 Year: 2012

Feature

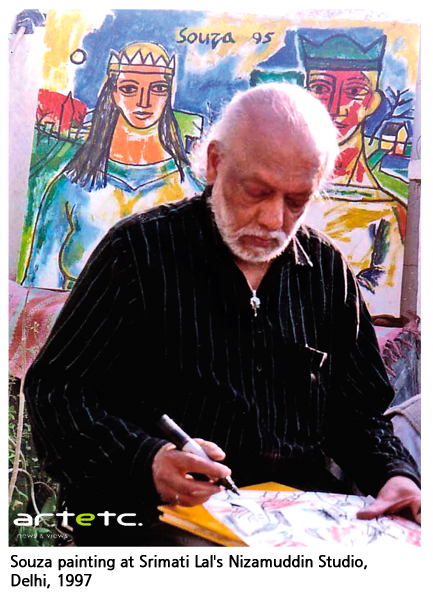

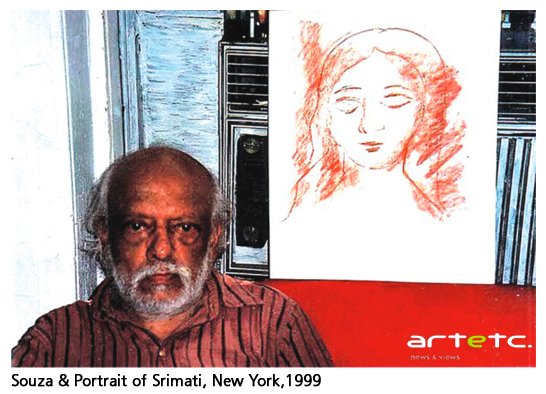

by Srimati Lal

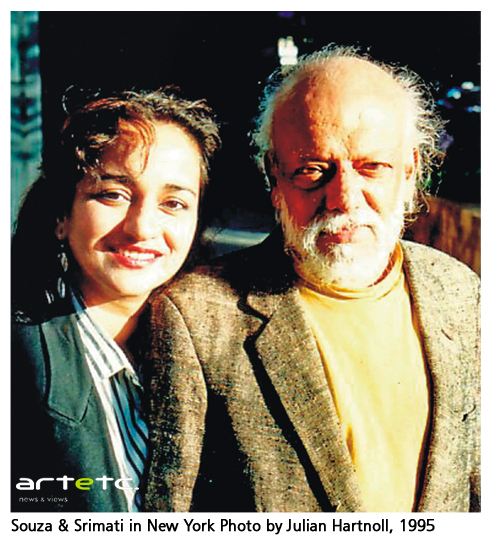

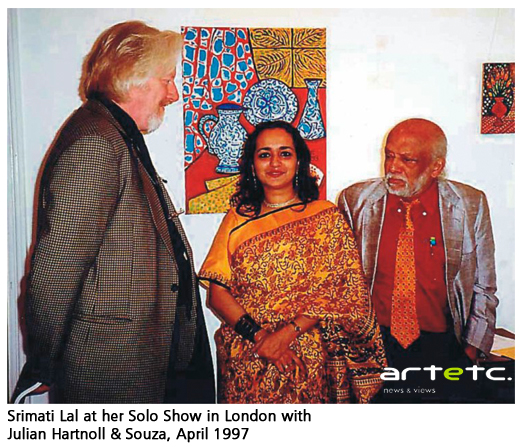

To be both Muse and Curator to one of the world's greatest painters is a unique phenomenon in art history. I have been lucky. Picasso's muse Francoise Gilot and I share striking similarities. We both came from highly-placed families and earned degrees in English Literature, but pursued our own artistic careers as painters against conventional expectations and are internationally-recognised for our work. Francoise and I were both 'discovered' by the two greatest artists of our times – Picasso and Souza – who exalted us as exceptional beauties, bestowing upon us the honour of becoming their Muse.

Francoise and I have lived what is the stuff of dreams for girls. Picasso and Souza painted hundreds of portraits of Francoise and Srimati. Souza transported me as his Muse internationally from Paris to London and New York. .

Francoise and I have lived what is the stuff of dreams for girls. Picasso and Souza painted hundreds of portraits of Francoise and Srimati. Souza transported me as his Muse internationally from Paris to London and New York. .

The age-difference in both equations was over four decades. Picasso's Paris encounter with Francoise happened in 1940; I met Souza over 5 decades later, in 1993 in Delhi.

However, although Souza proposed to me just as Picasso proposed to Francoise, I did not marry Souza, retaining my professional status as his Curator and Aide during the decade that I was Souza's Muse. Picasso did not appoint Francoise Gilot his Curator during his lifetime, tormenting her instead with his egotistic tantrums and autocratic ways until she left him in desperation. By contrast, Souza respected me immensely, often commenting, "Srimati is much more educated than I am!" – with good humour and full earnestness.

I had the privilege of curating over a dozen Souza exhibitions with annotated Catalogs internationally from 1993 to 2002 – exhibitions received with great acclaim, elevating Souza's position as the leader of India's Contemporary Art Movement. Selecting my hometown Calcutta as the venue, I curated Souza's final solo show at Gallerie 88 in April 2001 – one of Kolkata's most important exhibitions. From a Curatorial standpoint I shall explain Souza's position as a pioneer of international contemporary art – and also describe his special equation with me, a remarkable friendship which is a cutting-edge template of the traditional Guru-Shishya Parampara. We were both articulate, outgoing, with similar literary and aesthetic tastes. Souza said he had never discussed as many subjects with a single person as he did with me – and Souza had met the likes of Picasso, Ezra Pound and Stephen Spender! – Souza confessed to me, however, that he found most western intellectuals "dry and pompous." Describing his meeting with Picasso at a European party, Souza confided in me – "I found Picasso terribly dull company. He had a blank stare, and seemed rather dense. In fact, Picasso couldn't even read English: let alone speak it well!"

No wonder Souza and I got along so famously.

Criteria of a Contemporary Art Language

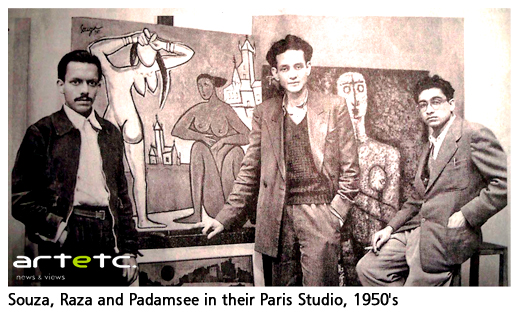

For an entire decade in New York, I witnessed the artistic innovations and prophetic ideations of Souza – a genius ahead of his time. Souza appointed me his Curator from 1993 to 2002. He is the leader and founder of India's urban Contemporary Art Movement, apart from being the first Indian artist to make a mark internationally on his own terms as early as the 1950's.

For an entire decade in New York, I witnessed the artistic innovations and prophetic ideations of Souza – a genius ahead of his time. Souza appointed me his Curator from 1993 to 2002. He is the leader and founder of India's urban Contemporary Art Movement, apart from being the first Indian artist to make a mark internationally on his own terms as early as the 1950's.

Before embarking on an analysis of Souza's oeuvre, certain critical criteria that define contemporary Indian art need stating. These criteria have been evolved by me after considerable research on the movement. It is my conviction that the language of Indian contemporary art is identifiable by the following criteria:

It is Iconoclastic and Secular; It is Urban, as distinct from pastoral; and it is International while clearly retaining its Indian idiom.

No half-measures may be applied to the above essential Modernist facets. However, visual iconoclasm and secularism do not preclude interpretive utilisation of religious iconography – just as an urban artistic language does not necessarily preclude pastoral references.

Souza is a practical paradigm in explaining such subtle nuances of 20th-C. Indian contemporaneity. Souza founded the PAG or Progressive Artists' Group in Bombay in 1947 – unified by an urban artistic style which influenced other groups including the Calcutta Group, Delhi Shilpi Chakra, and Baroda. The initial origins of Indian art-contemporaneity had begun in the 1920's with the then-radical depictions of Sher-Gil and the Expressionist experiments of Rabindranath – but an urban modern Indian art language only evolved after Souza spearheaded the PAG as a Movement in 1947.

Souza is a practical paradigm in explaining such subtle nuances of 20th-C. Indian contemporaneity. Souza founded the PAG or Progressive Artists' Group in Bombay in 1947 – unified by an urban artistic style which influenced other groups including the Calcutta Group, Delhi Shilpi Chakra, and Baroda. The initial origins of Indian art-contemporaneity had begun in the 1920's with the then-radical depictions of Sher-Gil and the Expressionist experiments of Rabindranath – but an urban modern Indian art language only evolved after Souza spearheaded the PAG as a Movement in 1947.

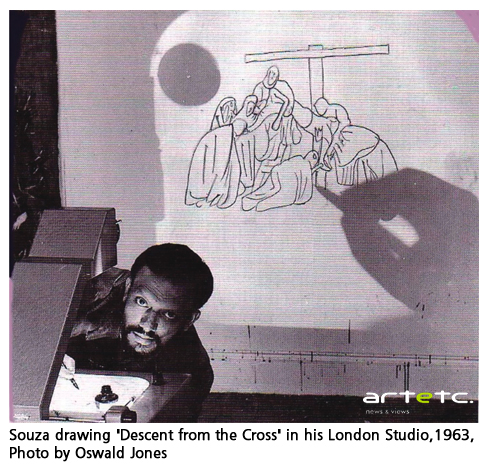

Souza's career spanned six highly-prolific decades from 1944 to 2002, over three continents, celebrating the importance of painterly draughtsmanship, emotion and artistic skill. The ability to draw the human prototype skilfully was as important to Souza's language as it was to Da Vinci, Michaelangelo, Picasso, Sher-Gil and Jamini Roy. Souza deliberately avoided all superficial trends towards theatrical 'installation' and gimmick-ridden 'conceptual art', maintaining that "anyone who calls himself an 'Artist' but who actually cannot draw or paint well, is not an Artist."

Souza as the Original Iconoclast of Modernism

One of the most striking aspects of Souza's iconoclasm was the manner in which he repeatedly and dramatically coalesced the religious with the erotic: two major strands of his oeuvre. As a contemporary art language must embody secularism, it must be clarified that Souza's figurations are, in his words, "forms to hang his paint on."

One of the most striking aspects of Souza's iconoclasm was the manner in which he repeatedly and dramatically coalesced the religious with the erotic: two major strands of his oeuvre. As a contemporary art language must embody secularism, it must be clarified that Souza's figurations are, in his words, "forms to hang his paint on."

Souza's aesthetic and painterly standards come first – if a painting does not stand as a work of art, its content is irrelevant.

We may thus infer that Souza's Crucifixions and Flaggelations of Christ, his female nudes, his radical Chemical transformations, as well as his poetic Goan landscapes, are all, equally, "forms to hang his paint on". In other words, Souza was a deeply secular artist. The concept of Buddhist Nirvana appealed as much to Souza as did the Crucifixion and our own amazingly-contemporary multi-headed, multi-armed Hindu iconography. Souza's autobiography was titled "Nirvana of a Maggot". Despite being Catholic and inspired by the spiritual beauty of Goan churches and rituals, Souza never subscribed to any single religion or 'ism'. He joined the Communist Party briefly in his twenties and rejected it within months "due to disillusionment with its rigidities and hypocrisies".

Souza was nothing if not an iconoclast, as expressed in his violent distortions of even the 'sacrosanct' Christ image. Souza also depicts Christ as dark-skinned – "not artificially flaxen-white, blonde and operatic." In Souza's 1950's Crucifixion bought by the Tate Gallery in 1993, Christ is depicted suspended, without a cross, with jagged edges, clearly intended to depict man's brutality, rather than any kind of 'religiosity'. Souza's 'religious' imagery is thus a radical 'transcreation' of religion, exposing the disturbing innards of Truth, rather than 'religion'.

Similarly, Souza's blatant and disturbing depictions of lovers and the naked form intend to confront the hypocrisy of society and formalised religion's white-washing of spontaneous feelings. Souza deliberately combines the religious and the erotic, to create a 'blasphemous' visual duality – which he referred to as 'sin and sensuality'.

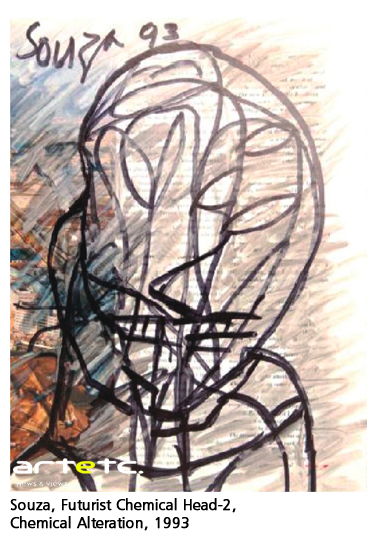

Souza as the Inventor of Two New Art-Forms

In positing the Goa-born Souza as the founder of India's contemporary art, we must be aware that Souza invented two entirely new 'forms' in the contemporary art lexion: the 'Chemical Painting' and the 'Futurist Head'.

An artist-inventor who could thus stretch the language to advanced, cutting-edge realms within 4 decades should rightly acquire the highest value soon after his passing. Souza's artistic inventiveness takes him beyond national confines, making him an International-Treasure Artist, while retaining the Indian-ness that he carried proudly with his Goan ancestry and his identity as an independent Indian.

Souza's 'Chemical Paintings' and 'Futurist Heads' are as significant in art-historical terms as such seminal movements as Impressionism, Expressionism, Cubism and Op Art. Souza's two unique inventions majorly stretch the modern-art lexicon: yet are far less publicised than the work of his counterparts in the west. But the world is now beginning to understand that Souza's genius was ahead of our times. Evidence of this was 'The Souza Room' at the Tate Britain Museum in 2006. In an unprecedented honour for an Indian artist, London's Tate Museum devoted an entire room to Souza for a year – placed next to a room displaying the Surrealists. I was witness to this sanctification of the Souza oeuvre in London and pleased by Souza's strategic placement next to the radical Salvador Dali.

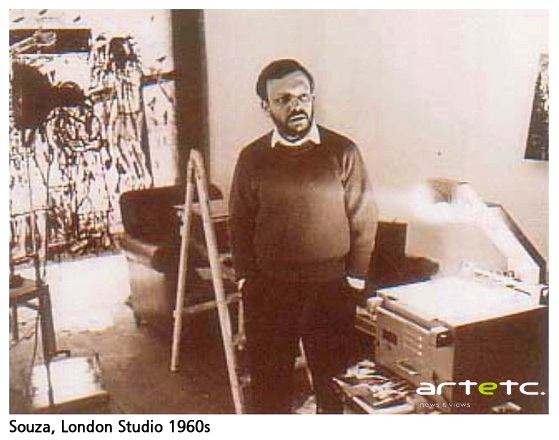

Souza consciously did not work within 'art-coteries', preferring the peace of exile. He evolved his brilliant, radical innovations quietly, in relative obscurity in New York, for four decades from the 1960's to 2002. The full significance of Souza's art of his New York Period is yet to be understood: I shall make a beginning here.

Souza's New York Oeuvre

In New York in the 1960's, Souza was grappling with an urge to 'create a new form of painting'. His wish was granted in 1968, when in a discussion with a Columbia University Chemist, Souza stumbled upon a chemical solvent that could dilute already-existing printer's-inks on glossy magazine-images. Souza began to 're-make' media-images in mainstream American magazines such as Vogue, Life and Hustler, painting on top of these transcended pages, creating multi-dimensional new paintings of a kind never seen.

Before Warhol employed photographs in Pop Art, Souza had explored this terrain and evolved it into the Chemical Painting – a far superior achievement in art-language.

As Souza's closest friend in his last decade from 1993 to 2002, I witnessed the profusion of his Chemical Paintings. He created them fervently: often a dozen or more a day. Souza's Upper-West-Side Manhattan floors were always strewn casually with startling, kaleidoscopic and unique Chemical artworks. I referred to them as Souza's "Fleurs du Mal", after Baudelaire's 1857 "Flowers of Evil". Entrapping and recreating all the angst of modern urban life with shadows of decay, grime, masochism, protest and ennui, these dark Chemicals were not pretty pictures, but 'disturbing, profound art' that embodied a remarkably relevant new art-language accurately reflecting our times.

Souza's Chemicals, in their minutiae and multi-layered intensity, contain more power, truth and tragedy than Warhol's over-exposed 'Pop' blow-ups. I decided in 1993 to analyse and exhibit this new artistic creation by Souza which had remained one of New York's hidden secrets for three decades. In November 1995, I curated the first-ever exhibition of Chemical Paintings Of Souza at Delhi's L.T.G. Art Gallery: an immediate sell-out drawing unending crowds, confirming the visual power of Souza's new form.

Souza's second painterly innovation are his Futurist Heads: a radical development in the history of artistic figuration. Souza's skilful evolution of the human face takes-off here into a new post-modern 'Head' transcending Time, Nation and Gender.

Souza's second painterly innovation are his Futurist Heads: a radical development in the history of artistic figuration. Souza's skilful evolution of the human face takes-off here into a new post-modern 'Head' transcending Time, Nation and Gender.

One of Souza's first visual inspirations was a pre-Christian sculpture conveying tremendous modernism: The Harappa Man, with eyes high up on its forehead and geometrically-stylised features. Observing this 'Harappan' over decades of intensive experimentation, Souza evolved an entirely new 'Head' with characteristic Souza multiple-eyes and variegated 'manic distortions,' accurately-depicting the anguish of the contemporary human.

In Souza's Futurist Head, neither gender nor ethnic origin are identifiable. This remarkable post-Millennial head has morphed into a new and terrifying form. The depiction ends at the neck and shoulders; bodily physiognomy is no longer important. In the culmination of his life, Souza examines the perplexed, frantic human mindscape, choosing to concentrate on the Head alone, thus revealing the tormented inner psyche, rather than 'literal' physiognomy.

Souza's Futurist Head spans a reach from Demi-god to Gladiator, Ulysses to Astronaut. Semi-human, largely supra-human, it is an accurate scientific evolution beyond our current biological language. We know not which mysterious realms these awe-invoking Futurist Warriors have experienced and survived: realms beyond our imagination. The fact that Souza's Futurist Heads are often created with Chemicals is relevant to the gasoline-driven, frenetic millennium that we are all surviving.

Souza The Man: "Nature is the Sole Principle"

Edwin Mullins described Souza's artistic genius thus: "Souza's art straddles many traditions, but serves none." Another critic, Neville Wallis, observed: "Souza is a brilliant satirist of modern man and a draughtsman of concentrated power."

I would prefer to let Souza speak for himself – for Souza is as brilliant a writer as he is a painter.

In his last decade, Souza began writing-down his ideations voluminously in journals that he called "The Paragraph", a final 'Book of Insights'. He wrote while I was seated before him in New York:

"Destiny is nothing but the Law of Nature, and my religion is Nature. Art and Creation is none other than the Force of Nature. Nature, PRAKRITI, is the Sole Principle: the Creator of everything. I use energy from the same universal source that humans used to write the Vedas and the Scriptures."– F N Souza,'The Paragraph'

'Nature is the Sole Principle' is the telling line I selected from my Guru's writings on March, 28, 2002 as Souza's epitaph. It is symbolically carved on his gravestone in Mumbai's Sewrie Cemetery.

Courage and Communication on Canvas

My best friend for ten years, Souza continues to inspire me with the courage of his communications on canvas. The forty-year age difference dissolved when sharing our ideas, philosophies, experiences, witticisms. Perhaps Youth and Age are Mayic illusions; all the frantic calendar-chronologies imposed upon tightly-modulated lives are limitations, in the larger scheme.

My best friend for ten years, Souza continues to inspire me with the courage of his communications on canvas. The forty-year age difference dissolved when sharing our ideas, philosophies, experiences, witticisms. Perhaps Youth and Age are Mayic illusions; all the frantic calendar-chronologies imposed upon tightly-modulated lives are limitations, in the larger scheme.

Communication of the Truth and Courage are what ultimately matter... and too few people seem to have such abilities.

On 19th January 1993 I first had darshan of Souza when he opened an exhibition in Connaught Place, Delhi. I wanted a rare interview with the legend for the Times of India, but had been forewarned that Souza usually refused interviews, complaining that "all journalists ask dumb questions."

Evidently, I did not.

All meetings are Karmic. As a young art critic writing a weekly art column from my Nizamuddin studio, I had a clippings-file of favourite articles; on top was an article by Souza in The Statesman: "Search For An Infinite Universe". I am compelled to believe that this article acted like a talisman bringing me face-to-face with my artistic Guru.

Souza and I were separated by four decades. At 69, life had made him subtler. He no longer looked like the Angry Young Man of Indian artistic legend, that jet-setting artist of the Swinging Sixties, the gadfly leading a London-and-New York high-life whose exhibitions were visited by Yoko Ono and Dirk Bogarde, whose blazing canvasses hung in the world's finest galleries.

In January 1993, Souza was an other-wordly figure with eyes on another plane. I am told that I looked like a college student. Despite such differences, we were also on the same page.

The great artist came and sat beside me, and the dialogue Souza initiated with me that January evening did not pause for a single moment for the ten years that followed. When he left this planet on Maundy Thursday, the day before Good Friday in March 2002, I was curating Souza's final Mumbai show. I sat beside Souza in the ambulance to the ICU, assuring him that guardian-angels were present.

In January 1993, Souza gave me his own paints and brushes to paint-with after discovering my hidden paintings in Nizamuddin. He noticed that we had uncannily-similar drawing and writing-styles. We set incredibly-high standards for our craft, and were difficult to please. I now refer to my dramatic decade as Souza's Muse as my “accelerated Karma in fast-forward", and congratulate myself for retaining my own identity and culling the best of what this experience had to offer.

Souza, my Guru, said he found me wiser than most people his age. At a glittering London party thrown for Souza in 1997, a well-known British art-collector came up to Souza and asked: "Is this lovely young girl beside you your daughter?" – Souza smiled impishly and replied: "No, Srimati is my Mother!"

Souza's hundreds of delicate portraits of Srimati done in New York, Paris, London and India are testament to his affection. Souza's spirit was 'younger' than most of my jaded contemporaries. He followed his dreams more ardently. I later realised that Souza's vision and energy stemmed from his genuine experience of tragedy and struggle. He was self-made; he didn't suffer fools. Souza had seen poverty, death, loss and grief from his earliest years in Saligaon, where he was born on 12 April 1924. His father died at 24, before Souza's birth; Souza's elder sister Zamira died of childhood disease. His widowed, penniless mother Lily Maria Antunis raised Souza singlehanded, paying for his art-education at Bombay's JJ School of Art.

Souza's hundreds of delicate portraits of Srimati done in New York, Paris, London and India are testament to his affection. Souza's spirit was 'younger' than most of my jaded contemporaries. He followed his dreams more ardently. I later realised that Souza's vision and energy stemmed from his genuine experience of tragedy and struggle. He was self-made; he didn't suffer fools. Souza had seen poverty, death, loss and grief from his earliest years in Saligaon, where he was born on 12 April 1924. His father died at 24, before Souza's birth; Souza's elder sister Zamira died of childhood disease. His widowed, penniless mother Lily Maria Antunis raised Souza singlehanded, paying for his art-education at Bombay's JJ School of Art.

Souza had seen enough, and early enough, to be able to see through people: their poses, their pretences. I believe that Souza's humble beginnings made him spiritually brave. He often told me: "Srimati, I don't really belong to this planet!" For ten years, Souza carried me on a magic carpet of visionary ideas: far above the mundane.

In the Gita, Krishna gives Arjun a Vishwarup-Darshan: Arjun suddenly sees the never-ending cycle of birth, illusion, greed, pain, inspiration, duty, diligence, compassion, love and death – all churning together in a cosmic dance.

Souza's paintings convey a part of his vision to the world... but Souza conveyed this darshan directly to me.