- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- What's Behind This Orange Facade!

- “First you are drawn in by something akin to beauty and then you feel the despair, the cruelty.”

- Art as an Effective Tool against Socio-Political Injustice

- Outlining the Language of Dissent

- Modern Protest Art

- Painting as Social Protest by Indian artists of 1960-s

- Awakening, Resistance and Inversion: Art for Change

- Dadaism

- Peredvizhniki

- A Protected Secret of Contemporary World Art: Japanese Protest Art of 1950s to Early 1970s

- Protest Art from the MENA Countries

- Writing as Transgression: Two Decades of Graffiti in New York Subways

- Goya: An Act of Faith

- Transgressions and Revelations: Frida Kahlo

- The Art of Resistance: The Works of Jane Alexander

- Larissa Sansour: Born to protest?!

- ‘Banksy’: Stencilised Protests

- Journey to the Heart of Islam

- Seven Indian Painters At the Peabody Essex Museum

- Art Chennai 2012 - A Curtain Raiser

- Art Dubai Launches Sixth Edition

- "Torture is Not Art, Nor is Culture" AnimaNaturalis

- The ŠKODA Prize for Indian Contemporary Art 2011

- A(f)Fair of Art: Hope and Despair

- Cross Cultural Encounters

- Style Redefined-The Mercedes-Benz Museum

- Soviet Posters: From the October Revolution to the Second World War

- Masterworks: Jewels of the Collection at the Rubin Museum of Art

- The Mysterious Antonio Stellatelli and His Collections

- Random Strokes

- A ‘Rare’fied Sense of Being Top-Heavy

- The Red-Tape Noose Around India's Art Market

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata, January – February 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Art Bengaluru

- Delhi Dias

- Musings from Chennai

- Preview, February, 2012 – March, 2012

- In the News-February 2012

- Cover

ART news & views

A Protected Secret of Contemporary World Art: Japanese Protest Art of 1950s to Early 1970s

Issue No: 26 Month: 3 Year: 2012

by Nuzhat Kazmi

It may come as a great surprise to many in the world that there has been a period of unrelenting political protests by artists through their creative projects in Japan, post World War II. But, perhaps, it may not, come as an absolute surprise, as I write, that this vital historical detail, never did became part of art historical writings otherwise remarkably prolific, emerging post World War II. More importantly that was being published in Japan itself. Significantly, a good part of this art historical scholarship was generated by art scholars in academic institutions, privately funded universities, museums and galleries of international repute. The land of the rising sun has yet to see the sunset of American military bases on its soil. How this American presence has been maintained since Japan lost the war in 1949 is, of course, never focused either by the Japanese Government or the U.S.A and its administration.

But, the fact is, that there was indeed a strong movement of resistance to the American Military’s presence in their country by the Japanese population. There were widespread protests and all strata of Japanese society took to the streets to register their deep mistrust and disgust to the increasing presence of the American military bases. Most major and radical were the protests that were chronicled by Japanese artists. A large section of eminent Japanese artists came out publicly to proclaim their suspicion and revolt, to what they saw was an act of compromise on the part of the Japanese Government, of the dignity and sovereignty of its own people. This resulted in an intensely debated discourse in Japan, which continues, indeed, to this day.

However, the ensuing public display and private discourse, never again acquired the same rebellious nationalist content and revolutionary clarity, as it, indeed, did in the eventful history of the late 1950s, the 1960s, as well as the early 1970s, in Japan. And by 1980s when there was almost a miraculous economic growth and an incredible appearance of a strong Japanese middle class, even the memories of a Japanese protest, a historical phenomenon, was erased. It, the political protest and radical agitation was on the threshold of attaining the stature of a national revolution. Now, it appeared, to have been erased from the collective memory of the Japanese people and the world community, almost altogether.

And, indeed, we owe it to Linda Hoaglund, an American Japanese, who grew in Japan while her parents were there and were occupied in missionary work. Her knowledge of both English and Japanese, her innate facility in the two languages, placed her advantageously. It gave her an understanding of two different points of views, coming from two different political identities and national associations. She has worked for long years in her capacity as an expert translator of the two languages. Her film, ANPO: Art X War, released in 2010, brought to notice the artists and their creative revolutionary actions. She has, with this film, put to the forefront, in the public domain, the Japanese protest art. An extraordinary body of art, extremely avant-garde and radical, applying modern aesthetical values and concepts of universal fundamental rights, registered its strong rebuff to American military and thereby to any political presence in Japan. Japanese pre-eminent artists joined vociferously the collective Japanese attempt to actually dismantle and remove the American bases in Japan. The Japanese intellectuals, artists, students and general masses, were, all gearing together, to oust the reviled American forces from Japan. But, as stated by Linda, the revolutionary national fervour seen till the 1970s soon became almost invisible. By 1980s, there is little that remains of it. From now onwards, is, of course, the miraculous flourishing of the Japanese economy, culture and the profile as a modern nation of Japan and its gaining economic growth, that dominate the public discourse. There has been since, continued celebrations, both local and global, of its contemporary accomplishments and modernity. But nowhere, in all this, was there, ever a reference to a body of, undoubtedly, a politically, historically relevant artistic protest and voicing of revolutionary political stand in Japan. A nation of defeated people, trying to put together its proud identity again, confidently, unequivocally reclaiming for Japan its political integrity, never really ever emerged a movement again. Till as recently as 2010 when Linda Hoagland’s film has, once again thrown open unanswered questions of history and political occupation and by inference of a just political integrity as people’s fundamental right in today’s world.

My attempts here would be to focus on a group of visual artists who took on themselves the responsibility to protest, through their artistic skills and technical means. How they did, and how effective it was to consolidate the objectives of Japanese people, that perhaps, I believe, may still hold power to revolutionize their political ambitions and national consolidation.

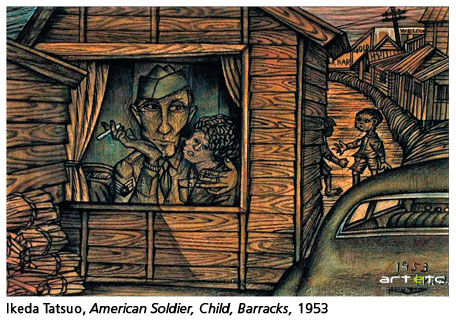

The most extraordinary works are the paintings done around early fifties. Tatsuo Ikeda, American Soldier, Child, Barracks, 1953, is one such artwork. The visual representation is concise and grim in its language. The face of a soldier holding a native woman and looking out from the window of his dim barrack, more young children are seen nearby. Hiroshi Nakamura, was one artist whose large painting done in 1956-7, The Base, speaks the violent foreign presence, brutal occupation of defenseless Japan, post World War II. The work is powerful in its scale and image, severe and unsentimental, confronting the unfair, humiliating treaty signed by the Japan as a fall out of its defeat and American military triumph. The painting speaks of the subjugation of proud people and the daily routine of facing it as their national reality. The visual language used by Nakamura is sharp and violent in its lines. It articulates the aggression, the national humiliation which the dejected, defeated yet self respecting nation is subjected to.

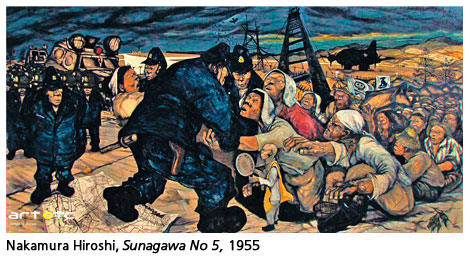

Nakamura’s other artwork, Sunagawa No. 5 like The Base, is speaking of common mass of people confronting the military and Japanese policing. The images are stark and expressive, cutting and violent and the pain of the people, young and old, men and women is visibly stark. However, the dignity of the forbearance marks this group of humanity demanding for its existence with poignancy. Sunagawa No. 5, created in 1955, shows local farmers, struggling against the Japanese police and the expansion of American military facilities in west of Tokyo. In the foreground of the pictorial space, a skull wearing helmet is looking through the machine gun. In the distance, an American tank is visible, engaged in training exercises and there is a body posed like an ostrich, buttocks thrust into the air. This painting actually depicts the “Girard Incident” of January 1957, in which a Japanese woman was shot and killed by one William S. Girard. She was collecting empty cartridges to obviously sell as scrap metal from a field used as an Army shooting range. After much opposition from the U.S., Girard was tried in Japanese court. However, he received a suspended three-year sentence. This theme of meaningless death at the hands of careless American brutes, and the powerlessness of the Japanese to exercise full justice in their own country, was the reference in this powerful Japanese protest painting. Hiroshi Nakamura, was foremost in the Japanese art protest. He established the Japan Youth Artists Association in collaboration with Yutaka Bito, Hiroshi Katsuragawa and Tatsuo Ikeda in 1953. Nakamura's work of this period was influenced by the American military occupation of the Japanese town of Sagawa, and the conflicts between the townspeople and soldiers. His paintings including The Base (1957), was representational in Japan of the Reportage Painting, wherein young artists expressed Socialist concerns through their art. It developed into an idiom that included the European Social Realism and Surrealism. 1973, he was a stage designer for a dance production by Tatsumi Hijikata. From 1974, his artwork has been shown internationally in exhibitions including: Contemporary Japanese Art: Tradition and Present,(Kuntsmuseum, Dusseldorf, 1974; The International Surrealism Exhibition, Gallery Black Swan, Chicago, 1976; Reconstructions: Avant-Garde Art in Japan 1945-1965,The Museum of Modern Art, Oxford, 1985; and Japon des Avant-Gardes: 1910-1970, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, 1986. Nakamura's art has also continued to be exhibited throughout Japan: Reportage Art in Japan, The Itabashi Art Museum, Tokyo, 1988; Japanese Anti-Art: Now and Then, (The National Museum of Osaka, 1991; Art of Modern Japan, The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, 1993; and Art in Nerima ’97--Tatsuo Ikeda and Hiroshi Nakamura, The Nerima Art Museum, Tokyo, 1997.

Nakamura’s other artwork, Sunagawa No. 5 like The Base, is speaking of common mass of people confronting the military and Japanese policing. The images are stark and expressive, cutting and violent and the pain of the people, young and old, men and women is visibly stark. However, the dignity of the forbearance marks this group of humanity demanding for its existence with poignancy. Sunagawa No. 5, created in 1955, shows local farmers, struggling against the Japanese police and the expansion of American military facilities in west of Tokyo. In the foreground of the pictorial space, a skull wearing helmet is looking through the machine gun. In the distance, an American tank is visible, engaged in training exercises and there is a body posed like an ostrich, buttocks thrust into the air. This painting actually depicts the “Girard Incident” of January 1957, in which a Japanese woman was shot and killed by one William S. Girard. She was collecting empty cartridges to obviously sell as scrap metal from a field used as an Army shooting range. After much opposition from the U.S., Girard was tried in Japanese court. However, he received a suspended three-year sentence. This theme of meaningless death at the hands of careless American brutes, and the powerlessness of the Japanese to exercise full justice in their own country, was the reference in this powerful Japanese protest painting. Hiroshi Nakamura, was foremost in the Japanese art protest. He established the Japan Youth Artists Association in collaboration with Yutaka Bito, Hiroshi Katsuragawa and Tatsuo Ikeda in 1953. Nakamura's work of this period was influenced by the American military occupation of the Japanese town of Sagawa, and the conflicts between the townspeople and soldiers. His paintings including The Base (1957), was representational in Japan of the Reportage Painting, wherein young artists expressed Socialist concerns through their art. It developed into an idiom that included the European Social Realism and Surrealism. 1973, he was a stage designer for a dance production by Tatsumi Hijikata. From 1974, his artwork has been shown internationally in exhibitions including: Contemporary Japanese Art: Tradition and Present,(Kuntsmuseum, Dusseldorf, 1974; The International Surrealism Exhibition, Gallery Black Swan, Chicago, 1976; Reconstructions: Avant-Garde Art in Japan 1945-1965,The Museum of Modern Art, Oxford, 1985; and Japon des Avant-Gardes: 1910-1970, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, 1986. Nakamura's art has also continued to be exhibited throughout Japan: Reportage Art in Japan, The Itabashi Art Museum, Tokyo, 1988; Japanese Anti-Art: Now and Then, (The National Museum of Osaka, 1991; Art of Modern Japan, The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, 1993; and Art in Nerima ’97--Tatsuo Ikeda and Hiroshi Nakamura, The Nerima Art Museum, Tokyo, 1997.

Ishii Shigeo, Decoy, 1961, is another commanding work. Here strong use of colours becomes the language of symbolism, expressionism and also of allegorical references to the intangible mirage that resides in the warm seduction of colours. A great deal, over here, is left unsaid, much in the tradition of conventional Japanese art, which has traditionally been, inclined towards reticence and understatement. A trait that is observable in all creative production and more especially in their art of painting and the wood prints of the eighteenth, nineteenth centuries that is, just preceding the twentieth century.

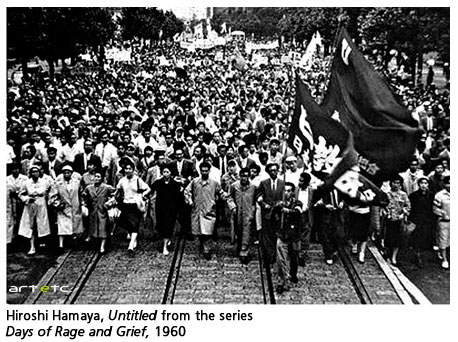

The series Days of Rage and Grief, 1960, photographs by Hamaya Hiroshi, 1960, would indeed remind us of recent political agitations at Tahrir Square in Cairo. Whereas, the protests in Egypt resulted in massive and concrete changes in power structure, in favour of the people, unfortunately that never, actually became a reality in Japan. Here in his photo book, Hamaya applies an anomaly in the oeuvre of an artist known greatly for his romantic images of rural folk and customs, in his need to speak for the grave inhuman injustice meted out to the Japanese people. Hamaya’s art records the emergence of the common citizen into the public political arena, marching defiantly, side by side in anti-Government and anti America demonstrations with labour unions, antiwar organizations and left-wing student groups.

The series Days of Rage and Grief, 1960, photographs by Hamaya Hiroshi, 1960, would indeed remind us of recent political agitations at Tahrir Square in Cairo. Whereas, the protests in Egypt resulted in massive and concrete changes in power structure, in favour of the people, unfortunately that never, actually became a reality in Japan. Here in his photo book, Hamaya applies an anomaly in the oeuvre of an artist known greatly for his romantic images of rural folk and customs, in his need to speak for the grave inhuman injustice meted out to the Japanese people. Hamaya’s art records the emergence of the common citizen into the public political arena, marching defiantly, side by side in anti-Government and anti America demonstrations with labour unions, antiwar organizations and left-wing student groups.

It is not just accidental that the major protest art in Japan aligned with the most devastating events in its history. In 1951, after the American occupation of Japan, a security treaty, known as ANPO in Japan, was signed. This treaty empowered the U.S. to maintain military bases inside Japan. ANPA was revised in 1960. And this time Japanese reacted strongly with massive protests, collectively and individually. It is indeed documented, if nowhere else, in the Japanese creative field of the fifties till early seventies. This was, more overwhelmingly seen in visual representational art and in the films. These clearly document for us, the revolutionary force and determination of the Japanese to reject the security treaty and restore Japanese sovereignty in all matters of governance. The officially erased and collectively forgotten history of the demonstrations against the Japanese government can be said to remain documented in the art that emerged from the protest movement.

As an indicator of the Cold War strategy, ANPO, is short for Anzen Hosho Joyak for the Japanese name for the security treaty. It allows for the stationing of American troops on Japanese soil in exchange for American protection of Japan from foreign threats, even today. With ANPO US secured a foothold in Asia that helped U.S. to wage the obnoxious Vietnam War. It is an inescapable fact that without the close relationship with the U.S., Japan could not possibly have grown at the growth rate it did after World War II. However, it is important to say here that within the jurisdiction of the Japanese constitution, the treaty is indifferent to Article 9, which renounces war as a means to resolve international disputes, and asserts its commitment to peace as sanctified in the constitution’s preamble and upheld by a large portion of Japanese civil society.

Today ANPO remains, and is indeed the most contentious political issues in Japan. This fact was brought to surface at last by the recent protests against the planned relocation of Futenma Air Station in Okinawa. However, the protests did not demonstrate the anger and revolutionary fervour that we witnessed also very recently that of the Arab Spring or even the Wall Street Occupations. But perhaps, the relatively large turnout of people drawn from different strata of society ignites hope that another radical movement is possible in Japan and that the “protest art of Japan” can remind us actually how.

In 1960, millions of Japanese citizens from all walks of life came together in a ‘democratic uprising’. This nationwide movement left an indelible mark on the creative work of the artists who participated. Interestingly, many of whom eventually rose to international prominence. However, the protest art of 50s, 60s and early 70s remains, even today, hidden in museum vaults, out of public gaze.

The ties between art and activism may have been nurtured out of dire necessity. Any escalating yet inherently nonconformist activity, such as protest, would need to be sheltered from the social pressures, and more so in Japan, a nation that has always valued conformity. Protest against the political hegemony of the ruling elite, Japan, as a cultural social entity, will have to conform to the value of radicalism entrenched in avant-garde visual language and artistic medium, and therein, Japan will, indeed, conform to the world culture of protest art.