- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- What's Behind This Orange Facade!

- “First you are drawn in by something akin to beauty and then you feel the despair, the cruelty.”

- Art as an Effective Tool against Socio-Political Injustice

- Outlining the Language of Dissent

- Modern Protest Art

- Painting as Social Protest by Indian artists of 1960-s

- Awakening, Resistance and Inversion: Art for Change

- Dadaism

- Peredvizhniki

- A Protected Secret of Contemporary World Art: Japanese Protest Art of 1950s to Early 1970s

- Protest Art from the MENA Countries

- Writing as Transgression: Two Decades of Graffiti in New York Subways

- Goya: An Act of Faith

- Transgressions and Revelations: Frida Kahlo

- The Art of Resistance: The Works of Jane Alexander

- Larissa Sansour: Born to protest?!

- ‘Banksy’: Stencilised Protests

- Journey to the Heart of Islam

- Seven Indian Painters At the Peabody Essex Museum

- Art Chennai 2012 - A Curtain Raiser

- Art Dubai Launches Sixth Edition

- "Torture is Not Art, Nor is Culture" AnimaNaturalis

- The ŠKODA Prize for Indian Contemporary Art 2011

- A(f)Fair of Art: Hope and Despair

- Cross Cultural Encounters

- Style Redefined-The Mercedes-Benz Museum

- Soviet Posters: From the October Revolution to the Second World War

- Masterworks: Jewels of the Collection at the Rubin Museum of Art

- The Mysterious Antonio Stellatelli and His Collections

- Random Strokes

- A ‘Rare’fied Sense of Being Top-Heavy

- The Red-Tape Noose Around India's Art Market

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata, January – February 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Art Bengaluru

- Delhi Dias

- Musings from Chennai

- Preview, February, 2012 – March, 2012

- In the News-February 2012

- Cover

ART news & views

Protest Art from the MENA Countries

Issue No: 26 Month: 3 Year: 2012

by Sandhya Bordewekar

My first and only visit to the Middle East was more than 20 years ago. Those were the days when the Indian expatriates, especially in the 'forward-looking' UAE, truly believed that they had the best of both the worlds a westernized modern lifestyle within stone's throw from home. Since I was there for more than a month and the weather was comparatively good, I often went for walks and interacted with as many people as I could. The place was squeaky clean, all steel and glass and glitter, vast shopping malls, sprawling private villas hemmed in by tall boundary walls, 'disciplined' streets, almost completely safe at any time of the day or night. Each morning, I scanned the huge bunch of newspapers that arrived for any 'interesting' news. Predictably, they were squeaky clean too sanitized and perfumed, with thick supplements that gossiped of Hollywood stars and European royalty. It was, in fact, too good to be true.

This could not last forever; no matter the degree of easy numbness you could seduce the populace into with the comfort of material security and giddy development. And it did not. Well into the '90s, the first bubble to burst was that of their nouveau cricket supremacy, riddled by serious allegations of match-rigging that robbed the tournaments of all credibility. On its heels, came the movement of the sub-continent's underworld dons to these supposedly safe havens, and then, one after another, stories of labour exploitation of the most inhuman kind. It became increasingly clear that the expatriate, by submitting his/her passport to the employer (as a legal requirement, no less) was really nothing more than a bonded worker.

At the same time in India, the economy was opening up and with the comparatively easy availability of dollars, foreign travel was no longer restricted to businessmen and students. At the turn of the century, well-to-do Indians, jaded with touring the USA, UK, Europe, Singapore, Dubai and Australia, began to look at designer holidays in countries like Turkey and Egypt (very popular), Syria, Yemen, Israel, Jordan, Palestine, Morocco, Lebanon, Algeria (for the more adventurous) and Iran (for the really adventurous). They came back with wonderful stories of these beautiful lands, friendly people, 'disciplined' streets.

So, they were the ones who were the most upset when reports of trouble in Egypt first erupted on Indian news channels. Their fairy tale lands were being mauled by stone-throwing crowds, being made ugly by 'revolting' graffiti sprayed on the spic-and-span public walls, their 'disciplined safety' jeopardized by 'all these people who had nothing better to do'. Nobody really bothered about Tunisia, a small country in the northernmost region of Africa, where the trouble had really started when Mohamed Bouazizi, an unemployed graduate and a street vendor, set fire to himself in front of government buildings in his hometown of Sidi Bouzid.

Why did the ordinary people in the MENA (Middle East and North Africa) countries suddenly rise up in protest and how did they express their protest? We all know that most of the MENA countries are Islamic in terms of religious following and their political leadership often comes from royalty or 'benevolent' dictatorships. Their religion and politics are usually closely inter-twined. Unlike the UAE (much more liberal, but now severely affected by the continuing recession in the USA and Europe), the MENA countries are not really wealthy though most are oil-rich and for years have seen either continual political instability or ruthless dictators with their families and friends looting the lands. Any hint of public questioning or protest has been completely unacceptable and violently and often publicly put down to discourage future incidents of a similar kind. Historically also, right from Mesopotamian times, this entire region has almost always been on the boil, the lands ravaged by wars and seemingly un-resolvable conflicts. And its hapless citizens have been paying the price.

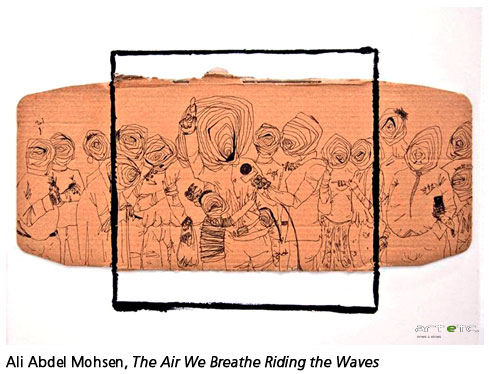

To a large extent, I believe that the Internet has had a significant role to play in the recent wave of political protest that engulfed many of the MENA countries. Communication has always been a powerful tool and the role of regimes, dictatorial as well as democratic, in censoring / modifying / planting news and information to suit their agendas is not unheard of. (The Darb 1718, an art gallery in Cairo, held an exhibition titled Maspero, its title taken from the name of the building that housed Egypt's state-run TV station. The show poked fun at the old mainstream media that was the handmaiden of the powers-that-be. One of the works included was artist Ali Abdel Mohsen's The Air We Breathe/Riding the Waves depicting a crowd of people with turbaned rolls instead of faces, listening to the commanding figure in the centre yelling into the mike.) The Internet opened up channels of information and communication which were extremely difficult to monitor and control. The recurrent waves of economic recession that gripped developed Western countries over the last decade also affected the tourism industry in MENA countries in a major way. But most importantly, the ignominy of Saddam Hussain's downfall and the capture and killing of Osama bin Laden allowed several oppressed people living under dictatorial regimes, for instance, of Hosni Mubarak (Egypt) and Col. Gaddafi (Libya), to think that it is not impossible to find ways in which to revolt, to believe that their exploitative leaders are not as indestructible as the people have been led to believe. One placard read simply “Mubarak: Shift + Del”!

To a large extent, I believe that the Internet has had a significant role to play in the recent wave of political protest that engulfed many of the MENA countries. Communication has always been a powerful tool and the role of regimes, dictatorial as well as democratic, in censoring / modifying / planting news and information to suit their agendas is not unheard of. (The Darb 1718, an art gallery in Cairo, held an exhibition titled Maspero, its title taken from the name of the building that housed Egypt's state-run TV station. The show poked fun at the old mainstream media that was the handmaiden of the powers-that-be. One of the works included was artist Ali Abdel Mohsen's The Air We Breathe/Riding the Waves depicting a crowd of people with turbaned rolls instead of faces, listening to the commanding figure in the centre yelling into the mike.) The Internet opened up channels of information and communication which were extremely difficult to monitor and control. The recurrent waves of economic recession that gripped developed Western countries over the last decade also affected the tourism industry in MENA countries in a major way. But most importantly, the ignominy of Saddam Hussain's downfall and the capture and killing of Osama bin Laden allowed several oppressed people living under dictatorial regimes, for instance, of Hosni Mubarak (Egypt) and Col. Gaddafi (Libya), to think that it is not impossible to find ways in which to revolt, to believe that their exploitative leaders are not as indestructible as the people have been led to believe. One placard read simply “Mubarak: Shift + Del”!

And the people hit back in a medium that was anonymous (and hence individually safe), using public walls as their canvas, painting their anger and frustration in vivid images and colours, sending across defiant messages that rose from deep within their bellies, hearts and minds. It was true Protest Art; art that did not wait to think and consider, deliberate and ponder in the confines of a personal studio space. It only looked for an outlet to send across a message in strong, bold and visual terms; in places that could not be ignored or overlooked. It was Art of the Street, not for genteel salons and elite galleries.

Cairo's Tehrir Square led from the front as a battleground extraordinaire that bore the full brunt of 'people power'. As images of the vast sea of men, women and children delirious from a physical, intellectual and spiritual freedom that they had never experienced before, flashed across TV screens, one began to relate to the graffiti that splashed across walls of street facing residencies and offices, on shop walls and windows, on any plain surface that begged to protest! Tehrir Cinema was a new public event held at night at Tehrir Square where footage of the revolution in progress filmed by filmographers was projected for large crowds.

Students of Cairo's well-known Faculty of Fine Arts College, Helwan University, once banned from creating Protest Art,1 made artworks that told stories of blood, agony and rage, covering their college's drab grey walls in colourful political art. But it also captured the energy, optimism and passion of the youth of Egypt. Youmna Mustafa, a 20-year old girl student, had painted a bound, screaming face. “Not being able to speak your mind, your wants and desires, share your thoughts out loud, is to feel dead,” she said. Anas Muhammad, 21, explored the role that the Internet and Social Media had played in informing the public and publicizing the protests, by painting a 10 x 10 feet panel which featured a man whose head, once helmeted and blinded by state media, is now brilliantly lit by Twitter, Facebook and Al Jazeera! He explained, “Before the Internet, all we had to unify us was the Egyptian flag, which I show bleeding from the disrespect Mubarak showed us."

In a bold step, it was Prof. Sabry Mansour, teacher of Mural Art at the Faculty, who decided to encourage his students to explore Protest Art, banned until then by Mubarak. “We could make better street art than what was happening.” So he got all the 60 students in his class to present a mural design from which the seven best were selected democratically for execution.

One of the selected murals was of Rehan Nabil, an articulate woman student. It was executed on the Ismail Mohammed Street, and depicted a giant, venomous green snake winding through a painting, strangling people and drawing blood. She explained, “This is about Mubarak, the corrupt, the unjust. A true snake who deceived his own people.” She described Mubarak's regime as filled with thieves. “They robbed us of a future.” It was an extraordinarily strong statement, very perceptive, and, in a nutshell, compressed the thinking of every person protesting. The idea of 'freedom' in itself was so overwhelming, that the women students when asked whether they were also protesting for women's rights, answered, “Our country's problems are much bigger than women's rights. This is not about women; this is about everyone. Everything you might want for women -- like opportunity, education, jobs, respect, freedom -- you want for everyone."

The students' murals have become a testament to the anger these young people have felt about the injustices of the past as well as their hope for the future. They are generating smiles and interest from the neighbourhood. "Passers-by are curious," said Prof. Mansour, calling it appropriate and good that the students take public ownership of their pride in helping to change the country. It feels especially good to communicate this by doing something that would have had us arrested not very many weeks ago. Very, very liberating."

Egypt also saw the emergence of a comic book TokTok2 in the post-revolution period. It drew its content from stories emerging in post-Mubarak Egypt. TokTok takes its name from the auto-rickshaw that plies Cairo's crowded streets much like in India. The 'comic' is 'a monthly review that aims to produce a bustling mass of comic strips in a free, contemporary spirit, drawn and edited by its own artists.' The TokTok thus lets 'everyone make their own journey.' Graphic artist Ganzeer made large-sized murals of portraits of those killed during the revolution and put them up in the martyrs' own neighbourhoods in Cairo. These became one of the most visible 'portraits of a movement'.3

Egypt also saw the emergence of a comic book TokTok2 in the post-revolution period. It drew its content from stories emerging in post-Mubarak Egypt. TokTok takes its name from the auto-rickshaw that plies Cairo's crowded streets much like in India. The 'comic' is 'a monthly review that aims to produce a bustling mass of comic strips in a free, contemporary spirit, drawn and edited by its own artists.' The TokTok thus lets 'everyone make their own journey.' Graphic artist Ganzeer made large-sized murals of portraits of those killed during the revolution and put them up in the martyrs' own neighbourhoods in Cairo. These became one of the most visible 'portraits of a movement'.3

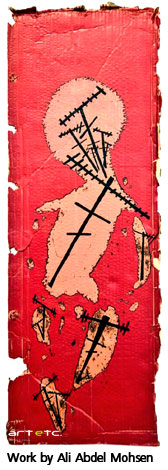

In Sanaa, Yemen, anti-government protestors used their own bodies, specifically their arms and hands, on which they wrote slogans demanding the resignation of President Ali Abdullah Saleh, believed to have killed several peaceful protestors. Young girls with Yemeni flags tied across their mouths showed palms on which was henna-ed in Arabic, “Leave!” If brevity be the soul of wit, in Syria too, posters with a simple cross ('x') drawn across the photo of hated President Bashar al-Assad, sent the message loud and clear. Other 'popular' images of these much-hated men depicted them as burning, flames licking their faces partially, or with a noose predominantly placed around the face, or the face behind bars. In quite a few, one saw protesters slapping the images with shoes and sandals or even actually kicking them.

In Sanaa, Yemen, anti-government protestors used their own bodies, specifically their arms and hands, on which they wrote slogans demanding the resignation of President Ali Abdullah Saleh, believed to have killed several peaceful protestors. Young girls with Yemeni flags tied across their mouths showed palms on which was henna-ed in Arabic, “Leave!” If brevity be the soul of wit, in Syria too, posters with a simple cross ('x') drawn across the photo of hated President Bashar al-Assad, sent the message loud and clear. Other 'popular' images of these much-hated men depicted them as burning, flames licking their faces partially, or with a noose predominantly placed around the face, or the face behind bars. In quite a few, one saw protesters slapping the images with shoes and sandals or even actually kicking them.

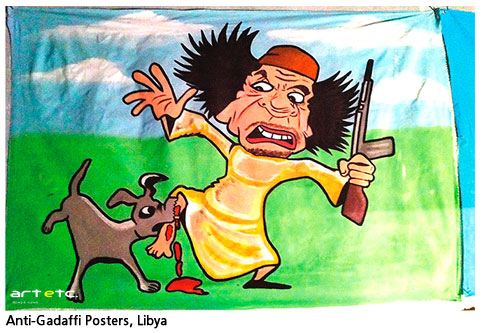

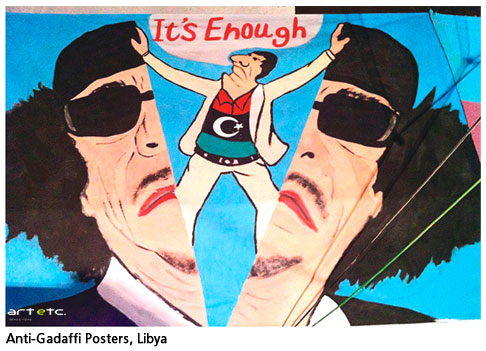

Col. Gaddafi, the self-obsessed Libyan dictator, ruling that country with an iron hand since 1969, got the boot too. There were placards portraying him as a chained pitbull, in the control of a young boy. The most poignant was one held by a child that said, “Please Quit! Let me back to School”. In rebel-held east Libyan towns like Benghazi, Tobruk, Al-Bayda, and Derna, posters openly ridiculing Gaddafi (being bitten by a dog, for instance, and as a monkey picking lice, as a clown), highlighting the blood-thirsty need for power ('I'll either rule you or kill you'), or expressing a repressed society's fury (man splitting a Gaddafi face image into two, another in which he is tied to a rocket to be sent into outer space as a protester with an amputed hand rejoices) are all over the place, in stark and ironic contrast to the thousands of glorifying and official portraits of Gaddafi that were a regular fixture on the Libyan landscape.

The street artists here used his own image as a weapon against him.4 In a visual outpouring of pent-up hatred, these caricatures appeared by the hundreds in the city centres, trashed army bases, public building walls and any other public place that the street artists could lay their brush on. Caricature became the most striking manifestation of their new-found freedom of expression. One must say that Gaddafi's flamboyant and eccentric history did make him a perfect target for satire. Most of the street art in Benghazi was created by a group of young men that called itself Qais al-Halali, after the name of one of their colleagues who was shot by the secret police. When the trouble started they did not reach for their guns but for their coloured pens and spray cans to churn out paper drawings of the detested dictator. “When we started doing this we swore that no one would stop us,” they said.

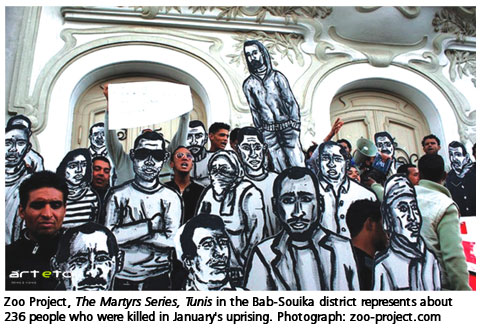

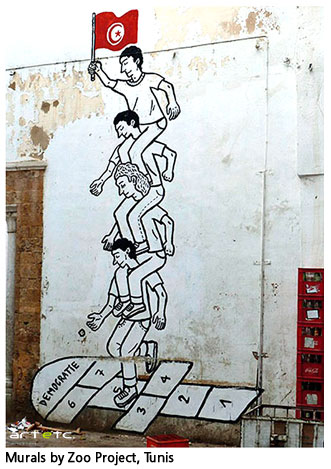

While the struggle for freedom from repressive regimes still continues in these countries, in Tunisia5 at least there appears a closure of some kind, though it is still far from having any kind of democratic system in place. Tunisia gained independence from its French colonial rulers in 1956 but it soon found itself under the autocratic rule of Habib Bourgiba till 1987 and then on under the even more repressive regime of Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali. But in December 2010, the Tunisians rose in revolt and 236 people lost their lives. The Constitutional Democratic Rally party was overthrown on 14 January 2011. The unrest grew out of chronic youth unemployment, social and economic disparities between the affluent coastal regions and the impoverished interior, and a lack of political freedom. Zoo Project, a Franco-Algerian graffiti artist based in Paris, visited Tunis in March-April 2011 and created images of the political struggle underway there. A series of murals were created in addition to 40 life-sized figures representing some of the 236 persons killed in the January unrest. This has been called the Martyr Series and have been publicly installed in the Bab-Souika district, in Tunis and in the Hafisa district amongst other places.

While the struggle for freedom from repressive regimes still continues in these countries, in Tunisia5 at least there appears a closure of some kind, though it is still far from having any kind of democratic system in place. Tunisia gained independence from its French colonial rulers in 1956 but it soon found itself under the autocratic rule of Habib Bourgiba till 1987 and then on under the even more repressive regime of Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali. But in December 2010, the Tunisians rose in revolt and 236 people lost their lives. The Constitutional Democratic Rally party was overthrown on 14 January 2011. The unrest grew out of chronic youth unemployment, social and economic disparities between the affluent coastal regions and the impoverished interior, and a lack of political freedom. Zoo Project, a Franco-Algerian graffiti artist based in Paris, visited Tunis in March-April 2011 and created images of the political struggle underway there. A series of murals were created in addition to 40 life-sized figures representing some of the 236 persons killed in the January unrest. This has been called the Martyr Series and have been publicly installed in the Bab-Souika district, in Tunis and in the Hafisa district amongst other places.

Reference:

1.Colleen Gillard & Georgia Wells for The Atlantic, May 2011, submitted by Marilyn Turkovich on Sat, 09/03/2011 - 14:18,Source:http://www.stumbleupon.com/su/1MDgfl/www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2011/05/the-art-of revolution/238049

2.www.toktokmag.com

3.Documented by Ursula Lindsay

4.Roy Mulholland, The Observer,http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/jun/05/gaddafi-rebels-art-graffiti- benghazi?intcmp=239

5.http://www.guardian.co.uk/globa-development/gallery/2011/may/20/tunisia-murals-zoo-project-in- pictures?intcmp=239#/?picture=374735984&index=8