- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- What's Behind This Orange Facade!

- “First you are drawn in by something akin to beauty and then you feel the despair, the cruelty.”

- Art as an Effective Tool against Socio-Political Injustice

- Outlining the Language of Dissent

- Modern Protest Art

- Painting as Social Protest by Indian artists of 1960-s

- Awakening, Resistance and Inversion: Art for Change

- Dadaism

- Peredvizhniki

- A Protected Secret of Contemporary World Art: Japanese Protest Art of 1950s to Early 1970s

- Protest Art from the MENA Countries

- Writing as Transgression: Two Decades of Graffiti in New York Subways

- Goya: An Act of Faith

- Transgressions and Revelations: Frida Kahlo

- The Art of Resistance: The Works of Jane Alexander

- Larissa Sansour: Born to protest?!

- ‘Banksy’: Stencilised Protests

- Journey to the Heart of Islam

- Seven Indian Painters At the Peabody Essex Museum

- Art Chennai 2012 - A Curtain Raiser

- Art Dubai Launches Sixth Edition

- "Torture is Not Art, Nor is Culture" AnimaNaturalis

- The ŠKODA Prize for Indian Contemporary Art 2011

- A(f)Fair of Art: Hope and Despair

- Cross Cultural Encounters

- Style Redefined-The Mercedes-Benz Museum

- Soviet Posters: From the October Revolution to the Second World War

- Masterworks: Jewels of the Collection at the Rubin Museum of Art

- The Mysterious Antonio Stellatelli and His Collections

- Random Strokes

- A ‘Rare’fied Sense of Being Top-Heavy

- The Red-Tape Noose Around India's Art Market

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata, January – February 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Art Bengaluru

- Delhi Dias

- Musings from Chennai

- Preview, February, 2012 – March, 2012

- In the News-February 2012

- Cover

ART news & views

A ‘Rare’fied Sense of Being Top-Heavy

Issue No: 26 Month: 3 Year: 2012

Market Monitor

by Art Bug

Art market watchers were in for a surprise on February 7, the big evening at the London quarters of Christie’s, when British sculptor Henry Moore’s Reclining Figure: Festival soared to 19.1 million pounds ($30.3 million) compared with pre-sale estimates of 3.5-5.5 million. Christie's said it was an auction record for the artist. The second stunner of the evening came in the surreal section, when Spanish painter Joan Miro’s record was smashed with his Painting-Poem that went for 16.8 million pounds ($26.6 million), double its estimate. And finally it was Vincent Van Gogh's Vue de l'asile et de la Chapelle de Saint-Remy, from the collection of the late Hollywood actress Elizabeth Taylor, which raised 10.1 million pounds ($16 million) versus expectations of 5.0-7.0 million.

The buzz on Twitter and other social-media was, are we back to the good old days of 2008, when any big-ticket auction-floors only meant fire-on-ice?

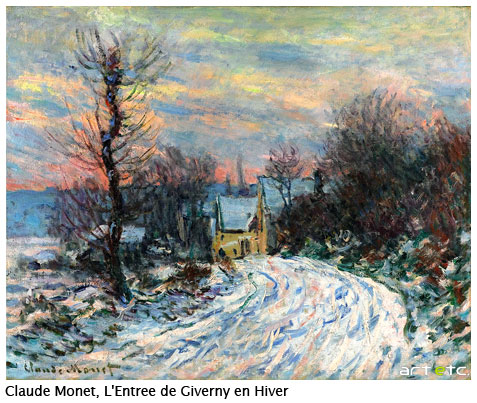

The next day, it was the turn of Christie’s biggest competitor Sotheby’s to come up with their big-evening. A snowscape by Claude Monet, L'Entree de Giverny en Hiver, fetched the night's high price of 8.2 million pounds, above the high estimate. And a painting by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner went under the hammer for 7.3 million pounds, at the top end of expectations. However, the star of Christie’s, Joan Miro stumbled, despite being the top lot at Sotheby’s. Miro, along with Gustav Klimt, went unsold at the floors. Klimt was later bought through a private transaction, but the price was a notch below the lower estimate.

By February 9, people weren’t that sure anymore of the return of the ‘good-old-days’, but were still being influenced by the predictions of the duopoly before the start of the season. The duopoly had predicted a combined revenue of around 500 million pounds from its February sales, which was more than their combined revenue of 425 million dollars around the same time, during the depression-recovering 2011. By the end though, the two competitors were able to manage a heist. Financial Times’ Georgiana Adams reported “The sales of contemporary art at Christie’s and Sotheby’s in London this week continued their gravity-defying up-wards trajectory, both topping their high estimates and handing in high sell-through rates. Christie’s on Tuesday had the stronger catalogue and boasted the star lot of the week: Francis Bacon’s lilac-hued “Portrait of Henrietta Moraes” (1963), with an unpublished estimate of £15m-£20m. It made a chunky £21.3m (estimates don’t include premium; final prices do), the top price in the sale and in the fortnight. A gorgeous green and blue abstract by Gerhard Richter swept to £9.9m (est £5m-£7m) and almost £5m was given for Christopher Wool’s Untitled 1990 work reading Fool, a new price high for the artist. With a total of £80.6m, the sale nudged the top end of its presale target of £84m and was 89 per cent sold by lot. Only one other Christie’s contemporary art auction in London has done better, and that was in June 2008 – before the world’s economic meltdown.

The boom-time feeling washed over into Sotheby’s evening sale on Wednesday, which turned in a punchy £50.7m, more than pre-sale estimations and with all but six of the 63 lots finding buyers. Again the buzz of the evening was Richter. The top lot, a grey and white abstract, fetched £4.9m, topping the £4m made by a more obviously commercial red abstract. The six Richters on offer totalled £17.6m, well above their upper estimate of £14.18m.

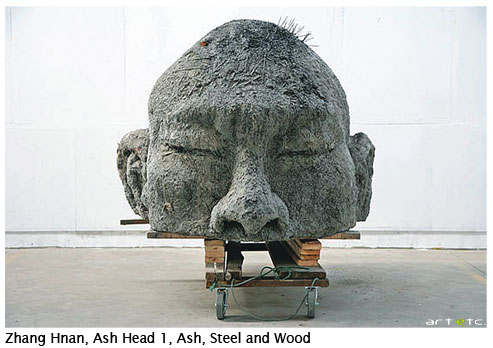

The Chinese artist Zao Wou-Ki, who is immensely popular in China, also scored strongly. A blue and white abstract sailed to £1.8m, well above expectations of just £500,000-£700,000. And someone (presumably Charles Saatchi) was finally able to offload Zhang Huan’s giant sculpture Ash Head 1 (2007), which was shown in the Saatchi Gallery in 2008-09 but then failed to sell in Hong Kong in October 2009. It sold for £228,304, on its upper estimate of £150,000-£200,000.”

The Chinese artist Zao Wou-Ki, who is immensely popular in China, also scored strongly. A blue and white abstract sailed to £1.8m, well above expectations of just £500,000-£700,000. And someone (presumably Charles Saatchi) was finally able to offload Zhang Huan’s giant sculpture Ash Head 1 (2007), which was shown in the Saatchi Gallery in 2008-09 but then failed to sell in Hong Kong in October 2009. It sold for £228,304, on its upper estimate of £150,000-£200,000.”

But aren’t these results in contrast with the current overall financial situation in Europe? How does one explain such phenomenal performance in the very continent, where most countries are going through a moderate-to-acute financial crisis?

The managing director of ArtTactic’s analytical group Anders Petterson, commenting on ArtTactic’s ‘Art Market Outlook 2012’ had told Reuters before the start of the season that, “Overall the tone is neutral with a positive bias. If something really major happens in the (financial) markets then all bets are off, but if things stay as they are we are likely to see a continuation of current levels. The auction houses will focus on the very top end and the very rare works of art for which there will be people with the money to buy no matter what's happening on the markets.”

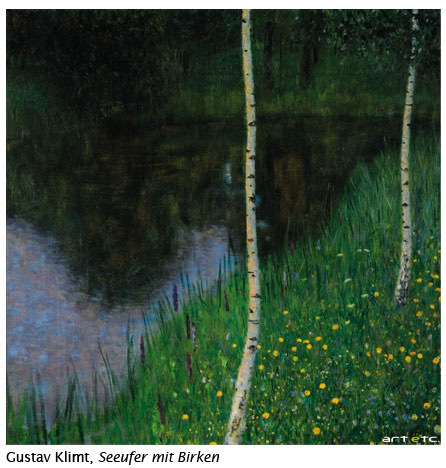

The catch-phrase here is ‘very rare works of art’. And that is exactly what the London auctioneers had focused upon last month. However, one must also take note that one of the top lots at Sotheby’s February 8 sales, Gustav Klimt's recently rediscovered landscape Seeufer mit Birken painted in 1901 which was not seen in public for more than a century, went unsold on the floors. So is rarity the only precondition?

The catch-phrase here is ‘very rare works of art’. And that is exactly what the London auctioneers had focused upon last month. However, one must also take note that one of the top lots at Sotheby’s February 8 sales, Gustav Klimt's recently rediscovered landscape Seeufer mit Birken painted in 1901 which was not seen in public for more than a century, went unsold on the floors. So is rarity the only precondition?

Art market analysts disagree. They are of the opinion that there needs to be a fine balance between rarity, quality, volume and variations. As Sydney Morning Herald’s Sarah Thornton wrote towards the middle of last month, “It is worth noting that Sotheby's and Christie's 10 highest-spending families may be responsible for as much as 10 per cent of their revenue. This teeny elite includes the Qataris and, most likely, Russian oligarchs, US hedge-fund managers, Chinese billionaires, and Europeans with relatively ''old money''. These people use Christie's and Sotheby's as an upmarket department store.

Indeed, they don't only acquire paintings from the auction houses but rugs, furniture, lighting, silverware, jewellery, watches, books, wine and beach houses. If these 10 players dropped out of the market, the auction houses' figures wouldn't look so hot.”

This is but a fact. An article published on challenges.fr explains that, “the art market is attracting new investors who have been frightened away from the Stock Market”. The Art Media, in a February 17 report reveals, “Robert Read from Hiscox expressed a similar opinion on the situation, writing in the Financial Times that, “There is a lot of cash around at the moment but not many places to put it”. The art market is benefiting from the current economic and financial instability, but also from the growing number of collectors and millionaires, mostly from Asia, as well as industrialisation of the market, set to become more globalised thanks to the internet. The financial crisis is having an effect, but is only one of a number of factors.”

However, there needs to be a reality-check of the situation too. It is obvious that this growth affects only the dizzying heights of the art market and the privileged few. ArtInfo quoted economic analyst at Reuters, Felix Salmon in this regard. He was of the opinion that these buyers do not consider art as an investment. He said that the only exception were a small minority of people with the financial, technical and intellectual capacity to control the market. For Salmon, “art doesn’t have returns, it just sits there, being expensively insured. It pays no dividends, and it can’t be marked to market, since the only way to find out the market price for an artwork is to sell it.”

But, if the current focus on ‘rarity’ is to be maintained, an artwork once bought sould not ideally circle the market before 10 years at least, the more the better, and that would mean a major investment decision on the part of the buyer, who will be able to block the funds over a considerable number of years. And that is where the outspoken Sarah Thronton makes a point: “the biggest spenders are unlikely to abandon the market because, for them, art is more than an investment. It is a fast track to social acceptability and part of their claim to be the distinguished cream of the crop. For the rest of us, it pays to remember that art is about cultural enlightenment: and that flows from contemplating the work, not owning it.”

However, there is one shimmer of worry in this whole scheme of things. Apparently, all the action is taking place at the ‘blue-chip’ end of the market. But what about the lower ends, and the medium-level buyer? Thornton points out that financial advisers are of the opinion that, “While buying emergent art is high-risk, speculative investment, acquiring established masterpieces is perceived as the opposite - a back-up in hard times. If all goes wrong in the world that rare, portable, 1964 Marilyn by Andy Warhol will still be worth something.”

But then, being top-heavy never really contributed anything to agility. And if EVERYTHING goes wrong, who will buy Warhol’s Marilyn?