- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- What's Behind This Orange Facade!

- “First you are drawn in by something akin to beauty and then you feel the despair, the cruelty.”

- Art as an Effective Tool against Socio-Political Injustice

- Outlining the Language of Dissent

- Modern Protest Art

- Painting as Social Protest by Indian artists of 1960-s

- Awakening, Resistance and Inversion: Art for Change

- Dadaism

- Peredvizhniki

- A Protected Secret of Contemporary World Art: Japanese Protest Art of 1950s to Early 1970s

- Protest Art from the MENA Countries

- Writing as Transgression: Two Decades of Graffiti in New York Subways

- Goya: An Act of Faith

- Transgressions and Revelations: Frida Kahlo

- The Art of Resistance: The Works of Jane Alexander

- Larissa Sansour: Born to protest?!

- ‘Banksy’: Stencilised Protests

- Journey to the Heart of Islam

- Seven Indian Painters At the Peabody Essex Museum

- Art Chennai 2012 - A Curtain Raiser

- Art Dubai Launches Sixth Edition

- "Torture is Not Art, Nor is Culture" AnimaNaturalis

- The ŠKODA Prize for Indian Contemporary Art 2011

- A(f)Fair of Art: Hope and Despair

- Cross Cultural Encounters

- Style Redefined-The Mercedes-Benz Museum

- Soviet Posters: From the October Revolution to the Second World War

- Masterworks: Jewels of the Collection at the Rubin Museum of Art

- The Mysterious Antonio Stellatelli and His Collections

- Random Strokes

- A ‘Rare’fied Sense of Being Top-Heavy

- The Red-Tape Noose Around India's Art Market

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata, January – February 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Art Bengaluru

- Delhi Dias

- Musings from Chennai

- Preview, February, 2012 – March, 2012

- In the News-February 2012

- Cover

ART news & views

Writing as Transgression: Two Decades of Graffiti in New York Subways

Issue No: 26 Month: 3 Year: 2012

by Sunanda K Sanyal

Of all the genres invented in the history of modern art, “protest art” is one of the broadest and most open-ended, not least because it encompasses a wide variety of forms, materials, processes and aesthetics. What is more, if Picasso’s Guernica shares this rubric with anti-apartheid posters from South Africa, then the definitions of the two words --“protest” and “art”-- not only become thoroughly contextual, but it also crucially matters who defines them. In other words, the question of protest can be a confounding one in certain discourses of representation, as in the case of graffiti in New York City.

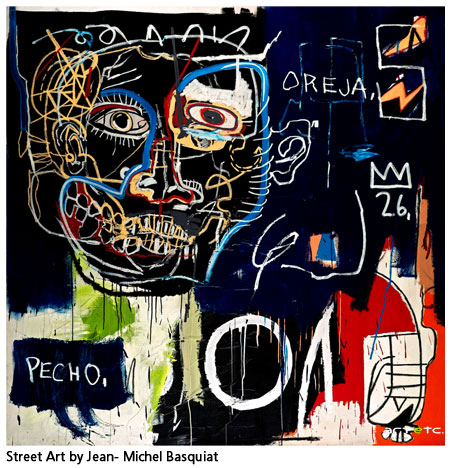

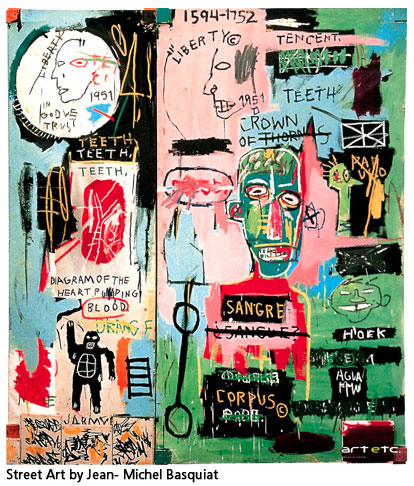

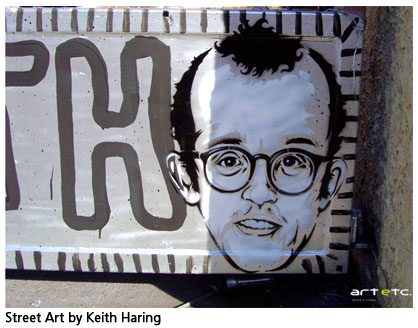

Graffiti is, at the same time, both an antique and a postmodern image-making gesture. Rooted in the Greek word graphein, meaning “to scratch, draw or write”, it is found as far back as in ancient Pompeii; but as a subject demanding attention of art historians and visual culture critics, it acquired new meaning in the post-industrial cityscapes of the late twentieth century. Contrary to common misconception, graffiti is not synonymous with street art—any picture on a public surface isn’t necessarily graffiti. Whereas the use of linguistic signs is not mandatory for street art, it is precisely so for graffiti; in fact, the young graffiti-makers of New York prefer to call it “graffiti writing”, or simply “writing”. Furthermore, while many kinds of street art are authorized and legal, transgression of societal and systemic norms is fundamental to graffiti. Therefore, at best, it can be regarded as a specific kind of street art. Works of New York street artists of the 1980s, such as Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat, cannot be classified as graffiti, even though both of them socialized with local graffiti writers and borrowed from their strategy of dodging the law to draw in public places. Graffiti on the subway trains of New York City in the 1970s and the 1980s was closely tied to the emergence of hip-hop culture, with its break dance and rap music. Its complex legacy left an indelible mark on the city’s social and cultural discourses, before having an international impact. This essay highlights a few facets of its local history.

Graffiti is, at the same time, both an antique and a postmodern image-making gesture. Rooted in the Greek word graphein, meaning “to scratch, draw or write”, it is found as far back as in ancient Pompeii; but as a subject demanding attention of art historians and visual culture critics, it acquired new meaning in the post-industrial cityscapes of the late twentieth century. Contrary to common misconception, graffiti is not synonymous with street art—any picture on a public surface isn’t necessarily graffiti. Whereas the use of linguistic signs is not mandatory for street art, it is precisely so for graffiti; in fact, the young graffiti-makers of New York prefer to call it “graffiti writing”, or simply “writing”. Furthermore, while many kinds of street art are authorized and legal, transgression of societal and systemic norms is fundamental to graffiti. Therefore, at best, it can be regarded as a specific kind of street art. Works of New York street artists of the 1980s, such as Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat, cannot be classified as graffiti, even though both of them socialized with local graffiti writers and borrowed from their strategy of dodging the law to draw in public places. Graffiti on the subway trains of New York City in the 1970s and the 1980s was closely tied to the emergence of hip-hop culture, with its break dance and rap music. Its complex legacy left an indelible mark on the city’s social and cultural discourses, before having an international impact. This essay highlights a few facets of its local history.

New York is unquestionably the most diverse metropolis in the world. The largest city in the United States with a population of over eight million, it is composed of five massive boroughs, three of them islands (Manhattan, Brooklyn and Staten Island) and the remaining two mainland communities (Queens and the Bronx). While the boroughs were consolidated into one city in 1898, each of them makes up a state county (somewhat like the concept of the district in India). The extensive transit system linking four of the boroughs (except Staten Island) is the fourth busiest in the world, carrying over five million riders on a weekday. Partly elevated (visible above ground, the oldest section of which was built in the 1870s) and partly subterranean (opened in 1904), the subways are managed by the Transit Authority, a subsidiary of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority. In the early 1970s, the trains became the target of a prominent subculture of graffiti with roots in the city’s economic and social changes that had occurred through the previous two decades.

The Great Depression of the 1930s and the uncertain period of the World War left New York City in dire need of economic and infrastructural reforms, which were undertaken in the early 1950s. Social equity was not among the priorities of the project. The numerous small manufacturing and goods-based industries located in the central city that had provided jobs for the large number of mostly non-white population were victimized by this massive post-industrial renewal effort. Once old buildings were torn down to make room for new commercial and upper-middle-class residential spaces, the real estate value skyrocketed, resulting in the displacement of the lower classes from commercially prospective locations. At the same time, the overcrowded, disenfranchised neighborhoods full of condemned buildings were denied any infrastructural improvement. By the mid-1960s, powerful corporations had moved into the city, especially to Manhattan; and no longer able to afford the high establishment cost, the small industries supporting the local immigrant population had either closed down or moved to the newly designed suburbs, which represented another facet of the urban renewal scheme.

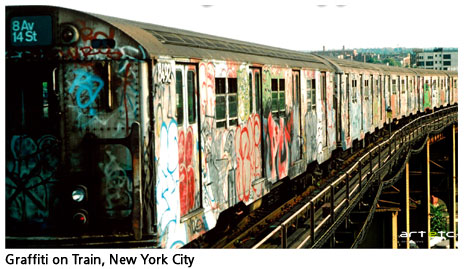

A large portion of the white middle-class left the central city and bought new homes in the planned neighborhoods of suburbia, located at a safe distance from the boroughs. They used the automobile as a primary means of transportation to commute to the city, a privilege that poor New Yorkers could not afford. To make it worse, several of the deprived neighborhoods were further marginalized when the new expressways, built at the expense of mass transportation to accommodate the road traffic, cut through them. Such unequivocally class conscious, discriminatory reform policies implemented over a decade turned New York City into the nucleus of global capital, but one that was punctuated by congested pockets of unemployment, poverty, and crime. Through the 1970s and much of the 1980s, parts of the Bronx, Brooklyn and Queens had no less than a post-apocalyptic look, effectively captured in films like Fort Apache, the Bronx (1981) and Wild Style (1983). Thus, many of the affluent (primarily white) New Yorkers and suburbanites, who had the power to voice their opinions in the media, chose a vision of the city that was compatible with their cultural and class values: not only did they see the dereliction and adversity of large parts of the boroughs as the “urban problem” hindering the progress of an otherwise prosperous metropolis, but they often held the disenfranchised population responsible for their own condition. It is in this scenario that graffiti emerged on the subway trains as a resounding voice of the Other.

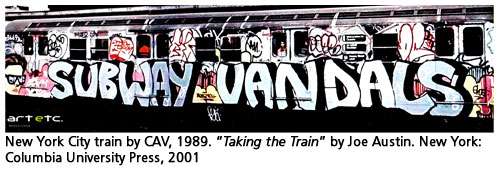

Until the mid-1960s, graffiti in New York had been produced by street gangs on neighborhood walls, primarily to mark their territories. From around 1969, however, it began to appear on the interiors and exteriors of subway trains; and in the early 1970s, there were rapidly growing communities of writers in all four boroughs linked by the transit system. The majority of them were non-white male teenagers from low-income families, with little or no prospect of higher education or jobs. Some of them had various degrees of art training, and almost none were attached to violent gangs. They painted the trains by trespassing the poorly guarded yards spread across the boroughs where the trains were parked overnight. Use of the paintbrush in this enterprise is unheard of; instead, writings were done exclusively with a variety of aerosol spray-cans and magic markers, which, as a custom, were shoplifted, rather than legitimately purchased.

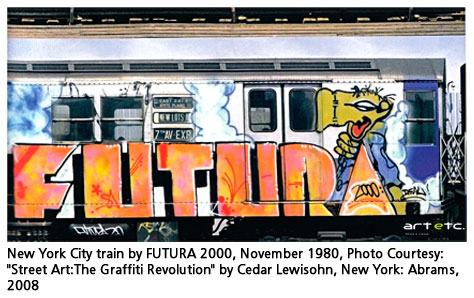

Initially, the images were what the writers called “tags”, or stylized individual signatures. But once they realized that the trains carrying the tags across the city served as a mobile publicity medium, the writing became increasingly complex and colourful, with tags accompanied by figurative motifs and slogans. Numerous groups of writers, called “crews”, were formed after 1973, and an elaborate terminology was born. To tag a surface was to “hit” it; writing on large surfaces was known as “bombing”; “getting up” was making one’s public debut as a writer; a “throw-up” was a tag made rapidly on a single surface, as opposed to a “piece” (short for “masterpiece”), demanding substantial time and effort; a “burner” was an honorific term reserved for a well executed piece; a “toy” was a novice or uncommitted writer. Individual writers most commonly used pet names, often coupled with the street numbers of their home addresses, such as TAKI 183, FUTURA 2000, Phase 2, TRACY 163. There were names without numbers as well, such as LEE (Lee Quiñones, b. 1960), a legendary writer active around the early 1980s; and LADY PINK (Sandra Fabara, b. 1964), a contemporary of LEE and one of a handful of female writers.

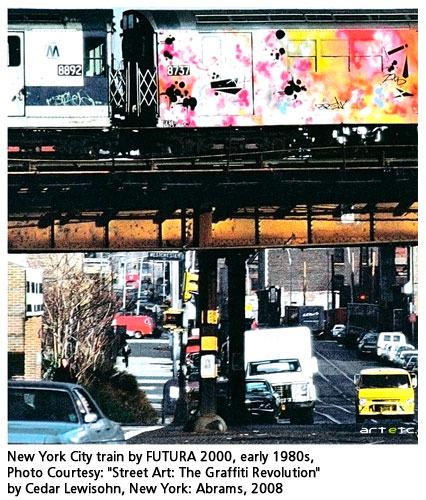

The writings on the exteriors of trains ranged from multiple images on one side of a compartment, to a single piece occupying an entire side. A work that covered both sides of a compartment was called a “whole-car” piece, reserved for the most skilled and innovative writers. Eventually, a complex aesthetic and a prestige system evolved within the writers’ communities. Writers had a spot at Manhattan’s Grand Central station, where they gathered regularly to discuss and critique trains that passed by, and some of the names circulated across the boroughs became legends. Different lettering styles also emerged, such as “bubble” (tags floating amidst painted clouds or bubbles); “blockbuster” (three-dimensional letters relieved by deep shadows); and “mechanical” (heavily distorted, broken letters). Likewise, multiple strategies of treating the train surface developed through the 1970s: a solid background from which the contrasted images jumped out, as opposed to a deep space where the solidity of the surface dissolved under a cornucopia of tags and pictorial motifs. Some of the tags were legible –if not always comprehensible-- to the public, whereas others were so complex that only other writers could read them. In fact, much of the writing was more a dialog between individual writers and crews, rather than with society at large. By the late 1970s, many of the writers were keeping “black-books”, in which they meticulously planned elaborate pieces before executing them on site. The specific train routes that covered the longest distance across the boroughs became the most prized targets.

It was easier to write inside a train while it was running; the writers simply had to wait until the other passengers disembarked. But writing on the exteriors was a nocturnal adventure that lasted hours and demanded dozens of spray-cans and organized teamwork. A strict work ethic was important for the writing activity. Members of a crew were fiercely loyal to the group, albeit with occasional defections. With no profit motive, pride in their own camaraderie and creativity was all they had. Crews worked both on collective productions and on tags of individual members, which made authorship an interesting issue within the group setting. Writing over an existing piece –known as “crossing out”—was generally considered unethical and would lead to fights, unless the previous writer was collectively deemed unworthy due to some unethical acts of his own. In addition, spraying over the numbers and other official information on the train exteriors, and maps and advertisements inside the compartments, was usually avoided.

There is no question that the thrills of the game were as important to the writers as its creative aspect: the thrill of trespassing the yards at night without getting caught; the thrill of avoiding the electrified third rail while in a yard; the thrill of shoplifting spray-cans and markers; and not least, the thrill of watching one’s works on trains run through the boroughs. As Lee Quiñones, playing the role of the writer ZORO in Wild Style, asserts: “Being a graffiti writer is taking the chances and shit, taking the risk…” Absent in the other components of hip-hop culture, this risk-taking of graffiti writing was surely a form of subversion of institutional norms leading to a sense of empowerment, which put the writers at the top of the city authority’s list of enemies. Whether the writing itself was a protest, however, is a tricky question, since the pieces rarely offered any rebellious content. Rather, like hip-hop generally, it was an expressive medium that articulated the untapped creative energies of a youth class completely shortchanged in the previous decades by New York’s ambitious restructuring project. The writers never damaged any trains or stole from the yards; but from the authority’s perspective, spray-painting the trains was an unequivocal act of vandalism; and along with trespassing the yards, it was a punishable offense. The Transit Authority was therefore determined to eradicate graffiti from the trains.

The urban renewal had failed New York’s subway system; by the 1970s, it was ailing with myriad operational and managerial problems. Yet ironically, far from recognizing the writers’ effort to introduce colour and vitality to an otherwise drab and depressing transit scene, the TA, a large of section of the citizenry and the news media saw graffiti writing as a detestable form of assault on civilized life by a tribe of pariahs. Constant negative propaganda in the media soon produced a myth of graffiti as an exacerbating factor in the grim look of the subways; the scene of a spray-painted train running on an elevated line against the background of shabby buildings became a symbol of neglect, lawlessness, and depravity. Thus, instead of focusing on the real problems, including the rising crime rate in the subways, the TA kept the anti-graffiti sentiment alive and consolidated its efforts to defeat the writers. With the backing of the city administration, a vandalism squad was formed in the mid-1970s, which secured the yards, repainted and buffed the affected trains, and arrested writers whenever possible. This official resistance, however, proved completely ineffective when it faced the zeal of the agile and determined teenagers. The cat-and-mouse game continued over the next few years at the cost of millions, but the writing remained unabated. The TA had no choice but to abandon the project around 1979.

By the early 1980s, graffiti writing on New York’s subway trains had become international news. While it was an exotic sight many tourists were anxious to see, the TA and the city administration were equally anxious to avoid showing it, as they were convinced that it projected a deplorable image of New York. The TA thus made a second attempt to combat the writers by forming the Anti-Graffiti Task Force, and this time they won. Both police officers and attack dogs were employed to guard the yards at night; arrests were made more efficiently, by using some writers as informants to tell on others; black-books and other writing supplies were confiscated; spies from the Task Force “crossed out” writings of one crew by forging the name of another, which caused fights between the two groups; negative propaganda in the media was more carefully worded than in the 1970s; a sizeable staff buffed and repainted the spray-painted trains much more quickly and competently than the writers could rewrite on them; and most importantly, new trains were imported with a paint-resistant surface. All of these factors were instrumental in pushing the writers off the subway system by the early 1990s. They moved to other spaces, such as neighbourhood walls, which the Task Force was less inclined to retake. More importantly, with the disappearance of writing on moving trains, the inter-borough communication among the writers gradually collapsed, and the subculture became almost entirely localized within small areas, losing its grander appeal.

It would be wrong to assume, however, that everyone in New York was against graffiti writing. Letters and articles in newspapers frequently opposed the official stand against “cleaning up” the trains, arguing instead that graffiti was actually an improvement on the appearance of the subway, and drawing attention to the futility of the misplaced anti-graffiti investments. A part of the New York art establishment had a leading role in this position, with such celebrated artists as Andy Warhol and Claes Oldenburg speaking in support of the writers. What is more, in the extravagant art market of the early 1980s, some of the graffiti writers were commissioned indoor murals and canvas images by certain New York galleries. Fashionably branded as “post-graffiti”, they were exhibited with fanfare and received with enthusiasm. Fashion Moda, an alternative space in south Bronx, was one of the pioneers in this endeavor. Writers like FUTURA 2000, LEE and LADY PINK had considerable success in gallery circles, selling in an international market and hobnobbing with the who’s who of the New York art world. The limelight produced for them a new kind of authorship that was neither possible nor relevant in the subway context. Yet to many writers, robbed of its radicalism and free spirit, this wasn’t graffiti at all. The remarks of ZORO from Wild Style resonate with this view. “Graffiti ain’t canvases!” says ZORO. “Graffiti’s on the trains, and on the walls. It ain’t got nothin’ to talk about!”

It would be wrong to assume, however, that everyone in New York was against graffiti writing. Letters and articles in newspapers frequently opposed the official stand against “cleaning up” the trains, arguing instead that graffiti was actually an improvement on the appearance of the subway, and drawing attention to the futility of the misplaced anti-graffiti investments. A part of the New York art establishment had a leading role in this position, with such celebrated artists as Andy Warhol and Claes Oldenburg speaking in support of the writers. What is more, in the extravagant art market of the early 1980s, some of the graffiti writers were commissioned indoor murals and canvas images by certain New York galleries. Fashionably branded as “post-graffiti”, they were exhibited with fanfare and received with enthusiasm. Fashion Moda, an alternative space in south Bronx, was one of the pioneers in this endeavor. Writers like FUTURA 2000, LEE and LADY PINK had considerable success in gallery circles, selling in an international market and hobnobbing with the who’s who of the New York art world. The limelight produced for them a new kind of authorship that was neither possible nor relevant in the subway context. Yet to many writers, robbed of its radicalism and free spirit, this wasn’t graffiti at all. The remarks of ZORO from Wild Style resonate with this view. “Graffiti ain’t canvases!” says ZORO. “Graffiti’s on the trains, and on the walls. It ain’t got nothin’ to talk about!”

Such “harnessing” of graffiti writing by the official art milieu turned out to be a double-edged sword. It is abundantly clear that the art world –predominantly white and upper class-- was neither able nor willing to comprehend the fundamental impetus of graffiti writing or its socioeconomic background. Rather, like many other fads of postmodernism, its interest in graffiti was yet another neo-primitivist curiosity; a momentary obsession with an exotic discourse from the margins of society. So as the interest in the gallery images by graffiti writers waned within a few years (as opposed to the sustained markets for both break dance and rap), the fifteen minutes of fame ended for the writers; the demand for their work receded, and most of them were back on the street. Many have considered this a deplorable form of exploitation. But despite this uncomfortable relationship between the two domains, it is also true that the legitimization of graffiti writing by the art world made it an important topic in the discussion of contemporary art and visual culture, spawning an impressive array of research and literature. In short, this contact significantly altered the way contemporary art is perceived.

As I observed earlier, while transgression was certainly integral to the act of graffiti writing in the New York subways, whether the product itself can be seen as protest art is an open question. However one may choose to answer that question, there is no doubt that the history of this counter-culture has the potential to educate us on a variety of issues, from class and ethnic discrimination in a capitalist society, to creative expressions of empowerment under such constraints. Graffiti continues to be produced on walls in New York, but the subway writing represents a uniquely vibrant phase in its history. Yet most intriguingly, none of the images embellishing that history exist any more, except in reproductions; and that, too, only from the 1980s.