- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- What's Behind This Orange Facade!

- “First you are drawn in by something akin to beauty and then you feel the despair, the cruelty.”

- Art as an Effective Tool against Socio-Political Injustice

- Outlining the Language of Dissent

- Modern Protest Art

- Painting as Social Protest by Indian artists of 1960-s

- Awakening, Resistance and Inversion: Art for Change

- Dadaism

- Peredvizhniki

- A Protected Secret of Contemporary World Art: Japanese Protest Art of 1950s to Early 1970s

- Protest Art from the MENA Countries

- Writing as Transgression: Two Decades of Graffiti in New York Subways

- Goya: An Act of Faith

- Transgressions and Revelations: Frida Kahlo

- The Art of Resistance: The Works of Jane Alexander

- Larissa Sansour: Born to protest?!

- ‘Banksy’: Stencilised Protests

- Journey to the Heart of Islam

- Seven Indian Painters At the Peabody Essex Museum

- Art Chennai 2012 - A Curtain Raiser

- Art Dubai Launches Sixth Edition

- "Torture is Not Art, Nor is Culture" AnimaNaturalis

- The ŠKODA Prize for Indian Contemporary Art 2011

- A(f)Fair of Art: Hope and Despair

- Cross Cultural Encounters

- Style Redefined-The Mercedes-Benz Museum

- Soviet Posters: From the October Revolution to the Second World War

- Masterworks: Jewels of the Collection at the Rubin Museum of Art

- The Mysterious Antonio Stellatelli and His Collections

- Random Strokes

- A ‘Rare’fied Sense of Being Top-Heavy

- The Red-Tape Noose Around India's Art Market

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata, January – February 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Art Bengaluru

- Delhi Dias

- Musings from Chennai

- Preview, February, 2012 – March, 2012

- In the News-February 2012

- Cover

ART news & views

Awakening, Resistance and Inversion: Art for Change

Issue No: 26 Month: 3 Year: 2012

by Dr. Seema Bawa

Once upon a time there was a drummer, a 'dholi', who lived in a corrupt king's reign. Every time there was a mishap, misappropriation or crime he would play his drum, and hearing his drum the subjects of the kingdom knew that the king was not performing his duty of dispensing justice and protecting his people. The king, as is their wont, became very angry with the drummer and asked him to stop playing his drums immediately and forever. The drummer, however, refused to be cowed down and stood in front of the palace gates and beat his drums loudly and continuously till the palace guards came and beheaded him in order to silence his drums. Till the last moment he kept singing, “Dhol aur bajega, dhol hamesha bajega, dhol nahin rukega…” that the drums will play forever. This act of brutality against an artist, who acted as the people's conscience, awakened the people who deposed the evil king and replaced him with a just one. The voice of the artist remained in collective memory as a warning and an inspiration.

As a child I had seen the above folk tale performed by puppeteers and such was its impact that I still have vivid memory not only of the performance per se but also my reaction to it. Safdar Hashmi was one such drummer whose voice still speaks even after the dominant ideology tried to silence it. A committed communist and theatre activist who passionately believed in the potential of action in bringing about change, he resigned as a lecturer in a prestigious Delhi University college to work full time with his theatre group Jan Natya Manch or Janam. He would often come to our home to get artwork and posters designed for Janam, or other cultural activities from my artist father, Manmohan Bawa. My father and uncle, Manjit Bawa also closely collaborated with Safdar in organising demonstrations and an art auction for communal harmony after the 1984 riots.

I remember Safdar as a very soft spoken, gentle soul who never raised his voice to make a point, but passionately and with great firmness argued for the causes he believed in. The poster of Safdar painted by my father after his death, showing him in black and white except for a red muffler and a warm smile, encapsulates the joie de vivre, the charisma, the humour and warmth that embodied Safdar. No wonder he left an impact on almost everyone he came in contact with. It is also no wonder that his murder at the hands of political goons as he was performing with his theatre group at the working class neighbourhood at Jhandapur in Sahibabad left the entire artist community shocked and outraged. One remembers that first day of 1989, when almost all artists of all ilk gathered at the hospital praying for his life and the deep sense of personal loss that each of us who knew him felt at his passing away of 2nd of January.

To continue his struggle, and not allow his voice and cause to be muffled artists of all sorts: musicians, theatre professionals, painters and sculptors, architects, dancers, puppeteers, folk and contemporary, gathered together under the aegis of SAHMAT, Safdar Hashmi Memorial Trust, to protest against communalism and to celebrate Safdar. Amongst the many events, such as Anhad Garje, that voiced the anguish of the artist community against the Babri Masjid demolition and subsequent communal violence, a travelling exhibition of artworks created by many artists, including M F Husain, travelled from Delhi to Mumbai to demonstrate solidarity with the cause of communal harmony.

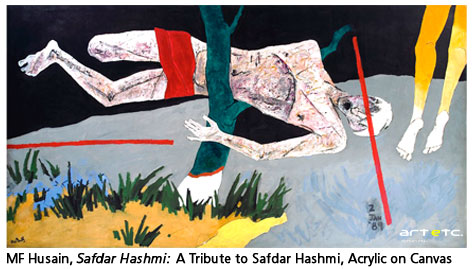

Husain's own painting Safdar Hashmi portrays him as a fallen comrade. Hashmi is shown lying prostrate in the fork of a leafless tree, against a dreary grey and black backdrop. There is sparse grassy surface in the foreground and a trouser-less disembodied leg can be seen leaving the scene. The main figure has his mouth perhaps screaming silently as a red rod pushes against the upper face. Another rod lies near the feet. The awkwardly positioned limbs and the skeletal appearance of the whitish pale figure suggest use of extreme force and torture. The protagonist in the painting is left hanging between the ground and the sky above, between redemption and purgatory, seeking freedom, personal and collective.

Husain has always painted around iconic figures in society from national figures like Mahatma Gandhi and Mother Teresa to popular figures from Bollywood such as Madhuri Dixit. He could and did create an iconographic code around each of these, so that one could recognize not only the figure but also Husain's interpretation of the persona in each painting. But the treatment of the protagonist in his Safdar Hashmi is different, for the figure does not resemble Safdar or iconify him in any way. It is a very personal response to an event and a person who moved him deeply at many levels: emotionally, socially, and politically. The painting per se not only talks about the life and death of an artist but also about energising and awakening people to rise against the oppression, injustice and ongoing struggle against an inequitable society.

The artist's empathy with Safdar is palpable, for Husain too suffered from persecution at the hands of right wing fanatics that made him an exile, living away from his home and homeland. His right to expression and freedom of creativity were questioned, his paintings and indeed his house and galleries vandalized.

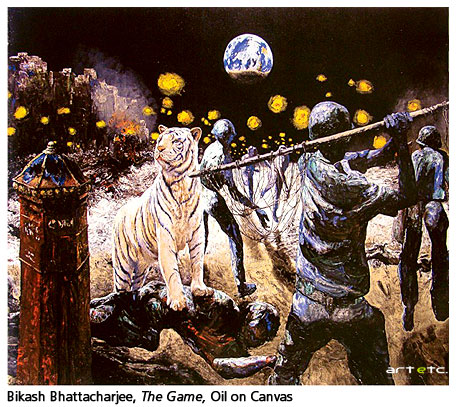

From the individual as a symbol of protest to society up in arms, the ambit of protest in Bikash Bhattacharjee's works widen during the 1970's in which he brings alive the horrors of repression by the state. Known for his soft and romantic figures, set against ethereal backdrops with menacing undertones, the body of work made during Naxal periods comes as surprise. The Naxalibari movement in Bengal and parts of Bihar in the 1970's attracted a number of idealistic young men and women to its cause, who left their homes for villages where they hoped to bring about a revolutionary change with the help of the farmers. Many adopted violent means to achieve this goal, using crude arms against symbols of bourgeois state authority, be it the local thana, or the district magistrate. The Congress ruled West Bengal government unleashed a brutal repressive campaign against these young men and women and thousands were either killed or imprisoned.

Many filmmakers and artists sympathised with the cause of the Naxalites and/or were shocked at the state reprisal against the very young, innocent and naïve youth who had taken up the cause of the peasants in a wave of idealism. They felt that the punitive action was not warranted, especially the brutality with which it was executed. The horrors included student rebels hiding in manholes as automobiles passed them by, interrogation of family members of suspected leaders and participants, reminiscent of the atrocities committed by colonial powers on their subjects or during ethnic cleansing.

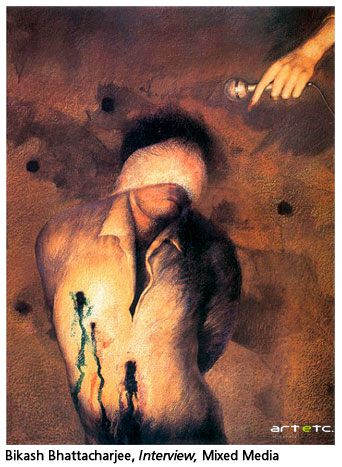

During the heyday of Naxalite fervour in Bengal, Bhattacharjee produced two kinds of paintings, both equally disturbing in the inherent overt and concealed violence contained in them. One was the doll series in which cherubic dolls, children's playthings with rounded limbs and red cheeked faces become actors in the paintings. They hang from a tightrope between buildings or rummage in a chest of drawers, half of the body hanging out or a disembodied face and body stick out of the ground as if these are the only body parts that have pushed up from a grave, the dolls perhaps alluding to young men and women playing dangerous, political games with very serious and indeed fatal consequences.

The other series had more direct references to state terror. A blindfolded youth being interrogated by a mike holding feminine hand is an indictment of the state and the media both. The comprador media, or the insensitive media or indeed the blind media the image is astonishingly percipient and relevant even today. Decapitated heads of the dead and the dying staring at the viewer with a hopeless gaze, that makes the viewer want to get up and help, to cry out or at least give a last sip of water to the dying man on whose face blood has started to cake.

In The Game, an astonishingly fierce and violent composition, a white Bengal tiger stands proudly poised above a bloodied recumbent figure, perhaps its victim. The night sky with its cool earth-moon and yellow balls of fire stand out against a distant cityscape where fires burn, perhaps funeral pyres. In the foreground and the backdrop human figures wearing helmets like the police surround the tiger, one raising a stick and a net to catch and maim the animal. An aura of fear and suspicion, of action and reprisal envelop the canvas.

Moving from the socio-political to the unabashedly political are the paintings by Shuvaprasanna that have anti Communist Party of India (Marxist) imagery. He made these works to register his protest against the perceived misrule of the left parties in West Bengal. In his work Agenda No mmxi -for Right Decision the artist has painted what seems like a moment from a satirical skit of an imagined meeting of the leaders of CPIM. A group of somewhat misshapen men, dressed in white kurtas, many venerably white haired and balding and one sari clad are shown seated behind a table. In fact, it represents the Politburo with caricatured but very recognizable faces of its members who are seated around the red shrouded body, presumably of leftist ideology in form of the grand old man of the party, Jyoti Basu. All of them seem to be arguing but not getting anywhere.

In another work entitled Red Terror three men wearing red caps are stabbing a recumbent green sari clad woman. Painted in 2007 the painting points at the violence unleashed on the protesting villagers of the Nandigram area by cadres of the CPIM. The woman in the painting alludes to the land acquired by the Bengal government for creating an SEZ in order to create space for putting up an automobile manufacturing factory by a leading industrial house. The villagers protested against this acquisition, leading to prolonged resistance and use of counter force, not to speak of the politicization of the issue by all leading parties, especially the Trinamool Congress. Shuvaprasanna's protest against the policies and politics of the left, as a ruling party in West Bengal or at the centre, though mediated by his own political allegiances, is refreshingly direct and bold.

In another work entitled Red Terror three men wearing red caps are stabbing a recumbent green sari clad woman. Painted in 2007 the painting points at the violence unleashed on the protesting villagers of the Nandigram area by cadres of the CPIM. The woman in the painting alludes to the land acquired by the Bengal government for creating an SEZ in order to create space for putting up an automobile manufacturing factory by a leading industrial house. The villagers protested against this acquisition, leading to prolonged resistance and use of counter force, not to speak of the politicization of the issue by all leading parties, especially the Trinamool Congress. Shuvaprasanna's protest against the policies and politics of the left, as a ruling party in West Bengal or at the centre, though mediated by his own political allegiances, is refreshingly direct and bold.

Guernica marks the universalisation of protest. Because of the scale of the event, being part of the Spanish fascist movement and the precursor to the Second World War; and also because of the reputation of the artist, Pablo Picasso on a worldwide stage, Guernica is part of common parlance; even though it is a small town in the Basque Country in Spain, made significant by the painting more than its own geography and history. Such is its impact that when I typed Guernica, the world processing program on my computer did not mark it as an unknown or wrongly spelt word by underlining it with red, as it does with most Indian words including Naxalism.

The black, grey and white painting done in his signature Cubist style is filled with contorted human, mainly women and children and animal forms. The painting seems to emanate from the horse in the centre, whose body overlain as it is with a skull, is being gored by a bull underneath, while a woman mourns the dead child in her arms. Many more dismembered parts make up the composition, such as the dying soldier, a frightened dove, a light bulb, the stigmata and architectural context of a room.

The painting was created in 1937 as a response to the bombing of the town of Guernica by Nazi planes in support of the Nationalist Fascist leader Francisco Franco. Guernica was regarded as the northern bastion of the Republican resistance movement (made up of many ideologies such as Communist, Anarchists and Socialists) and furthermore it was the epicenter of the fiercely independent Basque culture. Not just the site but also the timing was significant, for it was market day and almost the entire town had gathered at the centre. And as the men were away fighting as part of resistance force, the brunt of the bombing was felt by women and children. Their vulnerability and innocence has been shown dramatically in the painting by Picasso who often presented women and children as perfection of mankind, thus any attack on them was an assault on the soul of humankind.

Made at the behest of Republicans, it became a symbol of anti- Franco movement in Spain upto the 1970's and it has been at the centre of Basque nationalism and pride, which uses its imagery to press for their rights. Guernica has had a far wider impact than just Spain, for it has become a worldwide symbol of the atrocities of war, and has been used as an anti- war symbol. From Anti Vietnam war peaceniks to a tapestry of the painting at the United Nations, the imagery has become synonymous with anti- war demands.

Art has always been an instrument of registering resistance to hegemonic ideologies and rule. Be it agit-prop art popularised by Brecht or subversive art of the African American community or inversive art practiced by late twentieth century feminist painters, or original public art based, site specific anti-commercial agenda of the Documenta Projekt, cultural protest has a wide impact on both memory and practice. Protest through art within the context of homogenising culture that tries to gloss over concealed violence and inequalities of class, caste and gender; cultural production is an important medium to express discontent and register resistance. Hope for change lies in the subversion of the dominant and hegemonic ideologies and power structures, often expressed by artists who have the power to be heard and seen, the power of ideological and cultural legitimacy.