- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- What's Behind This Orange Facade!

- “First you are drawn in by something akin to beauty and then you feel the despair, the cruelty.”

- Art as an Effective Tool against Socio-Political Injustice

- Outlining the Language of Dissent

- Modern Protest Art

- Painting as Social Protest by Indian artists of 1960-s

- Awakening, Resistance and Inversion: Art for Change

- Dadaism

- Peredvizhniki

- A Protected Secret of Contemporary World Art: Japanese Protest Art of 1950s to Early 1970s

- Protest Art from the MENA Countries

- Writing as Transgression: Two Decades of Graffiti in New York Subways

- Goya: An Act of Faith

- Transgressions and Revelations: Frida Kahlo

- The Art of Resistance: The Works of Jane Alexander

- Larissa Sansour: Born to protest?!

- ‘Banksy’: Stencilised Protests

- Journey to the Heart of Islam

- Seven Indian Painters At the Peabody Essex Museum

- Art Chennai 2012 - A Curtain Raiser

- Art Dubai Launches Sixth Edition

- "Torture is Not Art, Nor is Culture" AnimaNaturalis

- The ŠKODA Prize for Indian Contemporary Art 2011

- A(f)Fair of Art: Hope and Despair

- Cross Cultural Encounters

- Style Redefined-The Mercedes-Benz Museum

- Soviet Posters: From the October Revolution to the Second World War

- Masterworks: Jewels of the Collection at the Rubin Museum of Art

- The Mysterious Antonio Stellatelli and His Collections

- Random Strokes

- A ‘Rare’fied Sense of Being Top-Heavy

- The Red-Tape Noose Around India's Art Market

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata, January – February 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Art Bengaluru

- Delhi Dias

- Musings from Chennai

- Preview, February, 2012 – March, 2012

- In the News-February 2012

- Cover

ART news & views

Journey to the Heart of Islam

Issue No: 26 Month: 3 Year: 2012

Review

by Shelina Begum

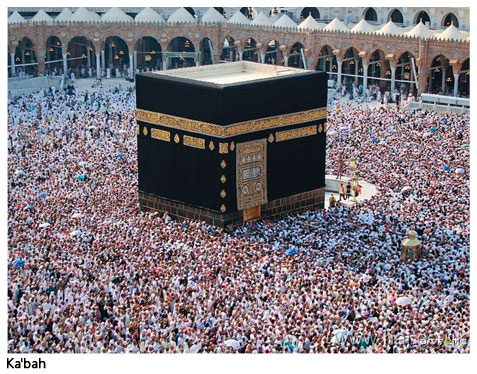

Hajj: Journey to the Heart of Islam is an exhibition at the British Museum in London that tells the phenomenon story of Hajj, unique among the world religions, from its beginnings until the present day. Though it was sub-named Journey to the Heart of Islam, the exhibition actually illustrates the way in which the Hajj represents spatial, temporal and spiritual journeys that combine to create its unique experience. It introduces the subject of Hajj to those for whom it is unfamiliar too and presents it afresh to Muslims who know it better than anyone else. The exhibition portrays the history, the voices of pilgrims and the material culture associated with Hajj together in one place. Running in parallel with the history of Hajj is the story of the material culture that surrounds it, whether paintings evoking the journey; archaeological finds from the Hajj routes; manuscripts, historic photographs and tiles illustrating the holy sanctuaries at Mecca and Medina; certificates and pilgrim guides commemorating the experience; or scientific instruments for determining the direction of Mecca.

Furthermore, there are the objects taken by pilgrims on Hajj or brought back as souvenirs, and the beautiful rare textiles made annually especially for the Ka’bah are also on show. All of these complement and personalise the history, allowing us to glimpse the experience through individuals, deepen our understanding and see how art has been used in the service of Islam. On the other hand, the story of Hajj crosses so many very different disciplines, from religion, history and archaeology to anthropology, travel and art history and so forth. The intensity of the exhibition lies in its efforts to convey the different dimensions of the pilgrimage. This is clear from its beginning when visitors are led through the circular Reading Room of the museum, mirroring the pilgrims' circumambulation of the Ka’bah. Despite the breadth of the information presented, there is a clear and uniting message. The Hajj embraces both the change and constancy of human history, and cannot be separated from its unique fusion of the physical and metaphysical aspects of human existence.

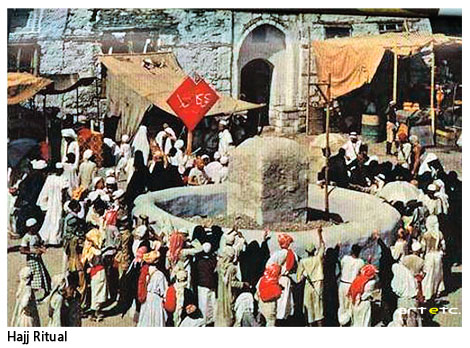

Ritual is an Art of Human Spirituality

The Muslim religious pilgrimage to Mecca, known as the hajj, satisfies the fifth and last pillar of the faith. From its tradition as a pillar of Islam, the word Hajj has applied only to the pilgrimage to Mecca: no pilgrimage to any other place is called Hajj. The Hajj rites are fixed and have been handed down through the ages, and all Muslim pilgrims must fulfill each of the required acts. The pilgrimage consists of a series of rites performed in around the city of Mecca, Saudi Arabia. The rituals of the hajj are perfumed between the 8th and the 13th days of the 12th month (Dhul Hajjah) of the lunar calendar. While some of the rituals, like 'Arafat’, must be performed at a particular time, certain others, like shaving the head or offering sacrifice can be done over a longer period, mostly towards the end of the rituals. In this way the Hajj connects Muslims historically through the generations as well as geographically to other Muslims around the world at any particular time. Hajj is a mesmerizing festival of worship that reflects the unity of all Muslims from all over the world. Unity of Muslims and their aimed bondage of brotherhood is reflected in every single ritual during hajj. It is one of the most important unifying elements in the Muslim community (umma), and it is a journey that marks a huge change in the spiritual and social life of each individual. When one refers to the history of human spirituality, the Hajj is profoundly typical. Long before human beings began to map their world scientifically, they developed a sacred geography. Anything in the natural world that stood out from its surroundings was believed to give human beings direct access to the divine world, because it spoke of something else.1 In that dry region of the Hijaz, the spring of Zamzam may have made Mecca a holy place before a city was built there.2 The life sustaining and purifying qualities of water have always suggested the presence of sacred power. Conversely, sacred places like Mecca and Medina are often associated in this way with the beginnings of life, since they so obviously connect heaven and earth. For instance, in the Islamic world, traditions developed claiming that the Ka’bah is the highest spot on earth, because the polar star shows that it is opposite the centre of the sky;3 that the Ka’bah marks the place where human life began, where the Garden of Eden was located, where Adam named the animals and where all the angels and spirits (except Iblis) bowed down to the first man.4

The Muslim religious pilgrimage to Mecca, known as the hajj, satisfies the fifth and last pillar of the faith. From its tradition as a pillar of Islam, the word Hajj has applied only to the pilgrimage to Mecca: no pilgrimage to any other place is called Hajj. The Hajj rites are fixed and have been handed down through the ages, and all Muslim pilgrims must fulfill each of the required acts. The pilgrimage consists of a series of rites performed in around the city of Mecca, Saudi Arabia. The rituals of the hajj are perfumed between the 8th and the 13th days of the 12th month (Dhul Hajjah) of the lunar calendar. While some of the rituals, like 'Arafat’, must be performed at a particular time, certain others, like shaving the head or offering sacrifice can be done over a longer period, mostly towards the end of the rituals. In this way the Hajj connects Muslims historically through the generations as well as geographically to other Muslims around the world at any particular time. Hajj is a mesmerizing festival of worship that reflects the unity of all Muslims from all over the world. Unity of Muslims and their aimed bondage of brotherhood is reflected in every single ritual during hajj. It is one of the most important unifying elements in the Muslim community (umma), and it is a journey that marks a huge change in the spiritual and social life of each individual. When one refers to the history of human spirituality, the Hajj is profoundly typical. Long before human beings began to map their world scientifically, they developed a sacred geography. Anything in the natural world that stood out from its surroundings was believed to give human beings direct access to the divine world, because it spoke of something else.1 In that dry region of the Hijaz, the spring of Zamzam may have made Mecca a holy place before a city was built there.2 The life sustaining and purifying qualities of water have always suggested the presence of sacred power. Conversely, sacred places like Mecca and Medina are often associated in this way with the beginnings of life, since they so obviously connect heaven and earth. For instance, in the Islamic world, traditions developed claiming that the Ka’bah is the highest spot on earth, because the polar star shows that it is opposite the centre of the sky;3 that the Ka’bah marks the place where human life began, where the Garden of Eden was located, where Adam named the animals and where all the angels and spirits (except Iblis) bowed down to the first man.4

The first entity that experiences some kind of unity during hajj is the pilgrim himself. The hardship of the journey separates them from their ordinary lifestyle: they may have to abstain from sex or abjure any form of violence. The rigours of the road symbolise the difficulty of the ascent; and social norms are subverted, as rich and poor walk together as equals. The pilgrimage is an initiation, a ritualized ordeal that drives participants into a different state of consciousness. Ritual is an art that many of us have lost in the West, and some pilgrims are doubtless more skilled at it than others. The value of a rite does not depend on credulous belief. In traditional society, ritual was not the product of religious ideas; rather, these ideas were the product of ritual. The Sanskrit for a place of pilgrimage is ‘tirtha’, which derives from the root ‘tr’: to ‘cross over’. When they arrive at their destinations, pilgrims perform other rites, carefully crafted to help them make the transition to the divine. For instance, in Mecca, pilgrims re-enact the story of Hagar and Ishmael, walking in the footsteps of Adam, Abraham and Muhammad, they circle the Ka’bah seven times. One can suggest a pilgrimage is just such a ritual. It is a practice that if performed with love, imagination and care, enables people to enter a different, timeless dimension. It liberates us from the surface of our lives. By leaving our ordinary lives behind, turning ourselves physically towards the centre of our world, returning the symbolically to the beginning, submitting ourselves to the demanding rites of Hajj, and living kindly and gently in a properly orientated pilgrim community, we can learn that life has other possibilities. The challenges of the rites can drive us beyond our normal preoccupations into a different state of mind so that, if we have been skilful, mindful pilgrims, we have intimations of something else, a mode of reality that can be never be satisfactorily defined. Maybe in exploring and experiencing the Hajj, therefore we can learn not only about Islam but also to explore the untraveled regions within ourselves.

Moreover, Hajj is a clear manifestation of the unity of the human self and body in complete submission to the One and Only God. During the journey of hajj, the Muslim embarks on a deep spiritual journey which witnesses serious self-denial, where he neglects most of his physical needs, opening the door for his soul to overwhelm his relation with existence and reach a profound climax of joy in submission to Allah, the One and Only God. The Quran (which Muslims believe is the word of God) directs pilgrims towards the concept of unity through a very wise divine order, which says what means:

“There should be no indecent speech, misbehavior, or quarrelling for anyone undertaking the pilgrimage…” (Al-Baqarah 2:197)

Accordingly, the pilgrim needs to understand that the Quran is clearly directing Muslims, who are going for hajj, to drop any manner or attitude that would lead to their division or would result in any kind of dispute. The rituals of hajj smoothly and peacefully take the pilgrims towards the understanding and the experiencing of practical and down-to-earth unity. Then, the Quranic order denies them anything that would cause division or partition. Just like many other nations, some Muslims might go emotional or a bit fanatic about a certain cultural concept, identity, or political view. Differences and disputes might rise and cause division between Muslims. That is where hajj serves best. Hajj is a compelling conference of unity that practically re-directs each pilgrim to his real identity and his first priority: being a Muslim, a brother or sister of all Muslims.

The sense of sharing that prevails during hajj makes the pilgrims focus on what is in common, not on what is different. It provides a calm and comfortable atmosphere that ignores social differences and the diversity of political views and cultural habits. All are one in the eyes of God, standing on the same mount of Arafah, seeking the same end, which is the closeness of God.

The Quran clearly says what means:

“The believers are brothers, so make peace between your two brothers and be mindful of God, so that you may be given mercy.”

(Al-Hujurat 49:10)

Here comes another clear and direct Quranic order related to the unity of Muslims. This should be the general attitude of Muslims. This is intensively reflected through the worship of hajj. It is an expression of love to Allah, being united with the ones who love Him best. In case there is a dispute or division between any two Muslims, or between any two Muslim countries or groups, hajj should be a fair chance to resolve all problems. The outcome of such a peaceful unity is a common joy that prevails and mesmerizes the senses of thousands of pilgrims. Then, the real prize is the absolute forgiveness that each pilgrim receives. Coming down from Mount Arafah, they are all forgiven for sure. Hand in hand, they come down, as pure as a newborn.

The Modern Art of Hajj

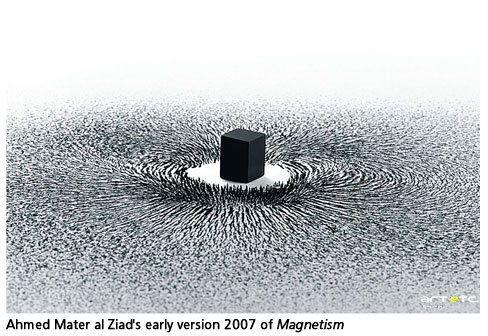

“When my grandfathers spoke to me as a child about their Hajj, they told me of the physical attraction they felt towards the Ka’bah, that they felt drawn to it by an almost magnetic pull”.

-Ahmed Mater al-Ziad

‘The idea is simple and, like its central element, forcefully attractive. Ahmed Mater gives a twist to the magnet and sets in motion tens of thousands of particles of iron that form a single swirling nimbus. Even if we have not taken part in it, we have all seen images of Hajj…Ahmed’s black cuboid magnet is a small simulacrum of the black-draped Ka’bah, the Cube that central elements of the Meccan rites. His circumambulating whirl of metallic filings mirrors in miniature the concentric tawaf of pilgrims and their sevenfold circling of the Ka’bah… [his] magnets and that larger lodestone of pilgrimage can also draw us to things beyond the scale of human existence.’5 The response of artists today in the experience or the concept of Hajj is marked in many ways through photography and other media. Here, three artists are highlighted whose work encapsulates different perspectives of Hajj.

For Mater, magnetism also conveys one of the essential elements of Hajj, that all Muslims are considered the same in the eyes of God whether rich, poor, young or old. As such the iron filings represent a unified body of pilgrims all of whom are similarly attracted to the Ka’bah as the centre of their world.

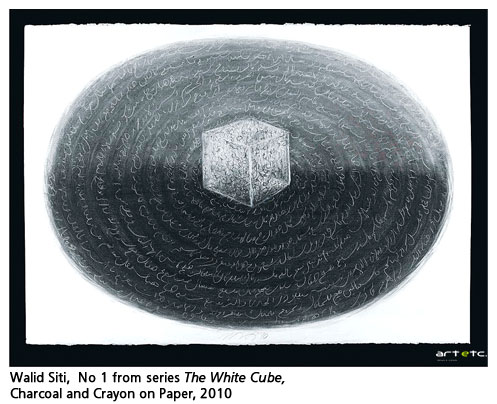

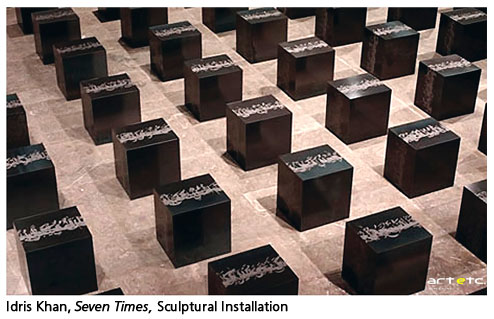

Saudi artist and doctor Ahmed Mater al-Ziad created an early version of Magnetism in 2007. This powerful and evocative installation has been developed into magnets and iron fillings and an accompanying series of photogravures. British artist Idris Khan created a sculptural installation called Seven Times. It is made up of hundred and forty-four steel blocks arranged in a formation that corresponds to the footprint of the Ka’bah (8x8m).6 With prayers sandblasted in layers over the steel blocks, this work was inspired by his father’s Hajj. ‘He felt he had to do it, he wanted to do it. And he changed when he came back, the experience of being there, how overwhelming it was’.7 The Ka’bah inspires Kurdish-Iraqi artist Walid Siti in a different way. The work illustrated here is from a series Precious Stones, in which he highlights the significance of stones to the Kurdish people. For the artist, stones represent the mountains, which Kurds regard as their only friends and the stone of Mecca a focus of prayer and source of solace in a world of conflict and displacement.

Saudi artist and doctor Ahmed Mater al-Ziad created an early version of Magnetism in 2007. This powerful and evocative installation has been developed into magnets and iron fillings and an accompanying series of photogravures. British artist Idris Khan created a sculptural installation called Seven Times. It is made up of hundred and forty-four steel blocks arranged in a formation that corresponds to the footprint of the Ka’bah (8x8m).6 With prayers sandblasted in layers over the steel blocks, this work was inspired by his father’s Hajj. ‘He felt he had to do it, he wanted to do it. And he changed when he came back, the experience of being there, how overwhelming it was’.7 The Ka’bah inspires Kurdish-Iraqi artist Walid Siti in a different way. The work illustrated here is from a series Precious Stones, in which he highlights the significance of stones to the Kurdish people. For the artist, stones represent the mountains, which Kurds regard as their only friends and the stone of Mecca a focus of prayer and source of solace in a world of conflict and displacement.

Reference.

1. Eliade 1958, p.19.

2. Bamyeh 1999, p.36.

3. Wensinck 1916, p.15; Eliade 1958, pp.231, 376.

4. Qur’an 2:30-37; Bennett 1994, p.94.

5. Mackintosh-Smith 2010, p.86.

6. First shown at Victoria Miro Gallery, London, in 2010.

7. Sinclair-Wilson 2011, p.9.