- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- What's Behind This Orange Facade!

- “First you are drawn in by something akin to beauty and then you feel the despair, the cruelty.”

- Art as an Effective Tool against Socio-Political Injustice

- Outlining the Language of Dissent

- Modern Protest Art

- Painting as Social Protest by Indian artists of 1960-s

- Awakening, Resistance and Inversion: Art for Change

- Dadaism

- Peredvizhniki

- A Protected Secret of Contemporary World Art: Japanese Protest Art of 1950s to Early 1970s

- Protest Art from the MENA Countries

- Writing as Transgression: Two Decades of Graffiti in New York Subways

- Goya: An Act of Faith

- Transgressions and Revelations: Frida Kahlo

- The Art of Resistance: The Works of Jane Alexander

- Larissa Sansour: Born to protest?!

- ‘Banksy’: Stencilised Protests

- Journey to the Heart of Islam

- Seven Indian Painters At the Peabody Essex Museum

- Art Chennai 2012 - A Curtain Raiser

- Art Dubai Launches Sixth Edition

- "Torture is Not Art, Nor is Culture" AnimaNaturalis

- The ŠKODA Prize for Indian Contemporary Art 2011

- A(f)Fair of Art: Hope and Despair

- Cross Cultural Encounters

- Style Redefined-The Mercedes-Benz Museum

- Soviet Posters: From the October Revolution to the Second World War

- Masterworks: Jewels of the Collection at the Rubin Museum of Art

- The Mysterious Antonio Stellatelli and His Collections

- Random Strokes

- A ‘Rare’fied Sense of Being Top-Heavy

- The Red-Tape Noose Around India's Art Market

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata, January – February 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Art Bengaluru

- Delhi Dias

- Musings from Chennai

- Preview, February, 2012 – March, 2012

- In the News-February 2012

- Cover

ART news & views

Goya: An Act of Faith

Issue No: 26 Month: 3 Year: 2012

by Nanak Ganguly

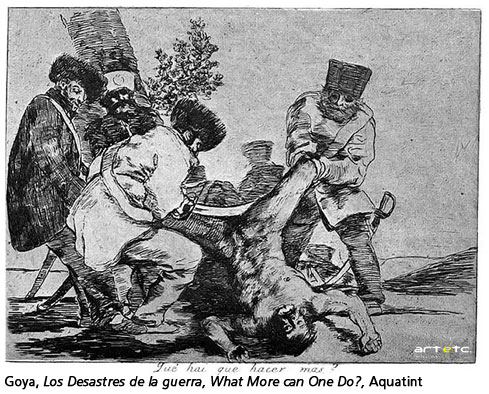

If theory be set aside, in practice neoclassical artists shifted away from life toward a kind of frozen literalism that makes one think that they painted from statues rather than human models. Movements disappeared from their work and with it went the warm flow of colour and line that animated the Rococo and Baroque periods. In its place came formal compositions, heroic in composition, but severe, static, lacking the fanciful delights of the more spontaneous, less intellectualized style that was its enemy. Before Goya, artists often showed war as a heroic, gratifying act of man; on huge canvases, soldiers marched off to marital strains leaving behind cheering populace and adoring ladies. Victory was the attainable goddess, honour, the noble glorifying drive. Goya negated that, in fact he made protests. He was born when Rococo started and lived during the time of Winckelman, the philosopher who was the spokesman for the Neo- classicism on the contrary painted and drew war as it is-honoured by isolated acts of heroism, but more often an inferno that can brutalize man to the point where he commits acts against his fellow beings that exceed the most gruesome imaginings. Goya travelled through Spain sketching what he saw and felt, but it would have been difficult for him to romanticize the Peninsular War even if he had to; the war was fought by both sides with no quarter given or asked. The war against Napoleon in Spain- the Peninsular War, as the English called it, or more simply from the Spanish point of view was the War of Independence that engulfed the entire country. The French tortured and mutilated their prisoners, chopping off limbs and organs woven after the men were dead. The Spaniards reacted in kind, hacking up the bodies of the enemy and subjected captives to long agonizing deaths. Hunger, depravation, misery ravaged Goya’s Spain. The capital Madrid was in a mess. The capital, all diplomats agreed was the dirtiest in Europe and unsafe.

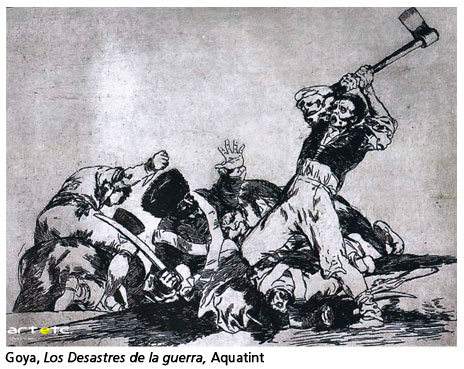

In the history of art often one new art trend broke away and stood defiant against the art of its predecessors. Modern protest art that was initiated probably by the Dada artists who used art as the weapon to criticize the irrational brutality of the World War I has larger social and political connotations engaging with far greater common human good. What did modernity lack that Goya had? Our own age of mass media overloaded with every kind of visual image that all images in some sense were replaceable, a time when few things stood out for long from a prevailing image fog, had something blurred and carried away a part of memorable distinctness the visual icon once had. And Goya was an exception. Through his sketches as early as 200 years back Goya was to create a devastating series of etchings with eloquent and moving titles. The entire collection, published after Goya’s death as The Disasters of War is a profound indictment of war and the atrocities that have always flowed in its wake.

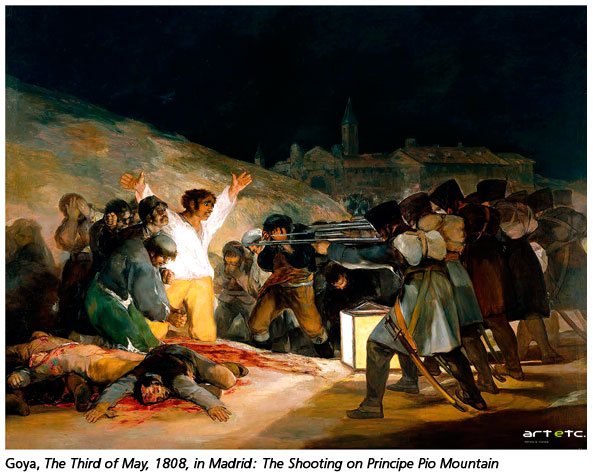

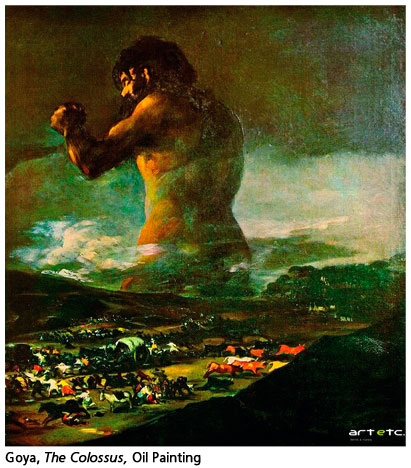

Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes (1746-1828) art has a revolutionary character. His works that are not a bit satirical or hostile have been credited with subversive intent, and much of his work consists of portraits that, fairly seen, are not in the least derogatory of those who commissioned them. The idea of Goya as an artist “naturally ‘agin’ the system” is pretty much a modernist myth. But it is based on a fundamental truth of his character- he was a man of great and at times heroic independence, who never betrayed his deep impulses or depicted a pictorial lie and was exceptionally productive with some seven hundred paintings, nine hundred drawings, and almost three hundred prints, two great mural cycles. Goya’s work evokes the unique Spanish pessimism about a man’s fallen state. It is a feeling so profound as to prelude all faith in political, social or economic progress, and ordained to regard all temporal leaders irrelevant at best and comically at worst. “With him you have the beginnings of a modern anarchy.” Art Historian Bernard Berenson said when he viewed an exhibition of Goya’s work. “And now modern painting begins,” remarked Andre Malraux. Goya’s time in Spanish history – the late 18th and early 19th centuries was a period of tumult. Disorientation, alienation, fragmentation despair, these are for the individual, the seemingly inevitable by-products of sweeping attempts of social realignment, and they are Goya’s real subjects. Goya was 62 years old, already a respected and wealthy court painter when political intrigue precipitated on Spain a cruel and unnecessary war which eventually became the backdrop for the work whose vivid truth would help him to secure as one of the world’s great artists. Napoleon seizing the advantage of squabble in the Spanish ruling family took the throne himself and solidified his troop positions in Madrid thus setting stage for a rebellion that would lead to war lasting six vicious years. The terror, chaos and grim foreboding that loomed over Spain during the Napoleonic wars of 1808-14 are depicted in the paintings of Goya. In the Colossus done in 1811 the frightened populace dashes madly about on the ground, the Colossus perhaps representing war itself dominates the sky. The most intriguing one that depicts the horrific side of war is The Third of May, 1808, in Madrid: the Shooting on Principe Pio Mountain done in 1814. In Madrid on May 2, 1808, rumours swept the uneasy capital. The royal family of Spain was to be kidnapped and murdered. At the Puerta del Sol near the palace, a large crowd gathered which became restive. Suddenly the mood became hostile and the mob surged forward against the French guards. The Spaniards were raked with fusillades of bullets and French reinforcements were dispatched, including the Mamluks the despised Egyptian mercenaries. But the mob assault continued, as soldiers were pulled from their horses and attacked with knives and bare hands. It is not known whether Goya witnessed the uprising, but when he commemorated six years later, he imparted a passionate immediacy that makes it seem as he had been there.

Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes (1746-1828) art has a revolutionary character. His works that are not a bit satirical or hostile have been credited with subversive intent, and much of his work consists of portraits that, fairly seen, are not in the least derogatory of those who commissioned them. The idea of Goya as an artist “naturally ‘agin’ the system” is pretty much a modernist myth. But it is based on a fundamental truth of his character- he was a man of great and at times heroic independence, who never betrayed his deep impulses or depicted a pictorial lie and was exceptionally productive with some seven hundred paintings, nine hundred drawings, and almost three hundred prints, two great mural cycles. Goya’s work evokes the unique Spanish pessimism about a man’s fallen state. It is a feeling so profound as to prelude all faith in political, social or economic progress, and ordained to regard all temporal leaders irrelevant at best and comically at worst. “With him you have the beginnings of a modern anarchy.” Art Historian Bernard Berenson said when he viewed an exhibition of Goya’s work. “And now modern painting begins,” remarked Andre Malraux. Goya’s time in Spanish history – the late 18th and early 19th centuries was a period of tumult. Disorientation, alienation, fragmentation despair, these are for the individual, the seemingly inevitable by-products of sweeping attempts of social realignment, and they are Goya’s real subjects. Goya was 62 years old, already a respected and wealthy court painter when political intrigue precipitated on Spain a cruel and unnecessary war which eventually became the backdrop for the work whose vivid truth would help him to secure as one of the world’s great artists. Napoleon seizing the advantage of squabble in the Spanish ruling family took the throne himself and solidified his troop positions in Madrid thus setting stage for a rebellion that would lead to war lasting six vicious years. The terror, chaos and grim foreboding that loomed over Spain during the Napoleonic wars of 1808-14 are depicted in the paintings of Goya. In the Colossus done in 1811 the frightened populace dashes madly about on the ground, the Colossus perhaps representing war itself dominates the sky. The most intriguing one that depicts the horrific side of war is The Third of May, 1808, in Madrid: the Shooting on Principe Pio Mountain done in 1814. In Madrid on May 2, 1808, rumours swept the uneasy capital. The royal family of Spain was to be kidnapped and murdered. At the Puerta del Sol near the palace, a large crowd gathered which became restive. Suddenly the mood became hostile and the mob surged forward against the French guards. The Spaniards were raked with fusillades of bullets and French reinforcements were dispatched, including the Mamluks the despised Egyptian mercenaries. But the mob assault continued, as soldiers were pulled from their horses and attacked with knives and bare hands. It is not known whether Goya witnessed the uprising, but when he commemorated six years later, he imparted a passionate immediacy that makes it seem as he had been there.

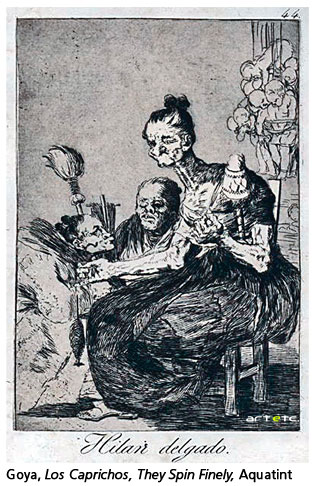

If one were to look at Goya’s paintings and aquatints titled The Disasters of War on the Peninsular War, of his last few years one would find the strategy of subversion worked carefully into almost all their manifest attributes. It follows fastidiously posited ‘inspite of’ codes of brutality and suffering. The viewer strays into them as if in half remembrance, unanchored, almost without a narrative, works that seem particularly legitimate and self assured. A fast pace suited his temperament. He was capable of the most delicate brushwork, particularly when working with flesh tones and textures. On close examination the faces of one of his portrait subjects blurred and out of focus, and neither the definitive line of a wrinkle nor the trace of the artist’s brush can be discerned, it is as if Goya had found a way of rendering the imperceptible movement of breathing. But his most characteristic stroke was short, rapid, fairly heavy and rather nervous. Even some of the inquisition drawings depict its tortures. The torture images are sometimes linked to noted historical persons who fell into the Inquisition’s hands. Not everyone in Inquisition drawings is being tortured. Some are merely humiliated, exposed, or otherwise mistreated without violence. In art history what Rembrandt did to etchings was Goya to aquatints. One pieces together stories that had been interred long ago and could no longer be told unless you open up new signs. Instead of strands, one holds on to the textures in a vast middle of broken vectors; the substance of a wakeful dream materializing image and reality, dream and component made by teasing paint and pigment beguiling the viewer into a seemingly no-win game of illusion and recognition of many beginnings and no end of human suffering and bestiality especially the scars a war leaves behind in its aftermath. Goya in these aquatints and drawings employs a subjective apparatus not as a passive spectator but as a critical insider who controls the ‘plot’ through the very media of realism which he employs to realize them. Those deep, thick, mysterious black figures which appear in his aquatints entitled Los Caprichos, with solidity and certainty, and yet with such apparitional strangeness, that darkness in which most detail is lost, so that one’s eye moves into record of states of mind rather than a description of “real” world –such effects owe their intensity to the aquatint medium, and might not have been available to Goya without it. These are made under the threat of potential loss, and this does not always resolve itself in the artist’s favour permeated by an undeniable sense of sadness, and awareness of the anguish, frailty and impermanence of life. He makes pictorial and aesthetic sense out of a personal despair and its experience of a torn and injured world. And yet the energy, intensity, romanticism and sensuousness of the way they are painted provide a celebratory transcendence of the subject matter. But more than that like the Los caprichos or Disparates, the ‘Black Paintings’ reveal some of Goya’s uncanny observation of human folly in action. But more than that, they expose his intense awareness of the dark forces of panic, terror, fear, and hysteria, - the all too real ingredients of the human experience. The conflict at the Puerta del Sol might not have been enough to start a war, but the next day the French committed a blunder that made war inevitable. The French troop executed, without a trial, all Spaniards believe to have been connected in any way with the uprising. Goya, painting the firing squad six years later, emerged with his most gripping, dramatic masterpiece. The executioners are anonymous soldiers. Doggedly obeying the orders by killing the suspects lined up before them. The focus of the painting is a peasant with arms upraised, his face and posture a mixture of horror, pride and resignation in the face of death. The volleys from the French firing squads rang throughout Goya’s homeland. Across, the land, fighting guerillas (the word, meaning little wars, was coined at this time) threw themselves on the French soldiers in an impassioned display of nationalistic fury. Though an admirer of French Enlightenment he recorded the war’s brutality and illogic of it must have strained his sense of reason drenched with his love for Spain. For Goya the act of painting was instrument of freedom.

If one were to look at Goya’s paintings and aquatints titled The Disasters of War on the Peninsular War, of his last few years one would find the strategy of subversion worked carefully into almost all their manifest attributes. It follows fastidiously posited ‘inspite of’ codes of brutality and suffering. The viewer strays into them as if in half remembrance, unanchored, almost without a narrative, works that seem particularly legitimate and self assured. A fast pace suited his temperament. He was capable of the most delicate brushwork, particularly when working with flesh tones and textures. On close examination the faces of one of his portrait subjects blurred and out of focus, and neither the definitive line of a wrinkle nor the trace of the artist’s brush can be discerned, it is as if Goya had found a way of rendering the imperceptible movement of breathing. But his most characteristic stroke was short, rapid, fairly heavy and rather nervous. Even some of the inquisition drawings depict its tortures. The torture images are sometimes linked to noted historical persons who fell into the Inquisition’s hands. Not everyone in Inquisition drawings is being tortured. Some are merely humiliated, exposed, or otherwise mistreated without violence. In art history what Rembrandt did to etchings was Goya to aquatints. One pieces together stories that had been interred long ago and could no longer be told unless you open up new signs. Instead of strands, one holds on to the textures in a vast middle of broken vectors; the substance of a wakeful dream materializing image and reality, dream and component made by teasing paint and pigment beguiling the viewer into a seemingly no-win game of illusion and recognition of many beginnings and no end of human suffering and bestiality especially the scars a war leaves behind in its aftermath. Goya in these aquatints and drawings employs a subjective apparatus not as a passive spectator but as a critical insider who controls the ‘plot’ through the very media of realism which he employs to realize them. Those deep, thick, mysterious black figures which appear in his aquatints entitled Los Caprichos, with solidity and certainty, and yet with such apparitional strangeness, that darkness in which most detail is lost, so that one’s eye moves into record of states of mind rather than a description of “real” world –such effects owe their intensity to the aquatint medium, and might not have been available to Goya without it. These are made under the threat of potential loss, and this does not always resolve itself in the artist’s favour permeated by an undeniable sense of sadness, and awareness of the anguish, frailty and impermanence of life. He makes pictorial and aesthetic sense out of a personal despair and its experience of a torn and injured world. And yet the energy, intensity, romanticism and sensuousness of the way they are painted provide a celebratory transcendence of the subject matter. But more than that like the Los caprichos or Disparates, the ‘Black Paintings’ reveal some of Goya’s uncanny observation of human folly in action. But more than that, they expose his intense awareness of the dark forces of panic, terror, fear, and hysteria, - the all too real ingredients of the human experience. The conflict at the Puerta del Sol might not have been enough to start a war, but the next day the French committed a blunder that made war inevitable. The French troop executed, without a trial, all Spaniards believe to have been connected in any way with the uprising. Goya, painting the firing squad six years later, emerged with his most gripping, dramatic masterpiece. The executioners are anonymous soldiers. Doggedly obeying the orders by killing the suspects lined up before them. The focus of the painting is a peasant with arms upraised, his face and posture a mixture of horror, pride and resignation in the face of death. The volleys from the French firing squads rang throughout Goya’s homeland. Across, the land, fighting guerillas (the word, meaning little wars, was coined at this time) threw themselves on the French soldiers in an impassioned display of nationalistic fury. Though an admirer of French Enlightenment he recorded the war’s brutality and illogic of it must have strained his sense of reason drenched with his love for Spain. For Goya the act of painting was instrument of freedom.

How does one wade across these somnolent sloughs, the sparse and effacive grounds that make him one the greatest graphic artist world has ever known. Where all our leads are buried? Along with the modernist techniques he foregrounds other devices to celebrate the surface, illuminating, inexorably bringing to life, tending a surface he fears might dull. The visual parable is construed on an imaginary triangle whose matrices are represented by the audience, himself and those individuals who serve as the protagonists of his paintings. Similar to Italo Calvino’s bodyless soldier’s journey on the boundaryless maps that facilitates him with two important kinds of visuals: the static and the mobile. Goya situates his subjects in a way that capture these points of coincidence through canny editing, through vantage, through the choice of detail and through the deployment of figures in space. His ability to conjure up experience through colour and through the shape and weight of lines and rhythms of composition are eloquent. One senses a working out of pictorial conventions, of attitudes and of free associations that swivel between dream and reality. The works have a nervous, inchoate narrative quality, as figures, both wraiths like and robust, take on symbolic weight as they get filtered through liquid swells and flows of translucent colours. A man stands under a vast canvas and against it and in it (Los desastres, sad forebodings of what had to happen). Not so much in profile as in a look-away effort that annuls, silhouette against an evening light, impossibly, all lines of gaze. A slow, sonorous muffle blows across the air. One hears also an uncertain wind build up and, then, drop. Does it seem that these figures had once been out of reference; an absence that no longer is? It is a long line of flight that Master creates because we are tracing the real and composing a plane of consistency, not simply imaging or dreaming. The primacy of the lines of flight must not be understood in a chronological sense, or in the sense of an eternal generality. Rather, it points towards the ‘untimely’ as fact and principle; a time without rhythm, a haecceity like a wind that stirs at midnight, or at noon or dusk. It is vulnerable like an upturned inscription; but also, resolute like an image that refuses the journey across the mind’s aperture in a stop-go movement- a realist balance that has long ceased to be a picture-fable. Among the Inquisition drawings a woman slumps against a wooden structure, maybe part of a scaffold. Her ankles are locked by a wooden bar. Her arms are behind her back. Her dress is torn and crumpled, her hair disheveled, her expression drained, her mouth slack. What kind of hell Goya does not say. The images here refuse to disavow their own separation in a narrative splurge. They create their own untimely rhythm in order not to eschew the real to pitch their sanity in a new political sign keeping the viewer on the edge. How will the pure sound stand against the predictable phrase? Affection against power, the Spanish Master negotiates ‘the great ruptures and oppositions’ pitching one orality against another. But does one negotiate ‘the little cracks and imperceptible ruptures that come from the south’ and do not have definable orality as yet? However the two women in “And this as well” at dusk, nothing is completely lost. Their bodies luminesce through earth, silhouetted shadow, as a patch of light touches their hair and lives precisely in its recesses creating a spatial paradox, almost sensuously. One sees the impending darkness like a swirl, a slow sonorous muffle blows across the night. One hears also an uncertain wind build up and then, drop and as the brooding images shuffle across the painted screen, they seem to offer an increasingly diminishing possibility of pat interpretation which gives the work its haunting edge. In this aquatint done in 1863, the element which was once provided by iconography now springs largely out of his expressive handling. And he employs a palette which, if not fluorescent, is keyed up almost to that level, again denying any realism. “Its every line aim at its destination; each patch of tone vibrates with its neighbour, the open spaces work with (sublime) energy” (-Leo Steinberg) and evades the blunt of thing to flirt with its margins. The figures inhabit dream like settings- that suddenly appear, as landscapes that abrupt open up to reveal a different landscape, boundaries are abolished, and even the familiar is subjected to interrogation and begins to take on the aspect of the mythic. Goya creates a metaphor for his own activity. It is almost a combat. It is the same thing for suffering: in such suffering there is a whole manouevre of the unconscious of the soul, of the body, that makes us come to bear the unbearable. Goya’s etching clearly reveals how he liked to explore, reuse, and recycle poses, sometimes for rather different ends. Each stroke, each line of Goya’s work has survived the shipwreck of living to tell at tale and as if it’s time to paint for him all the phenomena on the canvas before they are precipitated, assembled, crystallized. The power with which Goya could infuse a still life is best seen in his Dead Turkey. It is just that a bird propped up against a coarsely woven wicker basket, in which every protuberance of the weave is rendered by a single stroke of round brush with brusque skill that might have made any Master painter envious. But the bird itself had an extraordinary vitality, if ‘vitality’ is a word that can be associated with depiction of something as irrevocably dead as Goya’s turkey. It is an odd paradox. He records, in what we feel to be a coolly objective way, a shocking experience of life, as it occurs somewhat behind the face, as it might return at night to one who thought he had escaped and blessedly forgotten it-returning intact, worse, more dangerously connected, more deeply involved with friend and enemy, more open to things beyond the soul’s search as a distorted mask, a blank deadpan face, or a dream shout that stays in the waking mind as a lumpish beast crouched there on the threshold (-The Dead Turkey). Apart from this startling, sinister beauty, there is something more than style, something other than the masterful technical expertise that gives his image the foot –poundage of its striking power and penetration as in his Inquisition album “Por liberal?”(for being a liberal). But more and more strongly, dredging up some surrealistic subconscious visualizing the possibility of a tangible object, yet defies identification. Quiet enigmas of subtle counterpoint, their viewings result not in familiarity but in fresh discoveries. In the end it makes us seek his work out as if we needed it, and makes us cherish it, as some source of elixir, long after more documentary or photographic evidence of “our common suffering” has become a sad blur. These more than anything else in the show bring us close to his greatest work. Something of the same quality is transmitted- an oddness, a disturbing quiet, a sense of being in a room with a Master who insists on being with us in halls of Prado, whose last life was lived out under the shadows of a crippling disability that must have made him suspicious, cranky and overcompensate for loneliness but protests he made through his work again and again to make this world a better place for mankind.

How does one wade across these somnolent sloughs, the sparse and effacive grounds that make him one the greatest graphic artist world has ever known. Where all our leads are buried? Along with the modernist techniques he foregrounds other devices to celebrate the surface, illuminating, inexorably bringing to life, tending a surface he fears might dull. The visual parable is construed on an imaginary triangle whose matrices are represented by the audience, himself and those individuals who serve as the protagonists of his paintings. Similar to Italo Calvino’s bodyless soldier’s journey on the boundaryless maps that facilitates him with two important kinds of visuals: the static and the mobile. Goya situates his subjects in a way that capture these points of coincidence through canny editing, through vantage, through the choice of detail and through the deployment of figures in space. His ability to conjure up experience through colour and through the shape and weight of lines and rhythms of composition are eloquent. One senses a working out of pictorial conventions, of attitudes and of free associations that swivel between dream and reality. The works have a nervous, inchoate narrative quality, as figures, both wraiths like and robust, take on symbolic weight as they get filtered through liquid swells and flows of translucent colours. A man stands under a vast canvas and against it and in it (Los desastres, sad forebodings of what had to happen). Not so much in profile as in a look-away effort that annuls, silhouette against an evening light, impossibly, all lines of gaze. A slow, sonorous muffle blows across the air. One hears also an uncertain wind build up and, then, drop. Does it seem that these figures had once been out of reference; an absence that no longer is? It is a long line of flight that Master creates because we are tracing the real and composing a plane of consistency, not simply imaging or dreaming. The primacy of the lines of flight must not be understood in a chronological sense, or in the sense of an eternal generality. Rather, it points towards the ‘untimely’ as fact and principle; a time without rhythm, a haecceity like a wind that stirs at midnight, or at noon or dusk. It is vulnerable like an upturned inscription; but also, resolute like an image that refuses the journey across the mind’s aperture in a stop-go movement- a realist balance that has long ceased to be a picture-fable. Among the Inquisition drawings a woman slumps against a wooden structure, maybe part of a scaffold. Her ankles are locked by a wooden bar. Her arms are behind her back. Her dress is torn and crumpled, her hair disheveled, her expression drained, her mouth slack. What kind of hell Goya does not say. The images here refuse to disavow their own separation in a narrative splurge. They create their own untimely rhythm in order not to eschew the real to pitch their sanity in a new political sign keeping the viewer on the edge. How will the pure sound stand against the predictable phrase? Affection against power, the Spanish Master negotiates ‘the great ruptures and oppositions’ pitching one orality against another. But does one negotiate ‘the little cracks and imperceptible ruptures that come from the south’ and do not have definable orality as yet? However the two women in “And this as well” at dusk, nothing is completely lost. Their bodies luminesce through earth, silhouetted shadow, as a patch of light touches their hair and lives precisely in its recesses creating a spatial paradox, almost sensuously. One sees the impending darkness like a swirl, a slow sonorous muffle blows across the night. One hears also an uncertain wind build up and then, drop and as the brooding images shuffle across the painted screen, they seem to offer an increasingly diminishing possibility of pat interpretation which gives the work its haunting edge. In this aquatint done in 1863, the element which was once provided by iconography now springs largely out of his expressive handling. And he employs a palette which, if not fluorescent, is keyed up almost to that level, again denying any realism. “Its every line aim at its destination; each patch of tone vibrates with its neighbour, the open spaces work with (sublime) energy” (-Leo Steinberg) and evades the blunt of thing to flirt with its margins. The figures inhabit dream like settings- that suddenly appear, as landscapes that abrupt open up to reveal a different landscape, boundaries are abolished, and even the familiar is subjected to interrogation and begins to take on the aspect of the mythic. Goya creates a metaphor for his own activity. It is almost a combat. It is the same thing for suffering: in such suffering there is a whole manouevre of the unconscious of the soul, of the body, that makes us come to bear the unbearable. Goya’s etching clearly reveals how he liked to explore, reuse, and recycle poses, sometimes for rather different ends. Each stroke, each line of Goya’s work has survived the shipwreck of living to tell at tale and as if it’s time to paint for him all the phenomena on the canvas before they are precipitated, assembled, crystallized. The power with which Goya could infuse a still life is best seen in his Dead Turkey. It is just that a bird propped up against a coarsely woven wicker basket, in which every protuberance of the weave is rendered by a single stroke of round brush with brusque skill that might have made any Master painter envious. But the bird itself had an extraordinary vitality, if ‘vitality’ is a word that can be associated with depiction of something as irrevocably dead as Goya’s turkey. It is an odd paradox. He records, in what we feel to be a coolly objective way, a shocking experience of life, as it occurs somewhat behind the face, as it might return at night to one who thought he had escaped and blessedly forgotten it-returning intact, worse, more dangerously connected, more deeply involved with friend and enemy, more open to things beyond the soul’s search as a distorted mask, a blank deadpan face, or a dream shout that stays in the waking mind as a lumpish beast crouched there on the threshold (-The Dead Turkey). Apart from this startling, sinister beauty, there is something more than style, something other than the masterful technical expertise that gives his image the foot –poundage of its striking power and penetration as in his Inquisition album “Por liberal?”(for being a liberal). But more and more strongly, dredging up some surrealistic subconscious visualizing the possibility of a tangible object, yet defies identification. Quiet enigmas of subtle counterpoint, their viewings result not in familiarity but in fresh discoveries. In the end it makes us seek his work out as if we needed it, and makes us cherish it, as some source of elixir, long after more documentary or photographic evidence of “our common suffering” has become a sad blur. These more than anything else in the show bring us close to his greatest work. Something of the same quality is transmitted- an oddness, a disturbing quiet, a sense of being in a room with a Master who insists on being with us in halls of Prado, whose last life was lived out under the shadows of a crippling disability that must have made him suspicious, cranky and overcompensate for loneliness but protests he made through his work again and again to make this world a better place for mankind.