- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- What's Behind This Orange Facade!

- “First you are drawn in by something akin to beauty and then you feel the despair, the cruelty.”

- Art as an Effective Tool against Socio-Political Injustice

- Outlining the Language of Dissent

- Modern Protest Art

- Painting as Social Protest by Indian artists of 1960-s

- Awakening, Resistance and Inversion: Art for Change

- Dadaism

- Peredvizhniki

- A Protected Secret of Contemporary World Art: Japanese Protest Art of 1950s to Early 1970s

- Protest Art from the MENA Countries

- Writing as Transgression: Two Decades of Graffiti in New York Subways

- Goya: An Act of Faith

- Transgressions and Revelations: Frida Kahlo

- The Art of Resistance: The Works of Jane Alexander

- Larissa Sansour: Born to protest?!

- ‘Banksy’: Stencilised Protests

- Journey to the Heart of Islam

- Seven Indian Painters At the Peabody Essex Museum

- Art Chennai 2012 - A Curtain Raiser

- Art Dubai Launches Sixth Edition

- "Torture is Not Art, Nor is Culture" AnimaNaturalis

- The ŠKODA Prize for Indian Contemporary Art 2011

- A(f)Fair of Art: Hope and Despair

- Cross Cultural Encounters

- Style Redefined-The Mercedes-Benz Museum

- Soviet Posters: From the October Revolution to the Second World War

- Masterworks: Jewels of the Collection at the Rubin Museum of Art

- The Mysterious Antonio Stellatelli and His Collections

- Random Strokes

- A ‘Rare’fied Sense of Being Top-Heavy

- The Red-Tape Noose Around India's Art Market

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata, January – February 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Art Bengaluru

- Delhi Dias

- Musings from Chennai

- Preview, February, 2012 – March, 2012

- In the News-February 2012

- Cover

ART news & views

Modern Protest Art

Issue No: 26 Month: 3 Year: 2012

by Tanya Abraham

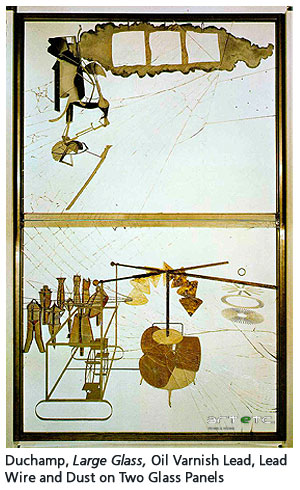

If art is a form of expression, then the thought of using it as a medium depends wholly on the idea behind its projection. With modernism, came art in its many forms of use – and one of its emergences being a medium of expression as art that protests. And thus it has been noted as a ‘visual means of protest’ which has a silent but deep impact upon the minds of viewers - The result being far superior to common forms of action against a certain idea or ideology, which allows minds to think and delve deeper into the nuances of the protest and in its projection. And thus we come back to the idea that underlines art, for only the idea behind an artwork can rake up the necessary reaction to a subject, which being the core of the subject requires for it to be interesting. For, it is this interest that lures the public and creates the needed change. And thus, in many ways [modern] protest art is a silent yet powerful form of action that has created the necessary results: Donald Judd declared [1965] that ‘the central aims of art is to create artworks capable of provoking intense awareness.’ How this art is projected depends solely on the artist [the material used, the environment in which it is displayed], but what comes out of it or the impact it has on the viewer is what makes art [in this case and especially protest art] successful. This was further pointed out by Marcel Duchamp who insisted that ‘the concept of art must always precede the artwork.’ And thus, many have been aghast at ideas that move into planes quite unfathomable – Like in the case of Duchamp’s The Large Glass which shattered in transit to which the artist simply stated that his work had not been destroyed but changed to take upon a different form: He did not adhere to the idea that artists can give the final form to an artwork, to him it was the idea alone which was important. Ideas thus remain at the core of authentic art. And artists who began breaking away from conventional practices looked towards depicting the idea and using it in meaningful arenas, in this case as a means to object. [For example, the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1970 came up with an exhibition titled Information propagating that the concept is what is important over solid form.] Emphasising this Lewitt wrote [in 1967], ‘the idea or the concept is most important aspect of the work, all planning and decision[s] are made beforehand and the execution is a prefunctionary affair. The idea becomes the machine that makes the art.’ And so the idea which is used and propelled is the foundation of art, especially when used to assert a point. If there is no idea, then art renders meaningless and lies barren, becoming useless in its agenda.

If art is a form of expression, then the thought of using it as a medium depends wholly on the idea behind its projection. With modernism, came art in its many forms of use – and one of its emergences being a medium of expression as art that protests. And thus it has been noted as a ‘visual means of protest’ which has a silent but deep impact upon the minds of viewers - The result being far superior to common forms of action against a certain idea or ideology, which allows minds to think and delve deeper into the nuances of the protest and in its projection. And thus we come back to the idea that underlines art, for only the idea behind an artwork can rake up the necessary reaction to a subject, which being the core of the subject requires for it to be interesting. For, it is this interest that lures the public and creates the needed change. And thus, in many ways [modern] protest art is a silent yet powerful form of action that has created the necessary results: Donald Judd declared [1965] that ‘the central aims of art is to create artworks capable of provoking intense awareness.’ How this art is projected depends solely on the artist [the material used, the environment in which it is displayed], but what comes out of it or the impact it has on the viewer is what makes art [in this case and especially protest art] successful. This was further pointed out by Marcel Duchamp who insisted that ‘the concept of art must always precede the artwork.’ And thus, many have been aghast at ideas that move into planes quite unfathomable – Like in the case of Duchamp’s The Large Glass which shattered in transit to which the artist simply stated that his work had not been destroyed but changed to take upon a different form: He did not adhere to the idea that artists can give the final form to an artwork, to him it was the idea alone which was important. Ideas thus remain at the core of authentic art. And artists who began breaking away from conventional practices looked towards depicting the idea and using it in meaningful arenas, in this case as a means to object. [For example, the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1970 came up with an exhibition titled Information propagating that the concept is what is important over solid form.] Emphasising this Lewitt wrote [in 1967], ‘the idea or the concept is most important aspect of the work, all planning and decision[s] are made beforehand and the execution is a prefunctionary affair. The idea becomes the machine that makes the art.’ And so the idea which is used and propelled is the foundation of art, especially when used to assert a point. If there is no idea, then art renders meaningless and lies barren, becoming useless in its agenda.

This can be seen in the 1960’s as artists and art critics questioned the idea behind art works. Much of this came from the socio-economic changes that were happening in USA and Europe, as students, labourers, social and civic right activists voiced opinions against existing socio-economic situations in the west. This change led to a questioning of even art, demanding an explanation of the reason behind an art form – the public protested, and this public were artists and art aficionados. Thus, Performance, Video, Graffiti and Body art began to be embraced as progressive artists rejected conventional works and demanded an explanation behind existing values. It thus saw the emergence of a new aesthetic development, both of values and values in art. Art no longer remained within set parameters, developed for and by a certain thinking pattern. Instead it broke free and it allowed ideas to flow freely and in this creation of new ideas, it raised a means to express.

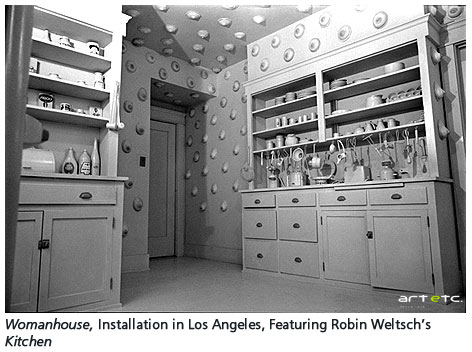

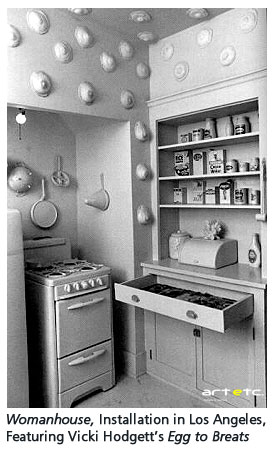

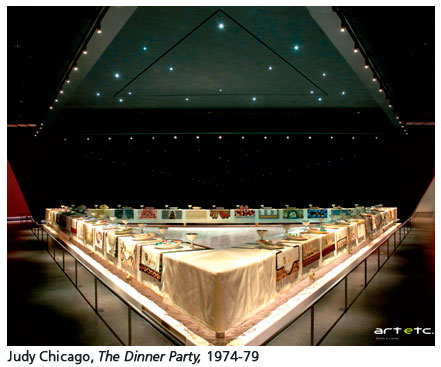

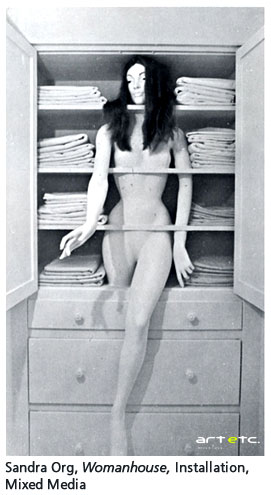

Thus ideas began to be used, questioned and expanded upon. Art became a means of and for protest - Many times protest which was individual and other times protest that was social. And thus concepts were moved to an arena of radical change, radical thought and radical wants. We see this in the 1960s as feminist movements in Europe and North America used body art to throw voice upon equality and highlight sexual discrimination. They used mediums which were closely associated with women all over the world, to express their opinions such as those connected to household work or other domestic duties. Thus, consciousness awareness was a major objective. Programmes [such as the Feminist Arts Programme at the California State University] worked at allowing female artists to openly and freely project art that aided their own personal and social needs. Thus, in 1972 Womanhouse at the California Institute of Arts challenged spaces linked to a domestic ambience through art works: A striking one was of a bride who moved down the staircase and into the kitchen, her magnificent train getting dirty on the way. She was decorated with brightly coloured breasts that were then dropped into the frying pan to form fried eggs! Another was of a woman trapped in a clothes closet [by artist Sandra Org [mixed media]], which contributed greatly to offer a new platform for social expression. Womanhouse was a great path-breaker for women artists, who were encouraged ‘to speak’, to use art to express a thought or an idea. It seemed a fantastic way for the marginalised to protest silently, speaking on behalf of women all over the world: Judy Chicago’s Dinner Party [1974-79] uses china and needlework to express feminity, now displayed at the Brooklyn Museum’s section for Feminist Art. The work is intense and extremely thought provoking, so much that it is arranged as a triangle, a symbol of womanhood. She has inscribed the names of 999 women on the floor [from Frida Kahlo to Isadora Duncan, for example], while the table has thirteen seats [like the Last Supper which depicts a male oriented event], and the plates are decorated with symbols based on the female genitalia. This is a strong and pure example of protesting an existing pattern or social structure in ways which are so blatant as well as intelligent, it is bound to throw open a discussion which has deep intended effects.

Thus ideas began to be used, questioned and expanded upon. Art became a means of and for protest - Many times protest which was individual and other times protest that was social. And thus concepts were moved to an arena of radical change, radical thought and radical wants. We see this in the 1960s as feminist movements in Europe and North America used body art to throw voice upon equality and highlight sexual discrimination. They used mediums which were closely associated with women all over the world, to express their opinions such as those connected to household work or other domestic duties. Thus, consciousness awareness was a major objective. Programmes [such as the Feminist Arts Programme at the California State University] worked at allowing female artists to openly and freely project art that aided their own personal and social needs. Thus, in 1972 Womanhouse at the California Institute of Arts challenged spaces linked to a domestic ambience through art works: A striking one was of a bride who moved down the staircase and into the kitchen, her magnificent train getting dirty on the way. She was decorated with brightly coloured breasts that were then dropped into the frying pan to form fried eggs! Another was of a woman trapped in a clothes closet [by artist Sandra Org [mixed media]], which contributed greatly to offer a new platform for social expression. Womanhouse was a great path-breaker for women artists, who were encouraged ‘to speak’, to use art to express a thought or an idea. It seemed a fantastic way for the marginalised to protest silently, speaking on behalf of women all over the world: Judy Chicago’s Dinner Party [1974-79] uses china and needlework to express feminity, now displayed at the Brooklyn Museum’s section for Feminist Art. The work is intense and extremely thought provoking, so much that it is arranged as a triangle, a symbol of womanhood. She has inscribed the names of 999 women on the floor [from Frida Kahlo to Isadora Duncan, for example], while the table has thirteen seats [like the Last Supper which depicts a male oriented event], and the plates are decorated with symbols based on the female genitalia. This is a strong and pure example of protesting an existing pattern or social structure in ways which are so blatant as well as intelligent, it is bound to throw open a discussion which has deep intended effects.

This sort of protest art then moved to newer spheres, as women artists used this opening to develop knowledge and allow a change in everyday life. Mary Kelly’s post-partum Document talks about her as a new mother and her work has imprints of medical and educational records, diaper stains etc- she used psychology [she based her work on the linguistic interpretations of Freud] to explore female experiences which were ignored or shunned into oblivion. By 1985, protest art by women moved into another stage as ‘Guerrilla Girls’ [anonymous feminists] made public experiences in gorilla masks to protest against the few women artists who were allowed to showcase their works in galleries or exhibited at museums – they made public appearances to question the conscience of the art world. They protested by using posters in cities, renting billboard space, publishing books and the like.

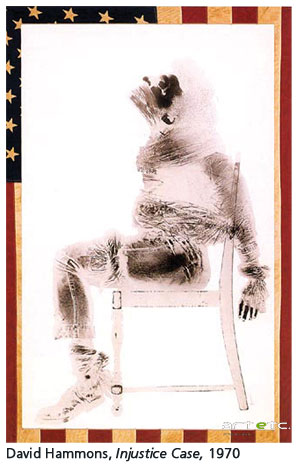

Not just feminist art, but socio-economic issues also found release through visual art. For example, a strong protest regarding African-Americans came about in 1967 with the Wall of Respect organized in Chicago by the Organization of Black American Culture. They, using visual art, had a tremendous and long lasting effect on the issue they protested, where a wall became a mural which was created by artists and residents of the area, which depicted many Black heroes. This became a base for more [protest] developments of this kind. Such social and political protests also came from individual artists and not a group or an organization per se - David Hammons used art to blatantly project his thoughts – His Injustice Case shows a captive tied to a chair, who could be a prisoner stating that America is not just in all cases, explicitly throwing light upon the injustices the country does. Also, Hammons public art work called the Higher Goals has a multitude of shiny bottle caps on telephone poles and a basketball at the top of the poles, explaining street life in terms of the youth – the lack of an education and what basketball has been doing to the Black community of his time.

Not just feminist art, but socio-economic issues also found release through visual art. For example, a strong protest regarding African-Americans came about in 1967 with the Wall of Respect organized in Chicago by the Organization of Black American Culture. They, using visual art, had a tremendous and long lasting effect on the issue they protested, where a wall became a mural which was created by artists and residents of the area, which depicted many Black heroes. This became a base for more [protest] developments of this kind. Such social and political protests also came from individual artists and not a group or an organization per se - David Hammons used art to blatantly project his thoughts – His Injustice Case shows a captive tied to a chair, who could be a prisoner stating that America is not just in all cases, explicitly throwing light upon the injustices the country does. Also, Hammons public art work called the Higher Goals has a multitude of shiny bottle caps on telephone poles and a basketball at the top of the poles, explaining street life in terms of the youth – the lack of an education and what basketball has been doing to the Black community of his time.

Such protests using visual art gradually developed in various parts of the world, for it seemed not only a medium to vent frustrations but also a very attractive means to attract public attention for change. In Britain, Rasheed Araeen [1935] protested the differences in culture that had seeped into the fabric of British society. Voicing his opinion [in the seventies] that African and Asian and Latin American artists were not being represented by British cultural organizations and institutions, he curated exhibitions and used writing as a means to project this. His art works spoke blatantly of the discriminations that occurred in Britain, voicing for many artists who shared a similar opinion as him. What artists like Rasheed have done to contribute to the demand for change using art saw the start of using it from a whole new dimension – both in intellectually and creatively. It taught that art becomes whole when an idea is present to prop it up, for without an idea it loses its strength for which it has set out to do. Coupled with using it for protests, creativity thus found a new sphere of being. And behind the thought of making art a modern medium to protest, the use of an idea came to the forefront.