- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- What's Behind This Orange Facade!

- “First you are drawn in by something akin to beauty and then you feel the despair, the cruelty.”

- Art as an Effective Tool against Socio-Political Injustice

- Outlining the Language of Dissent

- Modern Protest Art

- Painting as Social Protest by Indian artists of 1960-s

- Awakening, Resistance and Inversion: Art for Change

- Dadaism

- Peredvizhniki

- A Protected Secret of Contemporary World Art: Japanese Protest Art of 1950s to Early 1970s

- Protest Art from the MENA Countries

- Writing as Transgression: Two Decades of Graffiti in New York Subways

- Goya: An Act of Faith

- Transgressions and Revelations: Frida Kahlo

- The Art of Resistance: The Works of Jane Alexander

- Larissa Sansour: Born to protest?!

- ‘Banksy’: Stencilised Protests

- Journey to the Heart of Islam

- Seven Indian Painters At the Peabody Essex Museum

- Art Chennai 2012 - A Curtain Raiser

- Art Dubai Launches Sixth Edition

- "Torture is Not Art, Nor is Culture" AnimaNaturalis

- The ŠKODA Prize for Indian Contemporary Art 2011

- A(f)Fair of Art: Hope and Despair

- Cross Cultural Encounters

- Style Redefined-The Mercedes-Benz Museum

- Soviet Posters: From the October Revolution to the Second World War

- Masterworks: Jewels of the Collection at the Rubin Museum of Art

- The Mysterious Antonio Stellatelli and His Collections

- Random Strokes

- A ‘Rare’fied Sense of Being Top-Heavy

- The Red-Tape Noose Around India's Art Market

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata, January – February 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Art Bengaluru

- Delhi Dias

- Musings from Chennai

- Preview, February, 2012 – March, 2012

- In the News-February 2012

- Cover

ART news & views

Larissa Sansour: Born to protest?!

Issue No: 26 Month: 3 Year: 2012

Based on a conversation with the artist

by Franck Barthelemy

The first time I heard about Larissa Sansour's work is at the occasion of the Elysées Lacoste Award 2011. In a few days, bloggers and journalists rightly reported her eviction from the short listed nominees. How could an artist be censored in the 21st century Europe? She must be saying something different, I told myself. I searched extensively and naturally found Larissa's website. There, I discovered an amazingly emotionally and politically charged art. Larissa had something to say about her country, Palestine.

Larissa was born in Jerusalem, the city of the religions of the book, in 1973, in a very politically committed family. She grew up in Bethlehem where her father, a mathematician trained in Moscow, was requested by the Vatican to set up a university, the first one to be established in the West Bank. Throughout her childhood, Larissa and her siblings lived in a house where politicians and diplomats used to come, and argue, regularly. In the early 90s, she went to study in the UK with the full support of her family. She was rebellious and fed up with politics, fed up of living in a country at constant war. She started studying fine art and got into it more and more. In London, Baltimore, Copenhagen, she developed a style deeply rooted in a fictional narrative universe.

In 2003, Larissa Sansour closed a chapter of her life and felt the necessity to come back to reality. Her family was trapped in Bethlehem. She was anxiously following the intifada on TV and at the same time was getting news and images from the trapped friends. Highly frustrated, she noticed a huge discrepancy between the broadcast 'manipulated' news and the ground reality. She thought the situation was 'calling for a change, for people to do something about it'. She wanted to 'show the reality' and obviously to protest and shout about the ignorance of the majority. She wanted 'to bring an alternative view' of the conflict.

From hours of footage collected from friends in the West Bank, Larissa put together a six-minute video, Tank (2003) about the Bethlehem siege. Tank shows a group of peace activists trying to stop a tank. It is a blunt video, the images are not edited but the monotonous background music pulls the viewers attention on the images. The tank demonstrates its force and points the gun towards one of the activist's head. The activist does not move. Minutes later, the gun goes down and the tank backtracks. Larissa's effort to document an on-going conflict and at the same time the destruction of her home town, Bethlehem, was warmly welcomed in Copenhagen where she showed the video for the first time.

And for the first time in her life, she experienced the force of lobbies supporting the Israeli authorities. It was always subtle, never direct. Q&As were published. Galleries and museums were put under pressure. She was initially very angry and scared to be part of a public political conflict. She admits to 'expect it now'. If not, she wonders if her work is good enough.

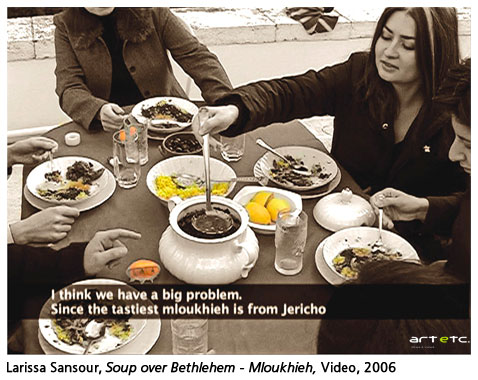

Though Larissa committed to bring out to the public images of a conflict in a very documentary way, she believed it was not enough. Lots of documentaries were shown in the early 2000s so she explored new and different ways to talk about it … or to let people talk about it. In Soup Over Bethlehem - Mloukhieh (2006), a video shot on her family's residence terrace in Bethlehem, Larissa denounced stereotypes about the conflict. Most of the Arabs involved in it, whether they like it or not, are not Muslim fanatics throwing stones. There are many families who are trying to live as normally as possible. They get together, share meal, talk about food and also about politics and the conflict. It usually starts with technical logistical questions like: is this check point open today? Can we go to this shop to get dry mloukhieh? (a delicious dish that my grandmother used to cook for me). The discussion usually ends up talking about the unfairness of being trapped and monitored. They talk about the Jewish settlements being built silently on Palestinian lands, and many other topics. Soup Over Bethlehem, improvised and unscripted, takes the viewers from fiction to reality. The casual realistic movie becomes a political statement naturally and naively. As soon as it was released, Larissa was invited to show it in many festivals around the world, including the Istanbul Biennale.

Though Larissa committed to bring out to the public images of a conflict in a very documentary way, she believed it was not enough. Lots of documentaries were shown in the early 2000s so she explored new and different ways to talk about it … or to let people talk about it. In Soup Over Bethlehem - Mloukhieh (2006), a video shot on her family's residence terrace in Bethlehem, Larissa denounced stereotypes about the conflict. Most of the Arabs involved in it, whether they like it or not, are not Muslim fanatics throwing stones. There are many families who are trying to live as normally as possible. They get together, share meal, talk about food and also about politics and the conflict. It usually starts with technical logistical questions like: is this check point open today? Can we go to this shop to get dry mloukhieh? (a delicious dish that my grandmother used to cook for me). The discussion usually ends up talking about the unfairness of being trapped and monitored. They talk about the Jewish settlements being built silently on Palestinian lands, and many other topics. Soup Over Bethlehem, improvised and unscripted, takes the viewers from fiction to reality. The casual realistic movie becomes a political statement naturally and naively. As soon as it was released, Larissa was invited to show it in many festivals around the world, including the Istanbul Biennale.

Soon after, Larissa looked at fighting another stereotype, Palestinians and Israelis cannot work together without fighting over settlements. She met with Oreet Ashery, an Israeli artist, and they conceived together a graphic novel, The Novel of Nonel and Vovel (2009): two artists got a virus and suddenly gained artistic superpowers; they decide to use it to save Palestine. With lots of humour, the super heroines address practical issues like check points, separation wall and peace in a very artistic discourse. The novel is an opportunity to think about the role of art in politics and how can artists influence. The book launch gathered many readers/viewers in London, Copenhagen and encouraged the two artists to work together again.

Soon after, Larissa looked at fighting another stereotype, Palestinians and Israelis cannot work together without fighting over settlements. She met with Oreet Ashery, an Israeli artist, and they conceived together a graphic novel, The Novel of Nonel and Vovel (2009): two artists got a virus and suddenly gained artistic superpowers; they decide to use it to save Palestine. With lots of humour, the super heroines address practical issues like check points, separation wall and peace in a very artistic discourse. The novel is an opportunity to think about the role of art in politics and how can artists influence. The book launch gathered many readers/viewers in London, Copenhagen and encouraged the two artists to work together again.

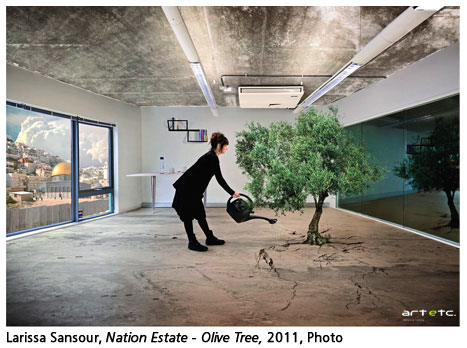

In Nation Estate (2012), Larissa's most recent work, she investigates the conflict through real estate lenses. Israel is 'eaten up' on Palestinian lands with the wall and the settlements. Israel is spreading its territories horizontally. Where are the Palestinian going to live? At some stage, they will be left with a few square meters contained within a wall. “If we cannot have land, let's go vertically”, tells Larissa. So she imagined her country in the form of a tower with a city at each floor. Second floor Souq, third floor, Jerusalem, fourth floor, Ramallah, fifth floor Bethlehem, etc. 'See how ridiculous is the situation', she adds. She imagines the olive trees of Bethlehem in air conditioned environment. She imagined the Al Aqsa mosque set right at the lift gate. From a window, we can also see the real one, outside, beyond the wall. No need to waste time at check points anymore, there is a lift to go from one city to the other. The Palestinian can finally live 'the high life', she laughs. Larissa is now preparing a movie on Nation Estate where she intends to use the latest technology in order to offer the viewer a compelling experience of the life in the tower. She recently started the production in Copenhagen and hope to be able to show it fast … money permitting. Though few sponsors are helping, she admits spending a lot of her personal money in the project and being 'broke at the moment'. No need to say that the Elysées Lacoste award could have helped.

In Nation Estate (2012), Larissa's most recent work, she investigates the conflict through real estate lenses. Israel is 'eaten up' on Palestinian lands with the wall and the settlements. Israel is spreading its territories horizontally. Where are the Palestinian going to live? At some stage, they will be left with a few square meters contained within a wall. “If we cannot have land, let's go vertically”, tells Larissa. So she imagined her country in the form of a tower with a city at each floor. Second floor Souq, third floor, Jerusalem, fourth floor, Ramallah, fifth floor Bethlehem, etc. 'See how ridiculous is the situation', she adds. She imagines the olive trees of Bethlehem in air conditioned environment. She imagined the Al Aqsa mosque set right at the lift gate. From a window, we can also see the real one, outside, beyond the wall. No need to waste time at check points anymore, there is a lift to go from one city to the other. The Palestinian can finally live 'the high life', she laughs. Larissa is now preparing a movie on Nation Estate where she intends to use the latest technology in order to offer the viewer a compelling experience of the life in the tower. She recently started the production in Copenhagen and hope to be able to show it fast … money permitting. Though few sponsors are helping, she admits spending a lot of her personal money in the project and being 'broke at the moment'. No need to say that the Elysées Lacoste award could have helped.

Larissa Sansour had made many more works and projects than the four discussed here. She constantly explores the Palestinian culture through political and/or activist's lenses. She is proud to be what she is and fights for her ideals though she is conscious she can only give exposure to current issues. In a way, she uses her creative energy to share with us the struggle of her country and her hopes too.

Photo Courtesy: Larissa Sansour