- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- What's Behind This Orange Facade!

- “First you are drawn in by something akin to beauty and then you feel the despair, the cruelty.”

- Art as an Effective Tool against Socio-Political Injustice

- Outlining the Language of Dissent

- Modern Protest Art

- Painting as Social Protest by Indian artists of 1960-s

- Awakening, Resistance and Inversion: Art for Change

- Dadaism

- Peredvizhniki

- A Protected Secret of Contemporary World Art: Japanese Protest Art of 1950s to Early 1970s

- Protest Art from the MENA Countries

- Writing as Transgression: Two Decades of Graffiti in New York Subways

- Goya: An Act of Faith

- Transgressions and Revelations: Frida Kahlo

- The Art of Resistance: The Works of Jane Alexander

- Larissa Sansour: Born to protest?!

- ‘Banksy’: Stencilised Protests

- Journey to the Heart of Islam

- Seven Indian Painters At the Peabody Essex Museum

- Art Chennai 2012 - A Curtain Raiser

- Art Dubai Launches Sixth Edition

- "Torture is Not Art, Nor is Culture" AnimaNaturalis

- The ŠKODA Prize for Indian Contemporary Art 2011

- A(f)Fair of Art: Hope and Despair

- Cross Cultural Encounters

- Style Redefined-The Mercedes-Benz Museum

- Soviet Posters: From the October Revolution to the Second World War

- Masterworks: Jewels of the Collection at the Rubin Museum of Art

- The Mysterious Antonio Stellatelli and His Collections

- Random Strokes

- A ‘Rare’fied Sense of Being Top-Heavy

- The Red-Tape Noose Around India's Art Market

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata, January – February 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Art Bengaluru

- Delhi Dias

- Musings from Chennai

- Preview, February, 2012 – March, 2012

- In the News-February 2012

- Cover

ART news & views

Dadaism

Issue No: 26 Month: 3 Year: 2012

by Uma Prakash

"Dada is a state of mind...Dada is artistic free thinking...Dada gives itself to nothing..." So is Dada defined by André Breton.

World War I fractured the order and sprit of the world. The reaction was a cultural movement in art that extended to literature (mainly poetry), theatre and graphic design called Dadism. The movement was, among other things, a protest against the barbarism of the war. Dadism was an eclectic freedom to experiment. Running from the destruction of war the artist turned to art. They seeked an art form that would save the world from the madness of annihilation brought about by the war.

The movement was anti art and establishment. It allowed the viewer the freedom of finding their own interpretations and the art did not have to appeal to the viewer’s senses. It could also repulse him. A new form of art was born that is evident even today in the cutting age works of the contemporary artist. Everything for which art stood, Dada represented the opposite. Where art was concerned with traditional aesthetics, Dada ignored aesthetics. If art was to appeal to sensibilities, Dada was intended to offend. Through their rejection of traditional culture and aesthetics, the Dadaists hoped to destroy traditional culture and aesthetics.

Idealism was replaced by Dadism as the artists expressed their disillusion of mankind at war. The destruction of war left the world bewildered as people watched their world disintegrate in front of their own eyes.

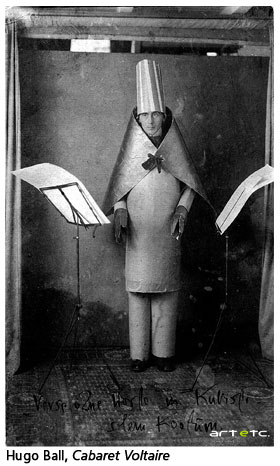

Although there were shadows of Expressionism, Cubism, and Futurism in Dadism a completely new language in art was born. The origins of the Dada movement can be traced in the opening of the Cabaret Voltaire by Hugo Ball in Zurich in 1916 with his companion Emmy Hennings. It turned out to be a cabaret reflecting artistic and political principles. Others who joined in were Marcel Janco, Richard Huelsenbeck, Tristan Tzara, and Jean Arp. The radical art movement known as Dada came into being with the proceedings at the cabaret. Refugees and artists (some had fought in the War) from all over Europe arrived in droves to Switzerland as it enjoyed a neutral status during World War I.

Although there were shadows of Expressionism, Cubism, and Futurism in Dadism a completely new language in art was born. The origins of the Dada movement can be traced in the opening of the Cabaret Voltaire by Hugo Ball in Zurich in 1916 with his companion Emmy Hennings. It turned out to be a cabaret reflecting artistic and political principles. Others who joined in were Marcel Janco, Richard Huelsenbeck, Tristan Tzara, and Jean Arp. The radical art movement known as Dada came into being with the proceedings at the cabaret. Refugees and artists (some had fought in the War) from all over Europe arrived in droves to Switzerland as it enjoyed a neutral status during World War I.

Cabaret Voltaire was a ground breaking event as this was the first time that a group of young artists and writers got together to create a centre for artistic entertainment. It was a liberating idea that allowed the guest artists to come and give musical performances and readings at the daily meetings. The young artists of Zurich, of diverse orientation, were all invited.

The spoken word, dance and music formed the essence of the boisterous cabaret with artists experimenting with new forms of performance, such as sound poetry. The exhibited was often frenzied and brutal. Here was a congregation of artists from every sector of the avant-garde, including Futurism's Marinetti. Rejection of existing norms lead to radical experiments and featured artists like Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Giorgio de Chirico, and Max Ernst.

On July 28, 1916, Ball read out the Dada Manifesto. In his manifesto, Ball professes the philosophy of Dada which consists of three major points, "1. Dada is international in perspective and seeks to bridge differences. 2. Dada is antagonistic toward established society in the modern avant-garde, Bohemian tradition of the épater-le-bourgeios posture, and 3. Dada is a new tendency in art that seeks to change co conventional attitudes and practices in aesthetics, society, and morality." In June, Ball had also published a journal with the same name. It featured work from artists such as the poet Guillaume Apollinaire and had a cover designed by Arp.

Hugo Ball said, "For us, art is not an end in itself ... but it is an opportunity for the true perception and criticism of the times we live in." In 1917, Tzara wrote a second Dada manifesto considered one of the most important Dada writings, which were published in 1918. Other manifestos followed. A single issue of the magazine Cabaret Voltaire was the first publication to come out of the movement.

After Hugo Ball left for Bern, Tzara began to spread Dada ideas to the French and Italian artists and was soon heralded as the Dada leader and master strategist. The Zurich Dadaists published the art and literature review 'Dada' beginning in July 1917, with five editions from Zurich and the final two from Paris.

When World War I ended in 1918, most of the Zurich Dadaists returned to their home countries, and some began Dada activities in other cities.

The movement of Dadaism in Germany was initiated by Jean Arp who created several collages that incorporated diverse coloured fragments. Arp’s "According to the Laws of Chance" challenged existing notions of art and experimented with spontaneous and seemingly irrational methods of artistic creation. This work is one of the several collages he made by scattering torn rectangular pieces of paper onto a paper support. He and other Dada artists embraced the notion of chance as a way of abandoning control-a creative process that would influence many subsequent generations of artists.

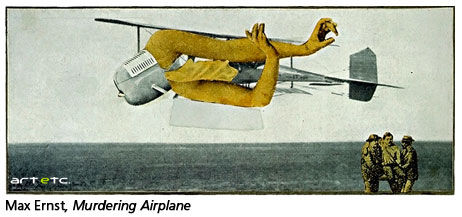

After serving in the World War I Max Ernst, along with his friend Arp became the leader of the Dada movement in Cologne. Ernst employed elements of Freud's psychology and philosophy into his art. It was the age of experiment. In 1920 he organized one of Dada’s most famous exhibitions in the conservatory of a restaurant. Entrance for the visitors was through the lavatories, and axes were provided allowing the visitors to smash the exhibits if they felt so inclined. A dramatic war related piece is Ernst’ Murdering Airplane 1920. It portrays the shell flattened landscape of northern France where he had served in the infantry. From the half aircraft, half bad angel emanates an aura of fear. Its monstrous female arms signals a dreadful horror which leaves the three tiny figures powerless figures of soldiers.

After serving in the World War I Max Ernst, along with his friend Arp became the leader of the Dada movement in Cologne. Ernst employed elements of Freud's psychology and philosophy into his art. It was the age of experiment. In 1920 he organized one of Dada’s most famous exhibitions in the conservatory of a restaurant. Entrance for the visitors was through the lavatories, and axes were provided allowing the visitors to smash the exhibits if they felt so inclined. A dramatic war related piece is Ernst’ Murdering Airplane 1920. It portrays the shell flattened landscape of northern France where he had served in the infantry. From the half aircraft, half bad angel emanates an aura of fear. Its monstrous female arms signals a dreadful horror which leaves the three tiny figures powerless figures of soldiers.

Dadism spreads to America. The New Yorkers, protesting against establishment, called their activities Dada, but they did not issue manifestos. They issued challenges to art and culture through publications such as The Blind Man, Rongwrong, and New York Dada in which they criticized the traditionalist basis for museum art. New York Dada lacked the disillusionment of European Dada and was instead driven by a sense of irony and humour.

Marcel Duchamp 1887-1968, a French immigrant who had made America his home created works that inspired artists for generations to come. In the early years Duchamp dabbled with Impressions (was very impressed by Cezanne), Fauvism and finally Cubism. However he moved on to create his own visual language which crossed all boundaries of art. He professed that art could be about an ideas instead of worldly things. A concept that is appreciated even today by the avante-garde artists.

His painting Nude Descending a Staircase (1913) was regarded scandalous. It was a revolutionary piece as it showed the human figure in motion creating a rhythm as it showed the woman descending the stairs. It went against cubism which usually appeared static. It unnerved the followers of Cubism who felt he was ridiculing the Cubic concept. He was doing something new and daring and was among the artists looking for new philosophies of art to embrace. During his travel to Paris in 1914, he purchased a bottle-rack which he converted into a work of art, which he called a readymade, becoming the first Dadaist to use the term. He completed other paintings, such as Chocolate Grinder in a style that was worlds apart from either Cubism or Abstraction, a style as crisp and precise as an architectural drawing. This work was inspired by a chocolate grinding machine that Marcel Duchamp saw in the window of a confectioner's shop in Rouen, France. The artist created the machine in a dry and impersonal painting style, like the precise mechanical drawing found in architectural plans. Duchamp was fascinated with the rotating drums of the chocolate grinder, which had a sexual connotation for him, and the machine would reappear several times in his work, most notably in the lower section of The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass) of 1915-23.

Duchamp carefully created The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even, working on the piece from 1915 to 1923. He worked on two panes of glass with materials such as lead foil, fuse wire, and dust. It combines chance procedures, plotted perspective studies, and laborious craftsmanship.

The idea came to Duchamp in 1913, and he spent much time in making notes and studies, as well as preliminary works for the piece. He had understood the creation of unique rules of physics, and myth.

In his published notes he describe that his hilarious picture is intended to depict the erotic encounter between the naked Bride who disrobes herself, in the upper panel, and her nine Bachelors depicted as empty jackets and uniforms The chocolate grinder turns squirting milk like sperm gathered timidly below signaling their frustration to the girl above. Ulf Linde created the first authorized copy of this piece in 1961. He has studied Duchamp for over half a century and has made replicas of all his major works. The latest exhibition was held recently at the Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts in collaboration with Moderna Museet.

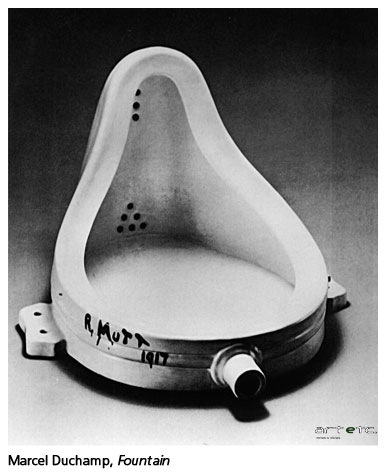

Duchamp’s most famous, and controversial ready-mades called Fountain was first introduced in April of 1917 which he entered into an art exhibition organized by

the American Society of Independent Artists, a group that Duchamp himself was a director of. Duchamp entered the readymade under the name of Richard Mutt; treating the exercise as a test for new ideas. However, because this readymade was originally manufactured to be a urinal, it was considered, by the society, to be too controversial and inappropriate and they turned it down. It was even considered immoral.

Following this action, Duchamp resigned from the society. Furthermore the urinal was flipped onto its back and called “Fountain” rather than “Urinal”.

Following this action, Duchamp resigned from the society. Furthermore the urinal was flipped onto its back and called “Fountain” rather than “Urinal”.

In 1919 he added a moustache and goatees on Mona Lisa adding attributes of a male to a famous female painting. There was sarcasm and wit in his work once again rejecting the norms of the existing society. He titled it LHOOQ in 1919 when pronounced letter by letter in French means “She’s got a hot ass”.

Bicycle Wheel was the first of a class of objects that Duchamp called his “readymades.” He created twenty-one of them, all between 1915 and 1923. The readymades are a varied collection of items, but there are several ideas that unite them. The readymades displaying the conscious effort to break every rule of the artistic tradition, in order to create a new kind of art — one that engages the mind instead of the eye, urging the observer to participate and think. The results are works of unpretentious art that refused to imitate reality. Bicycle Wheel had a lot of aesthetic appeal. Duchamp enjoyed gazing at it as it reminded him of a fireplace.

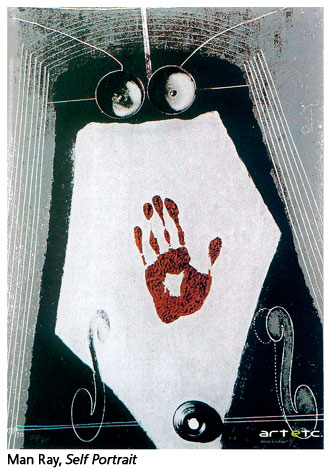

Another explosion of creativity was found in the works of Man Ray a Russian Jewish living in New York- he was a painter, sculptor, poet, photographer and object maker. He soon became the Dada photographer, who was greatly influenced by Marcel Duchamp. After meeting Duchamp, Ray moved the emphasis from the ‘retinal’ object to the ‘conceptual’ idea, along with a sense of humour that touched on the absurd. His photographs of Kiki are amazing as was his Self-Portrait, 1916, which Man Ray made at the age of 26, which is notably considered the “first proto-Dada assemblage. In his words- “On a background of black and aluminum paint I had attached two electric bells and a real push button. I had simply put my hand on the palette and transferred the paint imprint as a signature. Everyone who pushed the button was disappointed that the bell did not ring.” There are many layers in this piece. The disappointment of the viewer of pushing the button with no result restricts the viewer from entering the sanctity of Ray’s domain. The hand imprint in the shape of a nose depicts the artist’s presence.

In June 1921, Man Ray wrote his friend Tristan Tzara that “since Dada cannot live in New York,” he was planning to move to Paris, where the movement’s heart was beating stronger.

In June 1921, Man Ray wrote his friend Tristan Tzara that “since Dada cannot live in New York,” he was planning to move to Paris, where the movement’s heart was beating stronger.

Otto Dix‘s Card Playing War Criminals part flesh and part machine showed the impact of war on civilization.

In Berlin Hannah Hoch was one of the few women artist of this movement. In her Pretty Maiden 1920 she shows her understanding of the egotism of machines which she juxtaposes with the expressionist film montage, a mix of photo-engravings, machinery, and ball bearings to create her vision of the war.

The tragedies of war continue to effect artists like Pablo Picasso. His Guernica was created in response to the bombing of Guernica, Basque Country, by German and Italian warplanes at the behest of the Spanish Nationalist forces, on 26 April 1937, during the Spanish Civil War. Commissioned by the The Spanish Republican government Picasso this large mural was displayed at the Spanish display at the Paris International Exposition. Guernica shows the tragedies of war and the suffering it inflicts upon individuals, particularly innocent civilians. This work has gained a monumental status, becoming a perpetual reminder of the tragedies of war, an anti-war symbol, and an embodiment of peace is the most powerful invective against violence. It is a like a meditation on suffering.

Dadaism is responsible for many of the modern trends in contemporary art. The art of placing found objects are seen in many prominent art shows. Duchamp’s philosophy that anything could be art lives on and is prevalent in prestigious art shows all over the world. Today Dadaism is widely acclaimed by the very museums and institutions that the Dadaists protested against, and are held in high regard art critics across the world.