- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- What's Behind This Orange Facade!

- “First you are drawn in by something akin to beauty and then you feel the despair, the cruelty.”

- Art as an Effective Tool against Socio-Political Injustice

- Outlining the Language of Dissent

- Modern Protest Art

- Painting as Social Protest by Indian artists of 1960-s

- Awakening, Resistance and Inversion: Art for Change

- Dadaism

- Peredvizhniki

- A Protected Secret of Contemporary World Art: Japanese Protest Art of 1950s to Early 1970s

- Protest Art from the MENA Countries

- Writing as Transgression: Two Decades of Graffiti in New York Subways

- Goya: An Act of Faith

- Transgressions and Revelations: Frida Kahlo

- The Art of Resistance: The Works of Jane Alexander

- Larissa Sansour: Born to protest?!

- ‘Banksy’: Stencilised Protests

- Journey to the Heart of Islam

- Seven Indian Painters At the Peabody Essex Museum

- Art Chennai 2012 - A Curtain Raiser

- Art Dubai Launches Sixth Edition

- "Torture is Not Art, Nor is Culture" AnimaNaturalis

- The ŠKODA Prize for Indian Contemporary Art 2011

- A(f)Fair of Art: Hope and Despair

- Cross Cultural Encounters

- Style Redefined-The Mercedes-Benz Museum

- Soviet Posters: From the October Revolution to the Second World War

- Masterworks: Jewels of the Collection at the Rubin Museum of Art

- The Mysterious Antonio Stellatelli and His Collections

- Random Strokes

- A ‘Rare’fied Sense of Being Top-Heavy

- The Red-Tape Noose Around India's Art Market

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata, January – February 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Art Bengaluru

- Delhi Dias

- Musings from Chennai

- Preview, February, 2012 – March, 2012

- In the News-February 2012

- Cover

ART news & views

The Red-Tape Noose Around India's Art Market

Issue No: 26 Month: 3 Year: 2012

Market Insight

by AAMRA

As the dust settles down on the enthusiasm centered round the first India Art Fair held at New Delhi between January 25 and 29, it is perhaps time to look keenly at the realities of the art business in India.

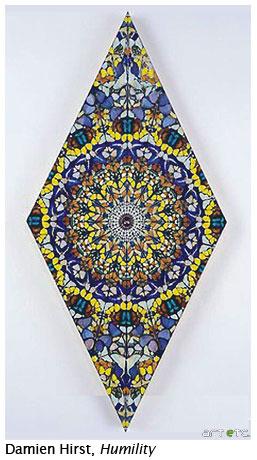

Fact is, and this is reported and corroborated across international art-media, that despite the international participation at the Fair, with galleries like White Cube ,Hauser & Wirth, as well as Damien Hirst's own Other Criteria gallery traveling to New Delhi for the first time, sales figures reported were low, and attendance, officially quoted at 80,000 was much lower than last year's 1,38,000, when it was known as the erstwhile India Art Summit and international participation was limited because of the shareholding pattern.

Fact is, and this is reported and corroborated across international art-media, that despite the international participation at the Fair, with galleries like White Cube ,Hauser & Wirth, as well as Damien Hirst's own Other Criteria gallery traveling to New Delhi for the first time, sales figures reported were low, and attendance, officially quoted at 80,000 was much lower than last year's 1,38,000, when it was known as the erstwhile India Art Summit and international participation was limited because of the shareholding pattern.

One of the reasons, ascribed by experts is that art prices in India, as in China, have declined recently after surging through the last decade, and as The Art Newspaper reports, “The market for contemporary art has been weak in India for the last six months, a decline resulting from the pre-financial-crisis bubble. And art collecting in India is still nascent.”

But the main reason behind the inertia in the growth of the art-market in India actually lies in the notorious Indian bureaucracy and its equally notorious practice of red-tapism. Unlike China, India does not actually have a clear policy to deal with art. Art in this country is regarded as a value-added luxury, and like gold or real-estate is highly taxable. Incidentally, the taxing structure in India is one of the worst in the world and Indians pay the highest taxes.

Now that the same levy-tax-duty-handling mammoth has affected one of India's first international art events, this issue is being focused upon by the international art-media. As The Guardian's Jason Burke, commenting on the slow-growth rate of the Indian art market writes, “One problem remains India's notorious bureaucracy. Many exhibitors (at the India Art Fair) had brought works only to show rather than sell, to avoid risk paying punitive duties. Others complained that works had been damaged by customs officers.”

A better understanding of how the Indian bureaucracy functions when it comes to promoting the art market is given by Artinfo.com's Shane Ferro, “The biggest obstacle to India's art market growth is its own government. Art commerce is hampered by the notorious red tape of India's sprawling state. Art is a heavily taxed luxury in the country. Take the case of India Art Fair…: While it was granted "museum status" for the first time this year, allowing it a reprieve from some of the duties levied in the past, Indian collectors were still hit hard if they purchased a work within the country. As a result, many galleries reported that they were trying to finalize transactions outside of the borders of India. That's fine if you are a collector who flew in from London, but more of a problem when it comes to interfacing with the local market. The administrative difficulties of the IAF drew the most criticism from international galleries this year…”

The duty structure levied at the India Art Fair is more extensively esplained by The Art Newspaper's Georgiana Adam: “Nothing is simple in India. Although the government had agreed to waive a customs levy on imports, there was still duty and 12.5% sales tax to be paid on anything bought at the fair, with the result that dealers were reserving rather than selling and concluding transactions out of the country. The organisers also had to contend with India's notoriously obstructive and lackadaisical bureaucracyfor example, the road to the fair was only paved the day before it opened.”

The waiver in customs levy at the India Art Fair was actually a one-off case, resulting from heavy lobbying. Otherwise, customs levy is a major deterrent in the import of contemporary art into India and thus discourages most galleries from holding shows of international standards. As a gallery owner in Kolkata explains, “Let's say I am importing a contemporary art-work worth one lakh rupees for an exhibition in my gallery in India. I have to pay a duty of 25 per cent of its quoted value to the government and because of its 'fragile' status, I will obviously have to also account in the high shipping charges. Now, if I do not manage to sell this piece of art, I have to ship it back. In effect, I am losing out on 45 per cent of its value, whereas under the same conditions in other countries, my forfeiture will just be the shipping and handling cost, which will probably amount to just 20 per cent of the quoted value of the artwork. In India, the import levy itself is more than that!”

And all that levy-structure is neither helping the art market in India, nor is it helping the government boost its coffers. On the other hand, big Indian galleries are finding ways to wriggle out of this price-barrier. Artinfo.com's Shane Ferro gives the example of a recent online-auction held by the Mumbai-based Saffronart. Though the conclusions may in part be hypothetical, they are by all practical purposes, highly plausible.

Ferro writes, “Saffronart (moved) into uncharted waters with its inaugural sale of Impressionist and modern art, featuring several Picassos and Vincent van Gogh's 1885 landscape L'Allée aux Deux Promeneurs, which (were expected to fetch prices upto) $800,000-1 million. Prices that high are nothing new for the auction house, which made a splash as the first Internet auctioneer to make a sale over the $1 million mark, and last July became the first auction house to receive a mobile bid of that amount. Still, the market for Western art is untested by Saffron, and the auction could go either way.

'Interestingly, though the headquarters for the auction house are in India, most of the art for its Imp-Mod sale is being stored in the U.S., will be shipped from New York, and must be paid for in U.S. dollars. Why? Saffronart did not respond to ARTINFO's request for an interview in time, but if we had to hazard a guess, we would say it probably has something to do with the tax and tariff problems that have also plagued the IAF. According to the Saffronart's own Web site, the taxes on art in India can be as much as 20-25 percent.”

Compare this beureaucratic attitude in democratic India to that in highly tight-lipped and socialist China's, which has already established itself as a major art-market mover, with Chinese auction houses posting growth-rates comparable to the duopoly of Sotheby's and Christie's. As Artinfo.com writes, “While India's overall economic growth is often compared to (if not quite as robust as) China's, there is no way that the art market can flourish like it has for its northeastern neighbor unless its government takes a similar approach to promoting it, combining state backing with some modicum of laissez fair attitude. While there are some notiorious problems with the Chinese model, it does have some strengths. On the one hand, China's government is highly restrictive of the art that can leave the country, and has all but banned Western collectors from the government-subsidized auction houses in Beijing, but it more than makes up for that by promoting art collecting among its own citizens (Poly and Guardian are doing just fine without Western money). However, even if they weren't, access to the Western art market is just a short flight away in Hong Kong, where there are few taxes or regulations and the bastions of art capitalism flourish: Christie's and Sotheby's do a brisk business, as do major gallery chains like Gagosian.”

These concerns were addressed by FICCI two years back in Kolkata at a summit dealing with Art Industry in India. The report on Art Industry in India: Policy Recommendations, dated April 2, 2010, concluded that:

• “A National Art Policy (“Policy”) to be formulated after due consultation with all industry factions/participants, with the overall objective of fostering the growth of art and promulgation of cultural ideas through artworks.

• World class Art Institutes/Centres for Excellence need to be established on a PPP basis.

• The existing provisions relating to Percent for Art in Public Places should be enforced.

• An Independent Regulatory Organisation (IRO) be set up by the Ministry of Culture with the objective to promote and ensure orderly growth of while protecting the interest of industry, artists and consumers.

• It is imperative to create state-of-the-art specialised channels for carrying fragile objects including artworks at airports, railway stations and ports to ensure safe and undamaged movement of art.

• A full expense deduction for the amount of donation made to the art sector by corporate establishments may be considered.

• To adjust for the income fluctuations that artists experience, an income averaging concept may be evolved for tax purposes in line with practices prevailing in Australia, Germany and other countries.

• Abolition of customs duty on import of artwork.

• A uniform 1% VAT on artworks across states in the country.

• A single window clearance system needs to be set-up for the art industry so that one is required to approach only one authority which in turn would internally co-ordinate amongst the different forums and the import/export of artwork is done seamlessly.”

Jawhar Sircar, Secretary, Ministry of Culture, Government of India had been present in person at that Summit, had commended the report and said, “I am very pleased to see such a systematic collation of ideas, proposals and desirables covering such a wide variety of issues pertaining to the world of art.”

The irony is, since then, not a single step has been taken to even consider those policy recommendations and red-tapes continue to stunt the growth of the Indian art market.

The promised land remains elusive as ever.