- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- What's Behind This Orange Facade!

- “First you are drawn in by something akin to beauty and then you feel the despair, the cruelty.”

- Art as an Effective Tool against Socio-Political Injustice

- Outlining the Language of Dissent

- Modern Protest Art

- Painting as Social Protest by Indian artists of 1960-s

- Awakening, Resistance and Inversion: Art for Change

- Dadaism

- Peredvizhniki

- A Protected Secret of Contemporary World Art: Japanese Protest Art of 1950s to Early 1970s

- Protest Art from the MENA Countries

- Writing as Transgression: Two Decades of Graffiti in New York Subways

- Goya: An Act of Faith

- Transgressions and Revelations: Frida Kahlo

- The Art of Resistance: The Works of Jane Alexander

- Larissa Sansour: Born to protest?!

- ‘Banksy’: Stencilised Protests

- Journey to the Heart of Islam

- Seven Indian Painters At the Peabody Essex Museum

- Art Chennai 2012 - A Curtain Raiser

- Art Dubai Launches Sixth Edition

- "Torture is Not Art, Nor is Culture" AnimaNaturalis

- The ŠKODA Prize for Indian Contemporary Art 2011

- A(f)Fair of Art: Hope and Despair

- Cross Cultural Encounters

- Style Redefined-The Mercedes-Benz Museum

- Soviet Posters: From the October Revolution to the Second World War

- Masterworks: Jewels of the Collection at the Rubin Museum of Art

- The Mysterious Antonio Stellatelli and His Collections

- Random Strokes

- A ‘Rare’fied Sense of Being Top-Heavy

- The Red-Tape Noose Around India's Art Market

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata, January – February 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Art Bengaluru

- Delhi Dias

- Musings from Chennai

- Preview, February, 2012 – March, 2012

- In the News-February 2012

- Cover

ART news & views

Transgressions and Revelations: Frida Kahlo

Issue No: 26 Month: 3 Year: 2012

by Snehal Tambulwadikar

“Feet, why do I need them if I have wings to fly?”

Frida Kahlo, where do we place her; where do we, place her; where, do we place her; where do we place, her; no odds of answer not for these are the answer itself. One cannot freeze Frida in any period, category, region or style; she is beyond nothing and everything. In a way considering Frida as a protest artist is curbing her boundless extensions, for protest is not her intention, it’s the reality of her persona that stands against the extreme myths of social. Frida’s art is based on self, it has none of the pretentions of morals, feminine, politics, social comment or any other contention one would put on art of various periods. It is as pure as the first painting ever done by mankind. The pain, rather living with pain, is synonymous to her, her art is the jouissance of her lifelong pain, both physical and mental. Her art is simply hers, like the innocent drawing of a child, who is not taken over by the burden of good and bad, and draw relentless lines, put free dabs of colours. Frida defies every aspect of living, expression, by being herself.

“I paint my own reality. The only thing I know is that I paint because I need to, and I paint whatever passes through my head without any other consideration.” - Frida Kahlo

Frida (1907-1954), was herself an active, aggressive person since her school days as she was part of the "Cachuchas", a political group that supported socialist-nationalist ideas and devoted themselves intensively to literature and mischief. During the same period, the ‘Mexican Renaissance’ movement began. In September 1925, Frida met with the accident which changed the course of her life, making her impaired and witness to endless pain for rest of her life, when she began painting seriously and which is the core of all her art. In 1927, after substantial recovery, joined the Young Communist League, as a part of which she met the artist and her husband Diego Rivera. With acquaintance of Diego, Frida showed him her work, which he encouraged saying that she was talented. Diego incorporated a portrait of Frida into his Ballad of the Revolution mural in the Ministry of Public Education. She appears in a panel he called Frida Kahlo Distributes the Weapons. Wearing a red star on her breast, she is shown as a member of the Mexican Communist Party, which she in fact joined in 1928. In 1936, the Spanish Civil War erupted. Frida and Diego worked together on behalf of the Republicans, raising money for Mexicans fighting against Franco's forces. In January of 1937, Leon Trotsky and his wife, Natalia Sedova, arrived in Mexico, where Leon had been granted political asylum, largely through Diego's intervention. Though always associated with politics of her times, Frida’s art does not portray the communist agendas, the war or any form of protest to the political on goings.

One would initially need to define protest to begin with, to converse about Frida Kahlo and her protest art. A ‘protest’ is an expression of objection, by words or by actions, to particular events, policies or situations. Protest can be smallest of emotion and the strongest of emotions, any effort to go against the prescribed. Frida, then, could be protesting on numerous levels, against death, against the idea of cerebralizing art, going ahead of the notion that art needs to be aesthetised, against the notions structure and the concepts of transgressing the structure at the same time. But Frida does not object to anything, just by accepting the realities and not adhering to any rules/methods whatsoever, she defies all. Interestingly, Frida wanted to paint for her living, though she never does paint for others in her works.

Frida’s protest against the death/pain is simply by accepting it, portraying it in the best possible way. She does not make a spectacle of her pain, she just records it, as if seeing it as that of other, seeing self as the other. One cannot really say that she detested or enjoyed it, she just experienced it. Pain, she experienced was both mental and physical, which was more annoying is difficult to say. What is very significant in art of Frida is that she is hurt, not beyond the pain. She does not give up, nor has she reached a level to overthrow/ignore, she moves ahead with all. The acceptance so obvious marks the different quality of her works. She does not get accustomed to things, rather takes every time as anew. Her problematic relation with Deigo affects her, which she openly admits. With her blunt portrayals, one does not want to sympathize with her, rather is taken aback by the rawness, reminded of one’s own. Years of struggle and freedom movements have hardly been able to free one of the limitless self restrictions. Frida has gone above the inhibitions, achieved by few.

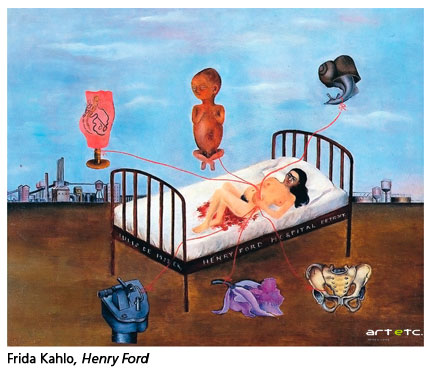

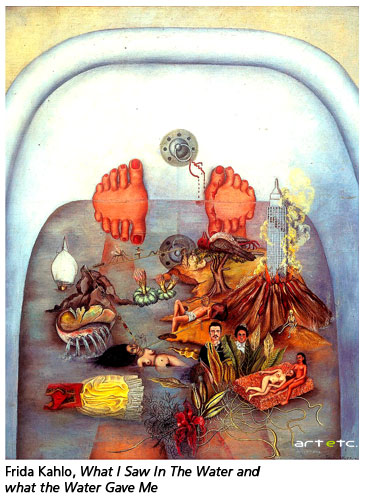

The identity that Frida has is that of Frida, she does not become a feminist. What is feminity? Something suddenly discovered in the twentieth century, that females exist and they should be treated equivalent to males, or is feminity in being a woman, with all the nuances and pleasures of the same? If feminism is recognition of women as individuals, Frida is the foremost feminist, who fêted her pain and pleasures of womanhood as an individual. Much progressive than the modernists, who represent the world to reform the world, Frida represents and projects her ‘self’, not to anyone and to everyone. System makes the truth hidden/secret, rules through sex, by making the natural urge a crime, a transgression, thus the feminity in turn becomes a transgression, which would otherwise be a normal urge. Emancipation should make woman to be human in the truest sense. Everything within her that craves assertion and activity should reach its fullest expression; all barriers should be cleared, this is the actual aim of feminist activism. But the results so far achieved have isolated her and robbed her of her ‘self’ pleasures, cerebral beings competing to equalize. External emancipation has made her an artificial being. Frida protested against these artificial ideas of womanhood, never curbing her instincts, she was not guilty of her being, never in competition with anyone, thus transgressing beyond transgression by denying the notion itself. She simply puts up her ‘self’, without any bounds, which is a protest to society which had ceased to be natural. She went ahead with what her heart said, had numerous affairs, was jealous, upset when betrayed. Her unfulfilled dream of motherhood, deterred by the accident, shattered thrice in her life, is seen in her work Henry Ford Hospital (1932), where one can see her simple womanly completion of desires being broken down. In What I Saw in Water and What the Water Gave Me (1938), Frida again challenges the physicality of pain, a simple protest against the death, with which perhaps she lived.

The identity that Frida has is that of Frida, she does not become a feminist. What is feminity? Something suddenly discovered in the twentieth century, that females exist and they should be treated equivalent to males, or is feminity in being a woman, with all the nuances and pleasures of the same? If feminism is recognition of women as individuals, Frida is the foremost feminist, who fêted her pain and pleasures of womanhood as an individual. Much progressive than the modernists, who represent the world to reform the world, Frida represents and projects her ‘self’, not to anyone and to everyone. System makes the truth hidden/secret, rules through sex, by making the natural urge a crime, a transgression, thus the feminity in turn becomes a transgression, which would otherwise be a normal urge. Emancipation should make woman to be human in the truest sense. Everything within her that craves assertion and activity should reach its fullest expression; all barriers should be cleared, this is the actual aim of feminist activism. But the results so far achieved have isolated her and robbed her of her ‘self’ pleasures, cerebral beings competing to equalize. External emancipation has made her an artificial being. Frida protested against these artificial ideas of womanhood, never curbing her instincts, she was not guilty of her being, never in competition with anyone, thus transgressing beyond transgression by denying the notion itself. She simply puts up her ‘self’, without any bounds, which is a protest to society which had ceased to be natural. She went ahead with what her heart said, had numerous affairs, was jealous, upset when betrayed. Her unfulfilled dream of motherhood, deterred by the accident, shattered thrice in her life, is seen in her work Henry Ford Hospital (1932), where one can see her simple womanly completion of desires being broken down. In What I Saw in Water and What the Water Gave Me (1938), Frida again challenges the physicality of pain, a simple protest against the death, with which perhaps she lived.

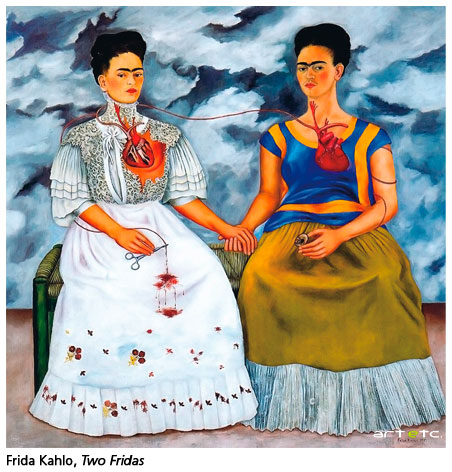

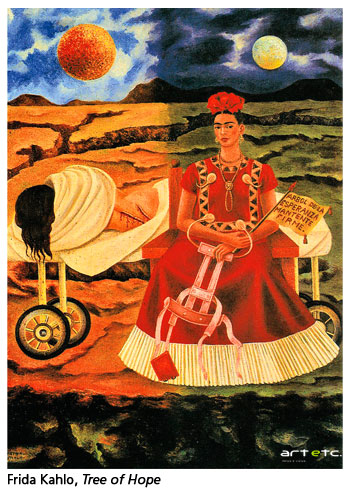

In the world of representations, the one who succeeds at representing becomes a hero. Representation undertakes to represent itself in all its elements, with images, eyes to which it is offered, the faces its makes visible, the gestures. The artist acquires the power both to act and represent at once, through the possibility of self portraiture. Self portraiture, or atleast the reading of it, reached its zenith in nineteenth century, in works of Cezanne and Van Gogh. A self portrait speaks to us in the act of the way in which the subject is the origin and end, subject and object of meaning, revealing a triumph if revelation. As Silverman suggests, a self portrait is always a portrait of oneself and other. A mirror image will establish a left-right reversal; even if the artist employs a double mirror to correct for this, the element of depth is lacking in the flatness of mirror. Yet the mirror may help in coming to terms with the appearance of what is invisible. When painting from the image in the mirror, artist takes what is typically invisible to him and brings another invisible, one that accompanies all his seeing and produces another visible which is self portrait. In the midst of this dispersion, which is simultaneously grouping and spreading, compelling from every side, is an essential void: the disappearance of its foundation- of the person it resembles and the person in whose eyes it is resemblance (Foucault). Frida, freeing the representation from what was impeding it, finally can achieve pure expression. Frida at the singular time can see the portray the visible and the invisible, as she is beyond the contentions of the self and other, she is one, that she knows, thus she can distance herself from the work and yet paint herself in Two Fridas (1939).She portrays her painful self and her ‘self’ in the work Tree of Hope (1938), when she was hospitalised and bed ridden for her eternal ailments.

In the world of representations, the one who succeeds at representing becomes a hero. Representation undertakes to represent itself in all its elements, with images, eyes to which it is offered, the faces its makes visible, the gestures. The artist acquires the power both to act and represent at once, through the possibility of self portraiture. Self portraiture, or atleast the reading of it, reached its zenith in nineteenth century, in works of Cezanne and Van Gogh. A self portrait speaks to us in the act of the way in which the subject is the origin and end, subject and object of meaning, revealing a triumph if revelation. As Silverman suggests, a self portrait is always a portrait of oneself and other. A mirror image will establish a left-right reversal; even if the artist employs a double mirror to correct for this, the element of depth is lacking in the flatness of mirror. Yet the mirror may help in coming to terms with the appearance of what is invisible. When painting from the image in the mirror, artist takes what is typically invisible to him and brings another invisible, one that accompanies all his seeing and produces another visible which is self portrait. In the midst of this dispersion, which is simultaneously grouping and spreading, compelling from every side, is an essential void: the disappearance of its foundation- of the person it resembles and the person in whose eyes it is resemblance (Foucault). Frida, freeing the representation from what was impeding it, finally can achieve pure expression. Frida at the singular time can see the portray the visible and the invisible, as she is beyond the contentions of the self and other, she is one, that she knows, thus she can distance herself from the work and yet paint herself in Two Fridas (1939).She portrays her painful self and her ‘self’ in the work Tree of Hope (1938), when she was hospitalised and bed ridden for her eternal ailments.

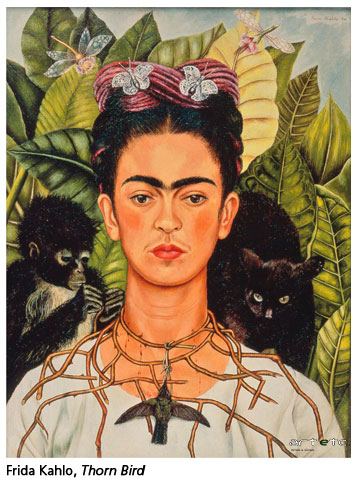

Should self portraiture and the philosophy of ‘aesthetics’ that explores it and doubles it be understood as universal fate of the visual and the painting? ‘A day will come when, by means of similitude relayed indefinitely along the length of the series, the image itself, along with the name it bears, will lose its identity’ (Foucault). In contrast with the sort of self portraiture that might epitomize the painting of the era of the man, there would be an art that practices askesis of identity, as the imagery is repeated to the point where it is emptied of meaning. Artists attempt to establish and reveal their identities, even in struggling with all the elements of otherness in the process; Frida not only transgresses her identity with her ‘selves’, but also the identity of the image itself, which as repeated is transformed through that very repetition, beginning with her first Self Portrait with a Velvet Dress (1926), Self Portrait (1930), Self Portrait with a Monkey (1938), Self Portrait with Cropped Hair (1940), Self Portrait with Necklace of Thorns (1940), The Broken Column (1944), to name a few. It is this erasure by which Frida frees herself from any of the icons of representation that haunt the visual horizons.

Should self portraiture and the philosophy of ‘aesthetics’ that explores it and doubles it be understood as universal fate of the visual and the painting? ‘A day will come when, by means of similitude relayed indefinitely along the length of the series, the image itself, along with the name it bears, will lose its identity’ (Foucault). In contrast with the sort of self portraiture that might epitomize the painting of the era of the man, there would be an art that practices askesis of identity, as the imagery is repeated to the point where it is emptied of meaning. Artists attempt to establish and reveal their identities, even in struggling with all the elements of otherness in the process; Frida not only transgresses her identity with her ‘selves’, but also the identity of the image itself, which as repeated is transformed through that very repetition, beginning with her first Self Portrait with a Velvet Dress (1926), Self Portrait (1930), Self Portrait with a Monkey (1938), Self Portrait with Cropped Hair (1940), Self Portrait with Necklace of Thorns (1940), The Broken Column (1944), to name a few. It is this erasure by which Frida frees herself from any of the icons of representation that haunt the visual horizons.

Frida protest on one more front, defying any notion of aesthetics in her art. Her art is beyond the gaze that Cezanne tries to overcome in his self, of one that impressionists tried to redefine, she is herself the subject and the spectator; she gazes into herself and the image at no one. Her works neither try to awaken your disgust, nor particularly the pleasant eye. She is not a witness to nay of the intellectual art of her times, the Dadaists, the Surrealists, neither the ideal nor the formal.

“They thought I was a Surrealist, but I wasn't. I never painted dreams. I painted my own reality.”

- Frida Kahlo

Frida could make out of her art that great philosophies take times to arrive at, the reason might be that she was so close to life that she would never require a theory to accept and anticipate the same. Rather she was not in the run to understand life, just simply taking it along as it came. Frida can thus exist in any period in history, she is beyond the phenomenology of artist.

“The most important thing for everyone in Gringolandia is to have ambition and become 'somebody,' and frankly, I don't have the least ambition to become anybody.” – Frida Kahlo

Frida Kahlo’s protest is that of a pure expression against all the theorizing of modern world. She poses a simple question, which the artists of all times have asked in undercurrents, what could be art and the expression of artist. She protests against the representation and spectatorship bounded to art, as she does not paint to show or to be seen. Frida has been able to achieve what years of woman emancipation has not achieved, liberty! Liberty to be a woman, to love, be loved, hate, desire, cry and be respected for all the same, not entangled in the competition to equality to anyone. A conception of world does not admit of the conqueror or conquered; it knows of but one great thing: to give of one’s self boundlessly, in order to find oneself richer, deeper; which Frida was able to achieve.

Bibliography:

1. Archaeologies of Vision, Gary Schapiro

2. Essays of Ema Goldman

3. Foucault and Feminism, Shane Phelan