- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- What's Behind This Orange Facade!

- “First you are drawn in by something akin to beauty and then you feel the despair, the cruelty.”

- Art as an Effective Tool against Socio-Political Injustice

- Outlining the Language of Dissent

- Modern Protest Art

- Painting as Social Protest by Indian artists of 1960-s

- Awakening, Resistance and Inversion: Art for Change

- Dadaism

- Peredvizhniki

- A Protected Secret of Contemporary World Art: Japanese Protest Art of 1950s to Early 1970s

- Protest Art from the MENA Countries

- Writing as Transgression: Two Decades of Graffiti in New York Subways

- Goya: An Act of Faith

- Transgressions and Revelations: Frida Kahlo

- The Art of Resistance: The Works of Jane Alexander

- Larissa Sansour: Born to protest?!

- ‘Banksy’: Stencilised Protests

- Journey to the Heart of Islam

- Seven Indian Painters At the Peabody Essex Museum

- Art Chennai 2012 - A Curtain Raiser

- Art Dubai Launches Sixth Edition

- "Torture is Not Art, Nor is Culture" AnimaNaturalis

- The ŠKODA Prize for Indian Contemporary Art 2011

- A(f)Fair of Art: Hope and Despair

- Cross Cultural Encounters

- Style Redefined-The Mercedes-Benz Museum

- Soviet Posters: From the October Revolution to the Second World War

- Masterworks: Jewels of the Collection at the Rubin Museum of Art

- The Mysterious Antonio Stellatelli and His Collections

- Random Strokes

- A ‘Rare’fied Sense of Being Top-Heavy

- The Red-Tape Noose Around India's Art Market

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata, January – February 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Art Bengaluru

- Delhi Dias

- Musings from Chennai

- Preview, February, 2012 – March, 2012

- In the News-February 2012

- Cover

ART news & views

The Art of Resistance: The Works of Jane Alexander

Issue No: 26 Month: 3 Year: 2012

by Sritama Halder

“The deformed and stunted relations between human beings that were created under colonialism and exacerbated under what is loosely called apartheid have their psychic representation in a deformed and stunted inner life.“ -J. M. Coetzee

Jane Alexander's works revolve around apartheid, history and identity. Under the broader umbrella of the term 'protest art' hers is that of resistance, imbued with deep political and social understanding. In 1982 she obtained her degree in Bachelor of Arts from the University of Witwatersrand. In 1988 she finished her Masters. Shifting from the suburb of Johannesburg to the urban space of Witwatersrand was a major change for her. In urban spaces, brutality was more apparent, resistance was more potent. The amount of knowledge and information and the resultant fear one is exposed to in urban spaces is much more imposing. Though she never directly contributed to the Resistance Movement, she became aware of the students' underground movements and organizations and about South Africa's political situation.

Jane Alexander's works revolve around apartheid, history and identity. Under the broader umbrella of the term 'protest art' hers is that of resistance, imbued with deep political and social understanding. In 1982 she obtained her degree in Bachelor of Arts from the University of Witwatersrand. In 1988 she finished her Masters. Shifting from the suburb of Johannesburg to the urban space of Witwatersrand was a major change for her. In urban spaces, brutality was more apparent, resistance was more potent. The amount of knowledge and information and the resultant fear one is exposed to in urban spaces is much more imposing. Though she never directly contributed to the Resistance Movement, she became aware of the students' underground movements and organizations and about South Africa's political situation.

Born in Johannesburg in 1959, she witnessed a South Africa under British colonization fractured with racial inequity, repression, violence and struggle for freedom. The decade of the 50s saw increasingly repressive laws against the black people of South Africa. This decade was marked by the Population Registration Act (1950) that categorized people into three separate racial groups- black, white and coloured. A fourth group- Asian- was added later. From 1952 the black people were required to carry passes, the absence of which meant criminal offence. Next year, the Separate Amenities Law imposed apartheid- allotting separate zones for nonwhite people in public institutions, places and transportations- sometimes denying them access to any of the above, thus confining their movement to specific areas. With laws that refused to grant the minimum human rights to the black people, resistance movements acquired momentum.

The situation worsened in the 60s. During this period, apartheid transformed into a separate development policy that divided the black population into ethnic nations with separate homelands thus excluding them from the South African politics and alienating them within their own country. The first year of the decade saw the Sharpeville massacre when during an anti-pass campaign police killed a number of campaigners. A State of Emergency was declared which continued intermittently till 1989. Many anti-apartheid organizations were denounced as illegal and resistance groups had to go underground. Many leaders of the Resistance movements, including Nelson Mandela, were arrested, brought under trial and imprisoned. The coming years were marked by excessive repression of nonwhite people, more intense activities of the Resistance Groups and numerous strikes. The tension heightened with the police firing on school children in a protest march in Soweto. A new movement called Black Consciousness became significant in the South African freedom struggle and Steve Biko, the leader of this movement was brutally tortured and murdered in police custody. The harshness, massacre and violence continued till the 90s. By the beginning of this decade the situation became more optimistic. Mandela and other leaders were released. Though there were still occasional spurts of violence, the political situation was slowly changing. In 1994 the constitution was rewritten; for the first time in the history of South Africa free general elections were held and Nelson Mandela was sworn as the President of the new nation.

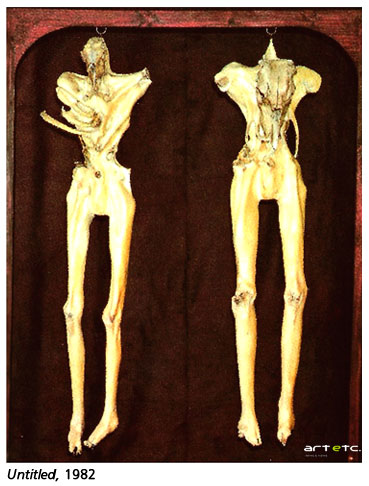

It was against this historic-political situation that Jane Alexander grew up, studied art and worked. Even though Alexander was not politically active, her works embodied the violence, threat and fear felt by a nation cowering under extreme racial aggression. Her initial pieces thus were extremely cruel. One untitled work of 1982 shows two emaciated figures with animal skulls hanging from a wooden frame. Unnaturally elongated as if by some torture equipment, these two figures probably symbolized the colonized country and its people.

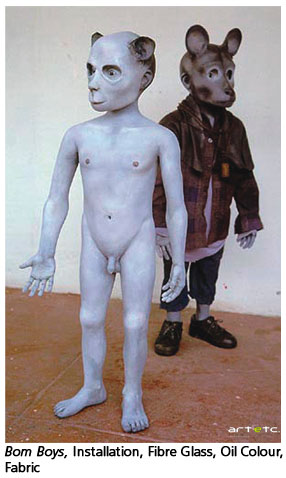

The human figures in Alexander's works are rendered with extreme realism, which makes the distortions that much more gruesome. She takes body casts and the figures are life size as well. The wounded and distorted figures disturb the sanctity of the human body and their right to completeness. The suffering of the nation is communicated through and contained by the violated human body.

A 1984 work titled Domestic Angels is a winged figure hanging from the ceiling. The small figure is upside down, but the portion from the waist to the head tries to force itself up. This upper part of the body is patchy, partially wounded and deformed as its two arms transform into wings. This distorted suspended posture of an otherwise air-borne creature tied up around the ankles reveal its vulnerability.

In the same year, the artist did a series of crawling human figures. One of them is titled Dog. It is a painted sculpture of a decapitated man with limbs missing from knee down, and yet crawling. This is again a creature fallen from the exalted identity of Man. He is lowered to the level of an animal. Wounded, unseeing and crawling he is susceptible to further brutality to his self.

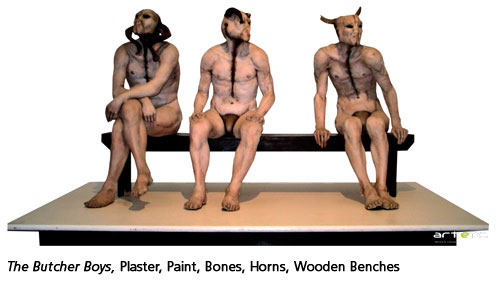

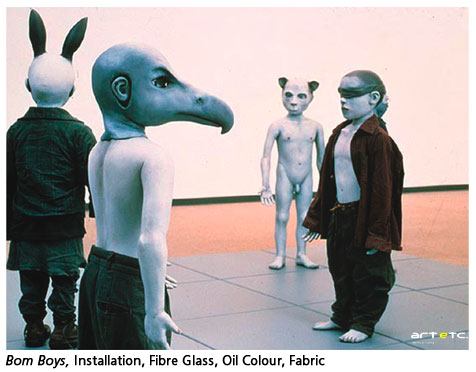

Alexander was well aware of the exceedingly disturbing elements in her works. While evaluating the works of this period she said, “I discovered that the more horrific my work, the more readily people looked at it. I began to wonder if people would respond to more restrained images. For me the work that followed was more difficult- The Butcher Boys were a radical departure from those earlier pieces- this new ones were living figures. Despite the exposed bones and so on, I was attempting to reveal aspects of violence through passive forms.” The Butcher Boys (1985/6) done while the artist was still a student of Masters, is one of her most recognized works. It shows three life-sized figures casually sitting on a bench. They have deformed human bodies with lumps of flesh hanging inertly between their legs. Gaping wounds run over their spines. Their heads are replaced by canine heads with large horns. Folds of skin loll over where the mouth should have been; instead of ears there are only dark holes. Large black beady glass eyes stare at the viewers or look away. Opaque, they cannot communicate or reciprocate. Slumped on the bench they eternally wait for some signal. Together these three creatures emanate a sense of menacing tension for they seem to occupy the real place, and yet, trapped within a bubble of nightmare, belong to a parallel frequency of time.

So far Alexander's previous works were mostly individual figures. The pain of the collective called the nation was expressed through a single body. The infinite anguish that it had condensed within it was probably the reason why those figures were so distorted, violated and wounded. The Butcher Boys tell the other side of the story. They represent the oppressors and they remind the viewers about the animal hidden under the human skin. They are the tools of the immensely powerful system against a defenseless human race.

After The Butcher Boys Alexander's works during the 90s, she became increasingly more restrained and the violence grew more subtle, to a metaphorical level. The sculpture titled Stripped (Oh Yes) Girl (1995) stands in stark contrast to the earlier pieces. She stands facing the viewer with her eyes closed and her head slightly lowered. Her shoulders slouch and the palms of her lifeless hands are spread as if in submission. Her nudity in bloodless white confronts the viewers. Her wounded abdomen and rotting flesh repel them. Hers is a dead body after post-mortem with wounds crudely sewn up. The Stripped (Oh Yes) Girl is the female Christ- Grunewald's Christ who receives the plague on the body and silently wastes away.

After The Butcher Boys Alexander's works during the 90s, she became increasingly more restrained and the violence grew more subtle, to a metaphorical level. The sculpture titled Stripped (Oh Yes) Girl (1995) stands in stark contrast to the earlier pieces. She stands facing the viewer with her eyes closed and her head slightly lowered. Her shoulders slouch and the palms of her lifeless hands are spread as if in submission. Her nudity in bloodless white confronts the viewers. Her wounded abdomen and rotting flesh repel them. Hers is a dead body after post-mortem with wounds crudely sewn up. The Stripped (Oh Yes) Girl is the female Christ- Grunewald's Christ who receives the plague on the body and silently wastes away.

In the same year Alexander did a series titled the Integration Programme. One work of this series is called Man with TV. The term 'integration' in the title points to racial integration that attempted to end the systematic discrimination based on one's racial identity in order to create equal opportunity for every citizen. It also attempted to develop culture based on multiple traditions rather than merely bringing a racial minority within the hierarchical zone of the majority. In the work, a black man, wearing his best suit, sartorially belonging to a different culture and symbol, sits rather uncomfortably on a chair. He ogles at the television set in front of him. On TV, a white man stands facing him and repeatedly adjusts his tie and hair. In this work the suit becomes the symbol of colonialism and power. The book titled Working Life: Factories, Townships, and Popular Culture on the Rand, 1886-1940, by Luli Callinicos, reveals an old photograph of a black man wearing a similar dress. Along with this the writer also gives the excerpt from a letter sent to the newspaper The Star in 1911. The letter says, 'No native should be allowed to wear ordinary European dress during working hours, and employers should combine to this end. European dress gives him an inflated sense of importance and equality.' For the black man who 'borrows' the symbol, no matter how much he tries to assimilate within the culture of the ruling race he simply cannot fit in. The white man in the TV belongs to another glittering unreality that comes down to the black man through mediation. This work is a sarcastic take on integration using the symbols of dress and technology.

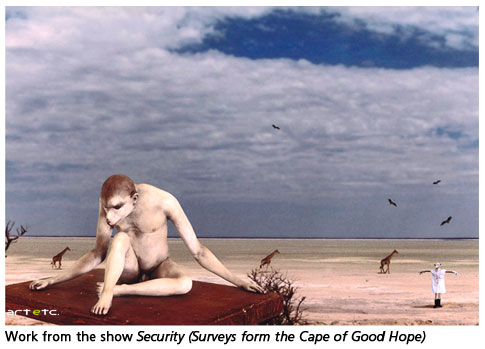

The same sarcasm is at play in her work African Adventures (1999-2002). The title suggests that the artist is looking at Africa as foreigners do. For them it is the other side of the modern urban civilization, the other side of the mirror. It is the land of national parks, safaris and adventures. Once the land of gold and diamonds that lured fortune seekers to risk their lives for the sake of the unknown, it is still the land of the exotic. Thus a continent rich with all its people, heritage, culture, history of repression and survival becomes a mere tourist spot. The work consists of thirteen figures arranged on a surface of red sand. The centre of this work is a pale skinned man with African features. Around his strapped hips farm and industrial tools and machines such as knives, sickles, toy trucks and tractors are attached which trail behind him. The figures that surround him are mutants, hybrid creatures from nightmare, immobile and isolated from each other and the viewer/s. Like all the mutant creatures in Alexander's work they act eerily like humans. The work contradicts what the title suggests. In the eyes of the outsiders Africa is the land of the exotics while the truth is exactly the opposite. It is a place where men become silent machines, half-men, half-beasts rule them and the country itself like the patch of arid red sand where no form of life can grow is bled to death.

Alexander's works almost always revolve around the situation in South Africa. But in 1995 she did a work titled Certificate of Inheritance: By the Mountains which is a comment on her personal history and identity as a Jew. She surrounds a cube with building cranes that symbolize the modern Berlin. Inside this cube is picture of the house where her father lived before his forced migration in 1936. In front of the house there is a large reptilian creature that represents the 'Jewish monster' that the Aryan German would conquer and bring peace and happiness in the world. With half-man, half bird creature looking over this whole installation from the top this arrangement this work has a fairy tale like quality where the valiant hero comes to rescue the world from evil. What connects this work with Alexander's other works is the vulnerability that identifies the Jewish people with the Black against the ugly show of power by the 'Aryan' Germans and 'white' British colonizers.

Alexander's works almost always revolve around the situation in South Africa. But in 1995 she did a work titled Certificate of Inheritance: By the Mountains which is a comment on her personal history and identity as a Jew. She surrounds a cube with building cranes that symbolize the modern Berlin. Inside this cube is picture of the house where her father lived before his forced migration in 1936. In front of the house there is a large reptilian creature that represents the 'Jewish monster' that the Aryan German would conquer and bring peace and happiness in the world. With half-man, half bird creature looking over this whole installation from the top this arrangement this work has a fairy tale like quality where the valiant hero comes to rescue the world from evil. What connects this work with Alexander's other works is the vulnerability that identifies the Jewish people with the Black against the ugly show of power by the 'Aryan' Germans and 'white' British colonizers.

The men, women, children and creatures in Jane Alexander's sculptures are life sized and they share the real space occupied by the viewer/s. Yet they have a spectral presence within that space. Exposed to everybody's eyes with all their deformities, wounds and pain they are severely closed within themselves. They are part of a living history and they occupy the space as if silently enacting small tableaux for viewers. They tell their stories but refuse pity. One may ask how relevant are these sculptures, how relevant is the past. But the past is more often never over. It decides the present and moulds the future. Once put into a broader cultural context these sculptures cease to narrate the stories of the Apartheid only. The history of repression, systematic elimination of the so called 'Other' from the mainstream, racial and religious conflicts, gender discrimination, and violence are not relegated to the past. Jane Alexander's sculptures weave the narrative of the continuum of oppressor-oppressed in evolving forms.