- Publisher's Note

- Editorial

- What's Behind This Orange Facade!

- “First you are drawn in by something akin to beauty and then you feel the despair, the cruelty.”

- Art as an Effective Tool against Socio-Political Injustice

- Outlining the Language of Dissent

- Modern Protest Art

- Painting as Social Protest by Indian artists of 1960-s

- Awakening, Resistance and Inversion: Art for Change

- Dadaism

- Peredvizhniki

- A Protected Secret of Contemporary World Art: Japanese Protest Art of 1950s to Early 1970s

- Protest Art from the MENA Countries

- Writing as Transgression: Two Decades of Graffiti in New York Subways

- Goya: An Act of Faith

- Transgressions and Revelations: Frida Kahlo

- The Art of Resistance: The Works of Jane Alexander

- Larissa Sansour: Born to protest?!

- ‘Banksy’: Stencilised Protests

- Journey to the Heart of Islam

- Seven Indian Painters At the Peabody Essex Museum

- Art Chennai 2012 - A Curtain Raiser

- Art Dubai Launches Sixth Edition

- "Torture is Not Art, Nor is Culture" AnimaNaturalis

- The ŠKODA Prize for Indian Contemporary Art 2011

- A(f)Fair of Art: Hope and Despair

- Cross Cultural Encounters

- Style Redefined-The Mercedes-Benz Museum

- Soviet Posters: From the October Revolution to the Second World War

- Masterworks: Jewels of the Collection at the Rubin Museum of Art

- The Mysterious Antonio Stellatelli and His Collections

- Random Strokes

- A ‘Rare’fied Sense of Being Top-Heavy

- The Red-Tape Noose Around India's Art Market

- What Happened and What's Forthcoming

- Art Events Kolkata, January – February 2012

- Mumbai Art Sighting

- Art Bengaluru

- Delhi Dias

- Musings from Chennai

- Preview, February, 2012 – March, 2012

- In the News-February 2012

- Cover

ART news & views

What's Behind This Orange Facade!

Issue No: 26 Month: 3 Year: 2012

Hard Talk

by Saba Gulraiz

You walls, dark and ruinous, covered with grime,

Defenceless, unpeopled and dumb!

Shall we see your revival?

Or shall you like youth just in dreams find survival? -Maironis

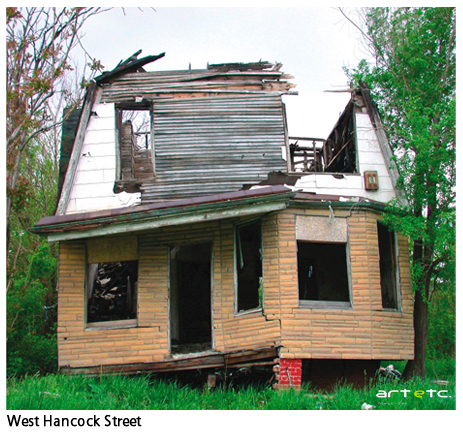

To begin with these lines of a poet of the Lithuanian Diaspora is to draw the eye towards the objects that were once called home, now crumbling and bemoaning the social and emotional isolation because their subjects have abandoned them long ago. This is the common site of most of the downtowns of the cities like Detroit. Once it was a flourishing centre of commerce and industry, now turned into a vast wasteland where your eyes can easily catch the site of thousands of such ramshackle houses that have been repudiated by their inmates for so many years. These bleak and desolated structures, reminding one of the ghetto zones of Holocaust, are the outcome of a new industrial culture that started in the late 19th century and early 20th century. First the influx of migrants seeking jobs in the newly established motor industry and then the “white flight” from these downtowns to new suburbia resulted in racial and class segregation, leaving behind the most unfortunate to face the problems caused due to weak services, high taxes, inhospitable living environs, squalor and prevalent unemployment (as the motor industry had already shifted its base to stronger areas). Such conditions contributed to the city's decay. Now over the past few decades, the motor city that gave mobility to the world is itself frozen in time and space, waiting for its revival.

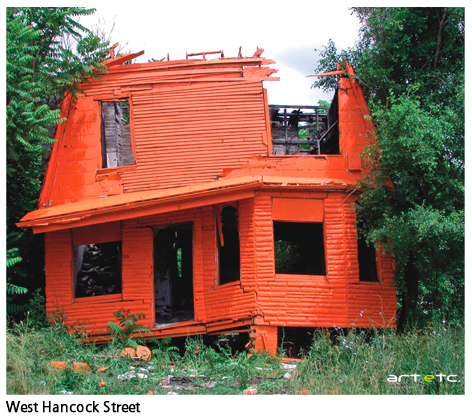

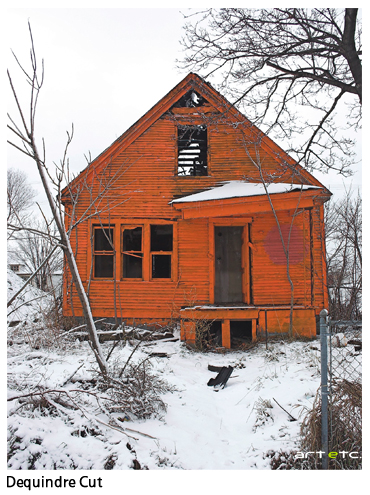

A home is a place where one can locate oneself not only physically but emotionally, psychologically and socially as well. Since Detroit has long been the city of Diasporas for whom the notion of home itself is conflicting. So, homecoming is a little possibility. Now the important question is--what are the “alter/natives''? Should these barren landscapes be brought back to life or should they simply be left for weeds and meadows? While Detroit--representative of what is happening across countries being dictated by capitalist economies--posits the complex issue of 'what is to be done of the abandoned space?' for critical discourses in a broader context, the Detroit City Council's answer to this is demolition. Years ago, they had turned these houses into objects of mass demolition by marking them with letter “D''. But this is not the one way of looking at them as these objects of demolition--when still not demolished even after so many years they had been slated for it--turned into objects of art by an anonymous gathering of Detroit artists who painted them with a coat of glistening orange. This action soon provoked a reaction from the city in the form of demolition. Their act thus constructs a new meaning of art by subverting its purpose from the forsaken object of utility into a sight specific object of art and then a possible tool of demolition.

A home is a place where one can locate oneself not only physically but emotionally, psychologically and socially as well. Since Detroit has long been the city of Diasporas for whom the notion of home itself is conflicting. So, homecoming is a little possibility. Now the important question is--what are the “alter/natives''? Should these barren landscapes be brought back to life or should they simply be left for weeds and meadows? While Detroit--representative of what is happening across countries being dictated by capitalist economies--posits the complex issue of 'what is to be done of the abandoned space?' for critical discourses in a broader context, the Detroit City Council's answer to this is demolition. Years ago, they had turned these houses into objects of mass demolition by marking them with letter “D''. But this is not the one way of looking at them as these objects of demolition--when still not demolished even after so many years they had been slated for it--turned into objects of art by an anonymous gathering of Detroit artists who painted them with a coat of glistening orange. This action soon provoked a reaction from the city in the form of demolition. Their act thus constructs a new meaning of art by subverting its purpose from the forsaken object of utility into a sight specific object of art and then a possible tool of demolition.

Object Orange is a coalescence of local artists who keep their identity anonymous; only let their first names be known as Mike, Christian, Jacque, Greg and Andy. They have to do this because their act of painting already defaced and mutilated property of nobody is considered an unlawful act for which they can be subjected to prosecution. The group's action was started way back in the year 2006 when they saw nothing was being done of thousands of dilapidated houses in the Detroit city. Since then they are on a mission of painting the city's blight orange. They just pickup their paint brush and ''Tiggerific Orange” (as they call it) and get to work in the wee hours when the city is still asleep. The object behind applying orange on the facades of abandoned houses is to exacerbate the bareness of a decaying city and thus stress the need for doing something to obliterate the ugly signs of city's blight.

Object Orange is a coalescence of local artists who keep their identity anonymous; only let their first names be known as Mike, Christian, Jacque, Greg and Andy. They have to do this because their act of painting already defaced and mutilated property of nobody is considered an unlawful act for which they can be subjected to prosecution. The group's action was started way back in the year 2006 when they saw nothing was being done of thousands of dilapidated houses in the Detroit city. Since then they are on a mission of painting the city's blight orange. They just pickup their paint brush and ''Tiggerific Orange” (as they call it) and get to work in the wee hours when the city is still asleep. The object behind applying orange on the facades of abandoned houses is to exacerbate the bareness of a decaying city and thus stress the need for doing something to obliterate the ugly signs of city's blight.

An e-conversation with three members of Object Orange--Jacque, Greg and Mike identified here as 'J', 'G', and 'M' respectively.

Saba Gulraiz: What is your object behind the 'Object Orange'?

G: The object behind 'Object Orange' is the house itself. The name was thought up as being both a catchy play on words, but also that we have turned the “house” into an “object”, which causes it to become more than a house. Instead it is transformed into an art object with meanings and implications far beyond than the original object (a house).

J: The original intent in the 'Object Orange' project was simply to make good art. Using the abandoned houses in the city of Detroit had been a goal of each of the OO member's individually long before the collaboration began. We saw the houses as material rather than just blight. We met and the project took form. It didn't fully develop however until the final collaborator, the city, entered and began demolishing the houses that we had painted. Then we had a dialogue.

SG: When did the idea that art can be used as a possible tool of demolition come upon you?

G: The idea to use the house as a tool for demolition was never a “designed” outcome. It was thought among group members that the orange paint would evoke a response, but exactly what that response was unknown. Rather the demolition was a resulting circumstance, but once realized, became an assumed outcome (i.e. - if we paint in a given neighbourhood, the house might be demolished). The fact the houses do get demolished was in my view a reaction to the art by certain viewers. The real question here then becomes “Why are they being destroyed? And what does that mean?”

J: Art has always been a tool, or vehicle, for dialogue. Working in the public sector, we hoped that our actions would provoke a response. It wasn't until the demolition happened a few times that we thought that our art could serve as a form of social reform/action in addition to aesthetic and conceptual decisions. It was a welcome surprise when the city decided to demolish our art. (I love that the city's intent was to destroy the work but in reality, they were breathing life into it). The dialogue is key, otherwise we just have ruin porn.

SG: What were the different responses you received from the people of the city over this bold amendment of painting those abandoned houses with a coat of brilliant orange?

SG: What were the different responses you received from the people of the city over this bold amendment of painting those abandoned houses with a coat of brilliant orange?

G: The responses from the people in the city were varied. But you would really have to ask them about what their reactions were. We did not perform any systematic data collection in terms of responses. Some people loved the project….some people wanted the houses torn down….some people wanted us to stop….some people wanted us to continue….In short, I would encourage you to engage them in dialogue about this project and their reaction, as this dialogue is an important component of the project.

J: Response varies depending on whom you ask. Galleries and artists love it they thought it was beautiful and conceptually engaging. Press loves it because it hits on so many levels: visual, social, cultural, and of course, we loved talking about the project so they could sense our enthusiasm. Academics love it because it is an actual manifestation of a lot of abstract concepts that interest them. But the most important reaction, that of the people in the neighbourhoods, was the most challenging. They weren't sure what to think. While they were happy that the houses were being torn down, they weren't clear about the intentions of Object Orange. It didn't matter to them that we took a photo and sold it or that we were engaging in dialogue with the city or that we were bringing national attention to a long ignored problem. What mattered to them was that the house was gone because of the destructive history and memories that were carried in those places drugs, rape, fire, death.

SG: Though orange is the colour emblematic of protection and safety, it is used by you to provoke demolition. Is the colour just an element to shock the viewers and draw their eye or it is a symbol of something else also? Please tell us about your colour concept.

G: The colour was chosen very specifically- it's called Tiggerific Orange and is part of the Disneyland paint series available at Home Depot (hence the project name Detroit. Demolition. Disneyland.). It is certainly a bright orange colour and would attract attention. The colour is referential to construction orange (often found on traffic cones or other construction related equipment). Orange is also a colour that has references to hunting (safety orange is the colour hunters wear to make sure that they don't accidentally shoot each other), but orange has also been used as a colour to symbolize revolution (Orange Revolution).

M: The colour was something we discussed quite a bit. Part of our decision-making process was the fact that our first house was part of a freeway detour. In the states, a detour sign is bright orange. It is also shaped like a house or the home plate from a baseball field. Graphically speaking it all made for a very striking symbol.

SG: These silent houses are not the mute objects of protest. Do you believe visual protest is louder than word protest?

G: I don't think that one is stronger or louder or anything than the other. Both are valid forms of communication of ideas. Our manifesto on the Detroiter.com was designed to give context to the project and serves as an additional document that highlights some of our thoughts on our actions and their meaning.

J: Did you know that Devil's Night in Detroit started out as a way of cleansing the city of abandoned houses? It started from good, not bad as the name suggests. I've heard stories from old Detroiters who said that the fire department would get emergency fire calls and then wait 30 minutes before responding because they knew that the call was for an abandoned house and they knew that those houses needed to burn. Both the parties, the arsonists and the fire department were protesting in their way, just as we paint houses orange.

SG: Your art/act besides being a statement of apathy as you had once said, is a sharp comment on the false notion of progress behind whose shining veneers are the ugly outcomes of the current global system of economy that is dictated by mere demand and supply. I would like to have your views on this.

G: First I would say that our act is a statement of anti-apathy…..the project is designed to encourage dialogue, protest, painting, or whatever. It's designed to spur people into thinking and action.

Personally, I am not anti-capitalist….I am pro-speech. I think that getting your voice heard is a duty of all citizens and that if you feel the need to express yourself by calling attention to something, then you should have at it.

M: Real estate is very interesting. A property is only worth what a buyer will pay for it. When a house in Detroit stands vacant for years there are no buyers. The house has no worth. But when we started to use those houses as artistic raw material we gave them some sort of value. We may not have increased their property value monetarily, but people were looking at them again, and also talking about them again.

SG: How do you view the question of abandoned space? What do you feel are the alternatives?

G: I think that there are some fascinating alter-narratives going on in Detroit right now that confront those issues. Design 99, Tyree Guyton and many others are working on creating alternatives to the existing norm. The exhibition Shrinking Cities that traveled internationally covered a number of possible options for urban areas where population is declining.

I think the strength of our project is that it spurs discussion without being didactic. I want people to discuss and engage, and what the outcome of that is what they are bringing to the project. I don't think the project is trying to co-opt their opinion, but rather that the art serves as a starting point for a discussion.

SG: Would you like to comment on the rhetoric of politics over this serious issue?

G: Politics, like policy, is not my end goal here. Rather, I'm looking to spur the discussion and focus the viewers' attention if only for a brief moment and get them to think.

SG: The mayor of City Council says that you are the group of law breakers and not the activists. What would you like to say on this? As your act is considered unlawful--an act of trespassing and vandalism, how do you then organize your action and evade prosecution?

G: I have no comment on the illegality of this project. Discussing it only serves to dilute my efforts to focus attention on the art.

J: If City Council followed their own ethics of morality and legality in action, the city of Detroit would be a much better place.

M: I think it is more unlawful to abandon large parts of your city and leave those areas open to blight and crime.

SG: The traffic cone orange is the signal to act. I hope by now many more hands with paint brush would have joined you in your mission to paint the city landscape orange. There are lots and lots of houses that need a coat of orange, can you tell us how many of them you have painted and how many of them have been demolished?

G: I think at last count there were 16 houses we painted, 10 of which I think were torn down. And by some estimates there are over 10,000 abandoned houses. I recognize that for me, this art project can't paint all of the houses orange. I can't, nor want, to paint them all. I think the group did a good job of highlighting the problem and bringing attention to it. For me personally, I am looking for people to focus their attention on this issue and to come up with ideas and solutions for it, perhaps on a small scale, perhaps on a grand scale. I think that would be great if there was more action in this respect.

J: I would love nothing more than to see every abandoned house in Detroit painted orange, or any other colour for that matter. Red, pink, yellow. Paint them all to bring attention to them. Pick up a brush, paint a house.

SG: What are your visions for the future of the city of Detroit and for the Object Orange Collective?

G: The conversation is going…..take part in it!

Photo Courtesy: All Photos from the Detroit. Demolition. Disneyland Series by Object Orange. Image Courtesy: Paul Kotula Projects.